When Autoimmune Disease Initiates DRY EYE

Inflammation plays a key role in the severe dry eye that can be precipitated by four common autoimmune conditions. Here’s how to make a prompt diagnosis and develop a treatment plan that’s based on the latest research.

Goal Statement:

Patients who suffer from rheumatoid arthritis Sjögren's syndrome, rosacea and systemic lupus erythematosus frequently experience dry eye. In these cases, the autoimmune disease actually targets ocular surface tissue prior to the onset of dry eye symptoms. Here, we will take a look at each of these disorders to better understand how the ocular surface responds in reaction to the inflammatory cascade as well as how to treat it.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Julie A. Rodman, O.D.

Credit Statement:

This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. COPE ID is 30433-SD. Please check your state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Joint-Sponsorship Statement:

This continuing education course is joint-sponsored by the Pennsylvania College of Optometry.

Disclosure Statement:

Dr. Rodman has no relationships to disclose.

If you see many patients with autoimmune disease, you’ve likely begun to suspect that the inflammation that affects the anterior surface of the eye often precedes the onset of dry eye and begins to initiate discomfort—even in the absence of dry eye. That’s because inflammation plays a fundamental role in the onset of dry eye disease. In fact, while the incidence of dry eye in the normal population is generally 5% to 17%, its incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, for example, is much higher (19% to 31%).1

If you see many patients with autoimmune disease, you’ve likely begun to suspect that the inflammation that affects the anterior surface of the eye often precedes the onset of dry eye and begins to initiate discomfort—even in the absence of dry eye. That’s because inflammation plays a fundamental role in the onset of dry eye disease. In fact, while the incidence of dry eye in the normal population is generally 5% to 17%, its incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, for example, is much higher (19% to 31%).1

Arthritis isn’t the only systemic autoimmune disease that leads to an increased incidence of dry eye. Patients suffering from Sjögren’s syndrome, rosacea and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) also frequently suffer from dry eye.2 In these cases, the autoimmune disease actually targets ocular surface tissue prior to the onset of dry eye symptoms. Here, we will take a look at each of these disorders to better understand how the ocular surface responds in reaction to the inflammatory cascade as well as how to treat it.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a highly inflammatory polyarthritis that can lead to joint destruction, deformity and loss of function. Additive, symmetric swelling of the joints is the hallmark of the disease. RA can cause irreversible joint damage and significant disability. It has a prevalence of 1% and occurs in twice as many women as men.3,4

The etiology of RA remains unknown, but appears to involve the combination of repeated exposure to environmental agents and genetic predisposition to autoimmune responses. The most well established genetic link is with HLA-DR4, with newer associations including polymorphisms in PTPN22 and PADI4.3,4

When severe oral and ocular symptoms are combined with ocular signs and salivary gland involvement, and often with focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, Sjögren’s syndrome may be diagnosed in conjunction with the RA. This is known as secondary Sjögren’s.5

Dryness symptoms are increased in patients with RA, increase with age, are associated with certain medications, and are associated with the severity of illness. RA contributes to sicca, as evidenced by the increase in the risk of persistent oral and ocular dryness in RA compared to normal subjects. About 25% of patients with RA will have ocular manifestations.6

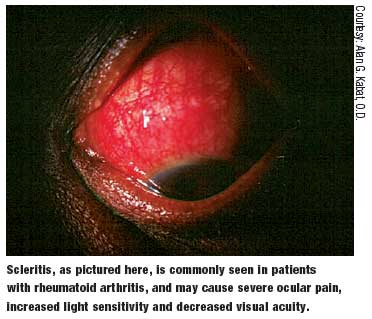

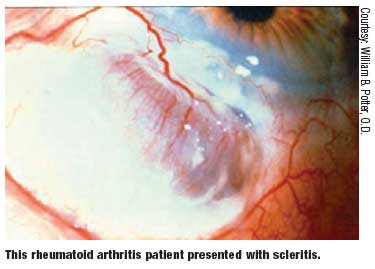

The ocular manifestations brought on by RA may include the following:6-8

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

- Scleritis

- Episcleritis

- Keratitis

- Peripheral corneal ulceration Less commonly, the following entities may also be seen in RA patients:6-8

- Choroiditis

- Retinal vasculitis

- Episcleral nodules

- Retinal detachments

- Macular edema

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is the most common ocular manifestation of RA and has a reported prevalence of 15% to 25%.6-8 Symptoms are usually prominent during the latter part of the day due to evaporation of the tear film. The lacrimal glands can be assessed with Schirmer testing or with the less invasive phenol red thread testing (Zone-Quick). Phenol testing takes less time and will adequately assess tear production.

