|

What to Do When

the Patient Says They Have “Ocular Migraine”

This misleading phrase can further obscure an already tricky diagnosis. Here’s how to connect the symptoms to the source.

By Leonard Messner, OD, Lukas Rocknes, OD, Melissa Turner, OD, and Jackie Burress, OD

Jointly provided by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and the Review Education Group

Release Date: August 15, 2023

Expiration Date: August 15, 2026

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: two hours

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in dealing with the visual symptoms of a patient's headaches.

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, participants should be better able to:

Recognize the pathophysiology and presentation of “ocular migraines.”

Evaluate and appropriately classify migraines.

Educate patients on potential migraine triggers.

Manage this condition and determine when referral is needed.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: PIM requires faculty, planners and others in control of educational content to disclose all their financial relationships with ineligible companies. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted and mitigated according to PIM policy. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality, accredited CE activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in health care and not a specific proprietary business interest of an ineligible company.

Those involved reported the following relevant financial relationships with ineligible entities related to the educational content of this CE activity: Faculty - Drs. Messner, Rockne, Turner and Burress have nothing to disclose. Planners and Editorial Staff - PIM has nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group has nothing to disclose.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by PIM and the Review Education Group. PIM is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education and the American Nurses Credentialing Center to provide CE for the healthcare team. PIM is accredited by COPE to provide CE to optometrists.

Credit Statement: This course is COPE-approved for two hours of CE credit. Activity #126497 and course ID 85671-NO. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use: This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. The planners of this activity do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the planners. Refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications and warnings.

Disclaimer: Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient’s condition(s) and possible contraindications and/or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

|

Migraine aura often includes a scintillating, or fortification, scotoma. Often, the central scotoma is bordered by a crescent of shimmering zigzags. Photo: George Banyas, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

A Google search of the term “ocular migraine” yields north of four million results, an impressive level of popularity for a term that is not a true diagnosis and has in fact fallen out of favor with headache specialists. Ocular migraine is a common misnomer often used synonymously to describe migraine aura with headache, migraine aura without headache, retinal migraine or ophthalmoplegic migraine. Each of these diagnoses has distinguishing characteristics outlined by the International Headache Society (IHS) in the latest International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3). Rather than using the term ocular migraine diagnostically, it is helpful to think of ocular migraine as an umbrella term encompassing those various entities.

Accurate diagnosis is important, as use of these terms interchangeably, under the guise of ocular migraine, may lead to inappropriate workup and management. Note that ocular migraines are a diagnosis of exclusion. It is important to rule out substantial ocular pathology and/or systemic causes of the visual disturbances to ensure no further testing or referral is needed for your patient.

How are Migraines Classified?