Evidence suggests that the dry eye precipitated by RA is associated with ocular surface inflammation that may further compromise tear secretion and cause ocular surface disease and irritation symptoms. So, it is reasonable to consider anti-inflammatory therapy for patients using artificial tears who continue to have clinically detectable ocular surface disease, particularly if inflammatory signs and irritation symptoms are present.

Several agents have been identified that inhibit inflammatory mediators and mechanisms in dry eye disease. Topical corticosteroids have the most rapid onset of action. (They can be used concomitantly with cyclosporine A, a drug that may take several weeks to produce maximum therapeutic effect and up to six months for the optimum improvement.) Oral tetracyclines also may be considered for long-term therapy, as well as punctual occlusion for aqueous deficiency.9

Several agents have been identified that inhibit inflammatory mediators and mechanisms in dry eye disease. Topical corticosteroids have the most rapid onset of action. (They can be used concomitantly with cyclosporine A, a drug that may take several weeks to produce maximum therapeutic effect and up to six months for the optimum improvement.) Oral tetracyclines also may be considered for long-term therapy, as well as punctual occlusion for aqueous deficiency.9

Sjögren’s Syndrome

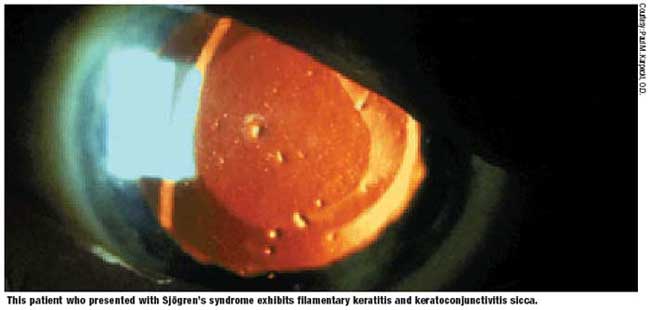

No understanding of dry eye would be complete without knowledge of Sjögren’s syndrome, which leads to a tear deficient variety of dry eye. Sjögren’s syndrome is a common, chronic autoimmune disorder described as “autoimmune epithelitis” of the exocrine glands with associated lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration of the salivary and lacrimal glands.10,11 The infiltrating lymphocytes play a major role in the glandular destruction that causes dry eye.

Sjögren’s syndrome is categorized into two groups: primary Sjögren’s (where the patients do not have any other autoimmune disease) and secondary Sjögren’s (in which the symptoms of dryness are associated with another autoimmune disorder.)1 Sjögren’s can be organ-specific or a systemic disease with synovitis, neuropathy and vasculitis.12

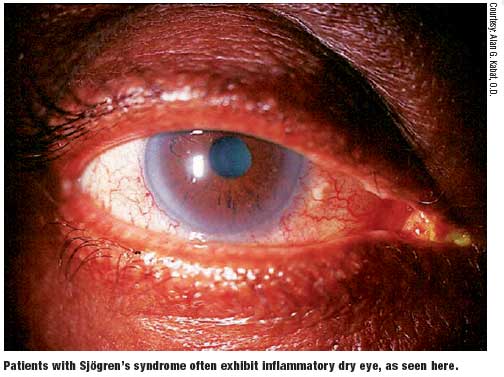

Sjögren’s syndrome may lead to chronic irritation and damage to the corneal and conjunctival epithelium leading to keratoconjunctivitis sicca, the most common ocular complication of Sjögren’s. The ocular symptoms and signs of Sjögren’s syndrome include the following:

- Foreign-body sensation

- Grittiness

- Irritation

- Photosensitivity

- Thick, rope-like secretions at the inner canthus

Complications include corneal ulceration and scarring, bacterial keratitis and eyelid infections.

Clinical assessment can be performed with the following:10

- Schirmer’s test to measure tear production.

- Tear film break-up time (TFBUT) to assess tear film stability.

- Rose bengal, fluorescein or lissamine staining to reveal corneal or conjunctival erosions.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of keratoconjunctivitis sicca has been recently recognized.13 Any cause of lacrimal gland dysfunction destabilizes the tear film and may lead to inflammation of the ocular surface. The inflammatory mechanisms are many and include decreased secretion of natural anti-inflammatory molecules such as lactoferrin, increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1B and tumor necrosis factor), increased secretion of proteolytic enzymes, and activation of cytokines and proteases (which are latent in the tears).10 The mechanisms lead to an inflammatory cascade resulting in loss of the corneal epithelial barrier function, corneal erosions and corneal surface abnormalities.

Tear Film Basics The tear film consists of three layers: mucous, aqueous and lipid. The mucin layer is the innermost layer, followed by the aqueous layer and then the outermost lipid layer. The tear fluid contains water, electrolytes, mucins, anti-microbial agents, immunoglobulins and growth factors, which form a covering and protection over the corneal surface. The aqueous layer is produced by the lacrimal glands; mucin is produced by the goblet cells of the conjunctiva; and glyco-calyx (another mucin) is produced by the corneal epithelium. The lipid layer is the outermost layer and is produced by the meibomian glands of the eyelids.10 The lipid layer lubricates the internal surface of the lids, stabilizes the tear film and reduces the evaporation of the aqueous part of the tears.29 The tear film is formed by a blink, which spreads the tears over the surface of the eye. After each blink, the tear film begins to thin. However, it still maintains a coat of aqueous over the ocular surface, until the next blink. After the next blink, a thicker tear film is reestablished and the process continues. |

Systemic therapy includes treatment of the underlying systemic disorder with steroidal and nonsteroidal agents, and cytotoxic therapy to address the extra glandular manifestations.9 Medical treatment of dry eye includes tear replacement therapy, aqueous enhancement therapy, topical anti-inflammatories and secretagogues.10,11

Recently, the following agents have been looked at more closely and are currently the subject of ongoing study:

- Sodium hyaluronate has been used as an artificial tear substitute and has shown some improvement in dry eye patients.10

- Diquafosol tetrasodium is a uridine nucleotide analog that acts as P2Y2 receptor agonist. P2Y2 belongs to the family of G-coupled protein receptors present on the ocular surface and the conjunctiva. It is a topical pharmacologic agent shown to effectively increase tear production.10,14

- Pilocarpine is a cholinergic parasympathomimetic agonist that binds to muscarinic M3 receptors and stimulates various exocrine glands, including the minor salivary glands. The benefit of pilocarpine tablets for the ocular symptoms of Sjögrens has been established.10

- Cevimeline is an acetylcholine analogue with high affinity for the muscarinic M3 receptors of the lacrimal gland epithelium. It has been shown to increase tear secretion in experimental models.10

Anti-inflammatory agents that have been used for the treatment of dry eye include topical corticosteroids, NSAIDs and cyclosporine A. Surgical treatments include punctal occlusion, tarsorrhaphy and botulinum-toxin induced ptosis.11 Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents have not shown clinical efficacy, and larger trials need to be performed.15

Dry Eye: An Inflammatory Disease Dry eye and keratoconjunctivitis sicca are common disorders of the tear film that result from inadequate tear production, excessive tear evaporation or an abnormality in the mucin or lipid components of the tear film.2,30,31 Tear-deficient eyes result from lacrimal gland dysfunction, whereas evaporative dry eye is primarily due to meibomian gland dysfunction. Both entities may result in ocular surface damage and discomfort.1 Tear hyperosmolarity appears to be the mechanism that leads to insult, resulting from either evaporation of a reduced tear volume or an increased evaporation rate in a normal amount of tears.30 This being said, while we have long known the above to be true, newer definitions of dry eye have failed to include the possible contribution of inflammation to the development of dry eye.32 Historically, dry eye has been considered an age-related dysfunction of the lacrimal gland. Recent research, however, has led to the belief that dry eye may be a complex, inflammatory syndrome of the lacrimal gland that results from changes in the composition of the tear film.32 Changes in the tear film composition and stability from a dysfunctional lacrimal unit leads to ocular surface inflammation. Inflammation and tear film instability have been found to be present in all stages of dry eye syndrome. |

Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic, inflammatory disease of the skin that is characterized by transient or persistent facial erythema, telangiectasias, papules and pustules, usually on the central portion of the face. It affects up to 14 million people in the United States.16,17 Rosacea usually starts at the age of 20 to 30, with visible progression in the next decade of life. The full clinical presentation of rosacea typically manifests between ages 40 and 50. 18

Current Trends in Treatment Several classification modalities have been developed for dry eye. They involve differentiating between aqueous tear deficiency and evaporative dry eye.23,33 However, most cases of dry eye involve both meibomian gland dysfunction (leading to evaporation) and deficiency in the aqueous component. It is now believed that assessment disease severity plays a critical role in the development of a treatment plan.33 The recent Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) report has set forth a severity scale that should be used to aid in assessing severity of dryness and formulating an appropri ate treatment plan.33 The guidelines for treatment include: • Severity Level 1. Education and environmental changes, artificial tear substitutes (gels/ ointments) and eye lid therapy. • Severity Level 2. If level 1 measures fail, then include: anti-inflammatories (cyclosporine A, topical corticosteroids), tetracyclines (meibomianitis, rosacea), punctal plugs, secreto gogues and moisture chamber spectacles. • Severity Level 3. If level 2 measures fail, then include: serum, contact lenses and perma nent punctal occlusion. • Severity Level 4. If level 3 measures fail, then include: systemic anti-inflammatory agents (cyclosporine A, prednisolone, methotrexate and infliximab) and/or surgery (lid surgery, tarsor rhaphy, mucus membrane, salivary gland and amniotic membrane transplantation).23,34 There is a new interest in the use of omega-3 fatty acids to treat dry eye disease.35 These compounds are present in fish and green leafy vegetables and have anti-inflammatory proper ties. Nutritional therapy with 1g/day to 2g/day oral flaxseed oil capsules reduces ocular sur face inflammation and may relieve dry eye symptoms in Sjögren’s patients.36 AzaSite (azithromycin, Inspire Pharmaceuticals) has been presented as a new treatment for posterior blepharitis, which involves inflammation of the meibomian glands. Azasite has anti-infective and anti-inflammatory properties and penetrates ocular tissue very well. Several reports are investigating the off-label use of Azasite for the treatment of posterior blepharitis.37 |

The pathogenesis of rosacea is heterogenic and not fully understood; however, it is primarily believed to be an inflammatory disorder. The pathophysiology involves natural immunity, vascular disturbances, action of reactive oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes, UV radiation, and infectious factors. Environmental factors play a role in the course of the disease as well. Several papers have addressed the possible role of Helicobacter pylori as a causative or exacerbating agent in rosacea.16 Other studies have documented the presence of elevated concentrations of interleukin-1alpha in the tears of patients with rosacea.16,19

Rosacea is divided into four subtypes based on clinical manifestations:18

- Erythematotelangiectaticfacial redness.

- Papulopustular-persistent central facial redness with transient papules and pustules.

- Phymatous-facial skin growth/ thickening, rhinophyma.

- Ocular rosacea-eye signs and symptoms.

Ocular signs and symptoms of rosacea are common and include:

- Foreign body sensation

- Burning

- Irritation

- Tearing

- Photophobia

- Blurred vision

- Red eyes

Clinical examination will reveal the presence of scurf, telangiectatic vascular changes of the eyelid margin, decreased TFBUT, inspissated meibomian glands, conjunctival hyperemia, punctate keratopathy, corneal vascularization and ulceration. Longstanding chronic blepharitis and rosacea may lead to hypertrophy of the lid margin, scars, madarosis, trichiasis and poliosis.16

Studies cite a moderate treatment effect from oxytetracycline for ocular rosacea.16 Several other agents, including oral and topical antibiotics, are used in the management of cutaneous rosacea. These include erythromycin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, metronidazole and ampicillin.16,20

Studies cite a moderate treatment effect from oxytetracycline for ocular rosacea.16 Several other agents, including oral and topical antibiotics, are used in the management of cutaneous rosacea. These include erythromycin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, metronidazole and ampicillin.16,20

Because rosacea has an inflammatory component, anti-inflammatory agents also have been used. Topical ophthalmic steroids are reported to be effective in the prevention of recurrent corneal erosions associated with ocular rosacea when used with oral doxycycline.16,21 Topical tacrolimus—a potent inhibitor of T-cell activation and cytokine production that penetrates the skin better than cyclosporine—has been used for rosacea in two studies; however, this is not available in an ophthalmic preparation.16,22

Restasis (ophthalmic cyclosporine, Allergan) is another inhibitor of T-cell function and is indicated for the treatment of keratoconjunctivitis. It has not been specifically evaluated in ocular rosacea; however, it does have anti-inflammatory mechanisms that may be effective in treating the dry eye associated with rosacea.9,16 Restasis provides stabilization of the tear film, protection of the corneal and conjunctival cells, reduction in evaporative tear loss by the introduction of lipids, enhanced wound healing, and enhanced lubrication between the lids and ocular surface.23

Local measures, such as warm compresses and lid scrubs, are supported by some, but evidence suggests that eyelid scrubbing may promote inflammation, particularly when used without a steroid.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

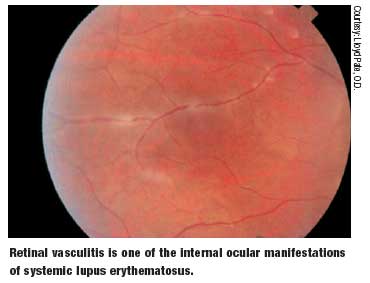

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a chronic, multisystem, autoimmune disease of unknown etiology. It is characterized by autoantibody formation and immune complex deposition that can affect almost any organ in the body.24,25 SLE will exhibit ocular manifestations in up to one third of patients.26

A diagnosis of SLE is based on the presence of four or more of the 11 features listed by the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.27 These include, but are not limited to:

- Constitutional/lymph findings, such as lymphadenopathy/splenomegaly.

- Cutaneous findings, such as malar rash, photosensitive rash, discoid lesions, alopecia and oral ulcers.

- Musculoskeletal findings, such as arthritis, myositis and fibromyalgia.

- Renal findings, such as hypertension and hematuria. • Neuropsychiatric findings, with headaches and impairment in thinking, personality changes, stroke, epilepsy, psychoses and dementia.

- Cardiopulmonary findings, with chest pain, angina, vasculitis and myocarditis.

- Gastrointestinal findings, with abdominal pain, pancreatitis, blockage or tear of the GI tract.

Remissions between periods of exacerbations are characteristic of this disease and levels of disease activity play a role in the development of ocular problems.

Remissions between periods of exacerbations are characteristic of this disease and levels of disease activity play a role in the development of ocular problems.

Ocular involvement in SLE remains a potentially blinding condition. SLE can induce ocular complications by immune complex deposition and other antibody-related mechanisms, vasculitis and thrombosis. Immune complex deposition has been found in the blood vessels of the conjunctiva, retina, choroid, sclera, ciliary body and cornea.26,28

Similar mechanisms that involve the lacrimal gland may result in secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, with resulting dry eye due to lack of adequate tear production. Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in approximately 20% of SLE patients and is indistinguishable from dry eye that is seen in patients with other autoimmune diseases.24 The symptoms range from mild (irritation and redness) to severe pain and visual loss.

Artificial tear preparations can be used to alleviate symptoms in patients with mild ocular discomfort. More extreme cases should be treated similarly to patients with secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, including the use of anti-inflammatory agents.

Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, rosacea and systemic lupus erythematosus are just a few examples of autoimmune diseases that can have severe systemic and ocular effects. But, from them, we can learn about the key role that ocular surface and lacrimal gland inflammation play in the development of dry eye and keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Dr. Rodman is an assistant professor at Nova Southeastern College of Optometry, where she is a clinical preceptor in fourth year clinic. She is also actively involved in the residency program where she serves as the residency education coordinator.

References

- Fujita M, Igarashi T, Kurai T, et al. Correlation between dry eye and rheumatoid arthritis activity. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:808-13.

- Lemp MA. Report of the National Eye Institute/Industry Workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO Journal 1995;21:221-31.

- Ngian GS. Rheumatoid arthritis. Aus Fam Phys 2010;39:626-8.

- Firestein GS. Kelley’s Textbook of heumatology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Wolfe F, Michaud K. Prevalence, risk, and risk factors for oral and ocular dryness with particular emphasis on rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheum 2008;35:1023-30.

- Patel SJ, Lundy DC. Ocular manifestations of autoimmune disease. Am Fam Phys 2002;66:991-8.

- Fuerst DJ, Tanzer DJ, Smith RE. Rheumatoid diseases. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1998;38:47-80.

- Harper SL, Foster CS. The ocular manifestations of rheumatoid disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1998;38:1-19.

- Pflugfelder SC. Antiinflammatory Therapy for Dry Eye. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137:337-42.

- Samarkos M, Moutsopoulos HM. Recent Advances in the Man agement of Ocular Complications of Sjogren’s Syndrome. Ocular Allergy 2005;5:327-32.

- Srinivasan S, Slomovic AR. Sjögren Syndrome. Compr Oph thalmol Update 2007;8:205-12.

- Kassan SS, Moutsopoulos HM: Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjogren syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1275-84.

- Yannopoulos DI, Roncin S, Lamour A, et al. Conjunctival epi thelial cells from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome inappropriately express major histocompatibility complex molecules, La(SSB) antigen, and heat-shock proteins. J Clin Immunol 1992;12:259-65.

- Jumblatt JE, Jumblatt MM. Regulation of ocular mucin secre tion by P2Y2 nucleotide receptors in rabbit and human conjunctiva. Exp Eye Res 1998;67:341-6.

- Ramos-Casals M, Tzioufas AG, Stone JH, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA 2010;304:452-60.

- Stone DU, Chodosh J. Ocular rosacea: an update on pathogen esis and therapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004;15:499-502.

- National Rosacea Society: 14 million Americans have rosacea and most of them don’t know it. Available at: www.rosacea.org (accessed January 3, 2011).

- Robak E, Kulczycka L. Rosacea. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2010;64:439-50.

- Barton K, Dagoberto CM, Nava A, et al. Inflammatory cyto kines in the tears of patients with ocular rosacea. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1868-74.

- Millikan LE: Rosacea as an inflammatory disorder: a unifying theory? Cutis 2004;73(suppl 1):5-8.

- Dursun D, Kim MC, Solomon A, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions with inhibitors of matrix metallopro teinase-9, doxycycline and corticosteroids. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:6-13.

- Bamford JTM, Elliott BA, Haller IV: Tacrolimus effect on rosa cea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:107-108.

- Lemp, MA. Advances in Understanding and Managing Dry Eye Disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146:350-5.

- Soo MPK, Chow SK, Tan CT, et al: The spectrum of ocular involvement in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without ocular symptoms. Lupus 2000;9:511-4.

- Jabs DA, Miller NR, Newman SA, et al. Optic neuropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104:564-8.

- Sivaraj RR, Durrani OM, Denniston AK, et al: Ocular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2007;46:1757-62.

- Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al: The 1982 revised criteria for classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271-7.

- Karpik AG, Schwartz MM, Dickey LE, et al. Ocular immune reactants in patients dying with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1985;35:295-312.

- Pflugfelder SC, Solomon A, Stern ME: The diagnosis and management of dry eye: a twenty-five-year review. Cornea 2000;19:644-9.

- Bron AJ, Sci FM, Tiffany JM. The Contribution of Meibomian Disease to Dry Eye. The Ocular Surface 2004;2:149-64.

- Apostol S, Filip M, Dragne C, et al. Dry eye syndrome. Etio logical and therapeutic aspects. Oftalmologia 2003;59:28-31.

- Stern ME, Beuerman RW, Fox RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: The interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea 1998;17:584-9.

- Lemp, MA, Baudouin C, Baum J, et al: The definition and clas sification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classifica tion Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop (2007). Ocular Surf 2007;5:75-92.

- Stern ME, Pflugfelder SC. Inflammation in dry eye. Ocular Surf 2004;2:124-30.

- Rosenberg ES, Asbell PA. Essential Fatty Acids in the Treat ment of Dry Eye. Ocular Surf 2010;8:18-28.

- Pinheiro MN, dos Santos PM, dos Santos RC, et al: Oral flaxseed oil (Linum usitatissimum)in the treatment for dry-eye Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2007;70:649-55.

- Luchs J. Azithromycin in DuraSite for the treatment of blephari tis. Clin Ophthalmol 2010;4:681-8.