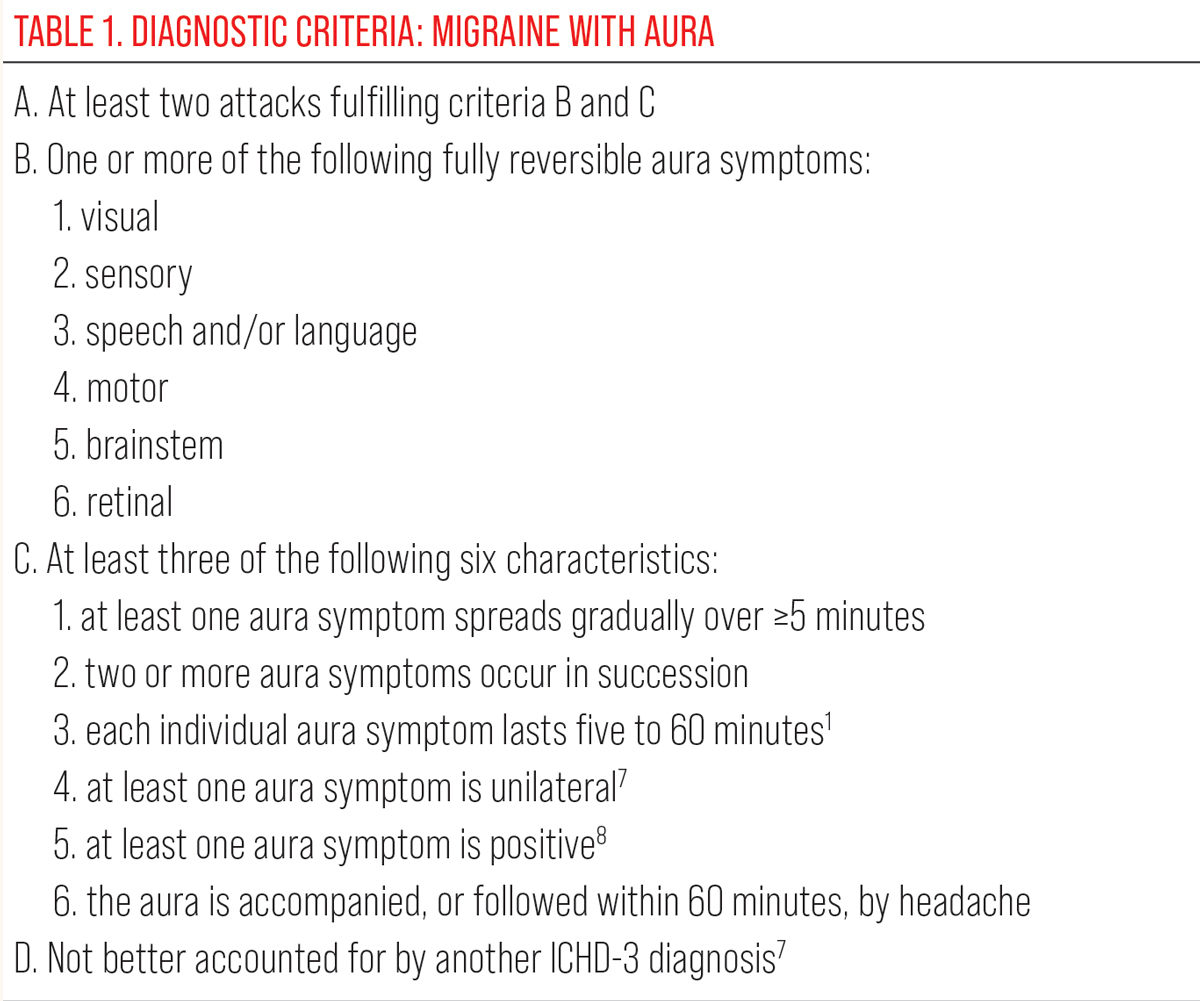

The ICHD-3 provides the classification system of migraine headaches and identifies what features a migraine must demonstrate to fit within a certain category. Management and care of these patients depends on a clear understanding of these classifications.

Migraine aura with headache. Formerly known as classic migraine, this form accounts for approximately one-third of all cases.1 It is defined by brief, recurrent attacks of visual, sensory or other central nervous system symptoms (i.e., auras) that are bilateral in nature and develop gradually, with subsequent headache and associated migraine symptoms.

Visual aura symptoms (VAS) are overwhelmingly the most common of these auras, with one study demonstrating such phenomena occurring in 98% of those with migraine aura. Less common types of auras include somatosensory disturbances, dysphasia and motor and brainstem abnormalities. It is critical to note that the visual aura symptoms experienced in migraine aura are homonymous (occupy the left or right visual field) and binocular. Their binocular nature is a key distinguishing feature for a diagnosis of migraine with aura compared to the unilateral visual symptoms of retinal migraine.

Hemiplegic migraine, a rare subtype, includes familial and sporadic forms and is characterized by motor weakness accompanying the migraine with aura.2

All About AuraMigraine auras are considered to be transient visual, sensory or speech disturbances. Visual disturbances are the most likely form of disturbance, present in with 98% to 99% of migraine auras.25 Visual aura symptoms are typically bilateral, fully reversible and have a variety of presentations. Some of the most commonly described visual disturbances include flashes of light or photopsia, scintillating scotomas, blurred or “foggy” vision, jagged or wavy lines, bright spots or blind spots.25 The classic scintillating scotoma is typically a blurred scotoma of vision encircled by sparkling lights or jagged shimmering lines like heat waves over hot pavement.30 Of the wide variety of symptoms of visual auras, the symptoms can also often be categorized as positive or negative. Positive symptoms add to the visual space such as photopsia symptoms or jagged lines. Negative symptoms subtract from the visual space such as blurred or blind spots.4 Optic nerve abnormalities typically produce negative scotomas and need to be ruled out when patients experience those types of visual disturbances. Migraines may also present with a brainstem aura. This is an aura accompanied by at least two brainstem symptoms and no motor or retina symptoms. The brainstem symptoms include dysarthria, vertigo, tinnitus, hyperacusis, diplopia, ataxia and decreased consciousness.2 |

Migraine aura without headache. Previously known as acephalgic migraine, this presentation fulfills the criteria of migraine aura with headache but lacks a concomitant or succeeding headache. It is essentially a periodic neurological phenomenon occurring in isolation. As in migraine aura with headache, VAS are binocular, and its diagnosis requires comprehensive neurologic investigation to rule out thromboembolic disease of the eye or brain.

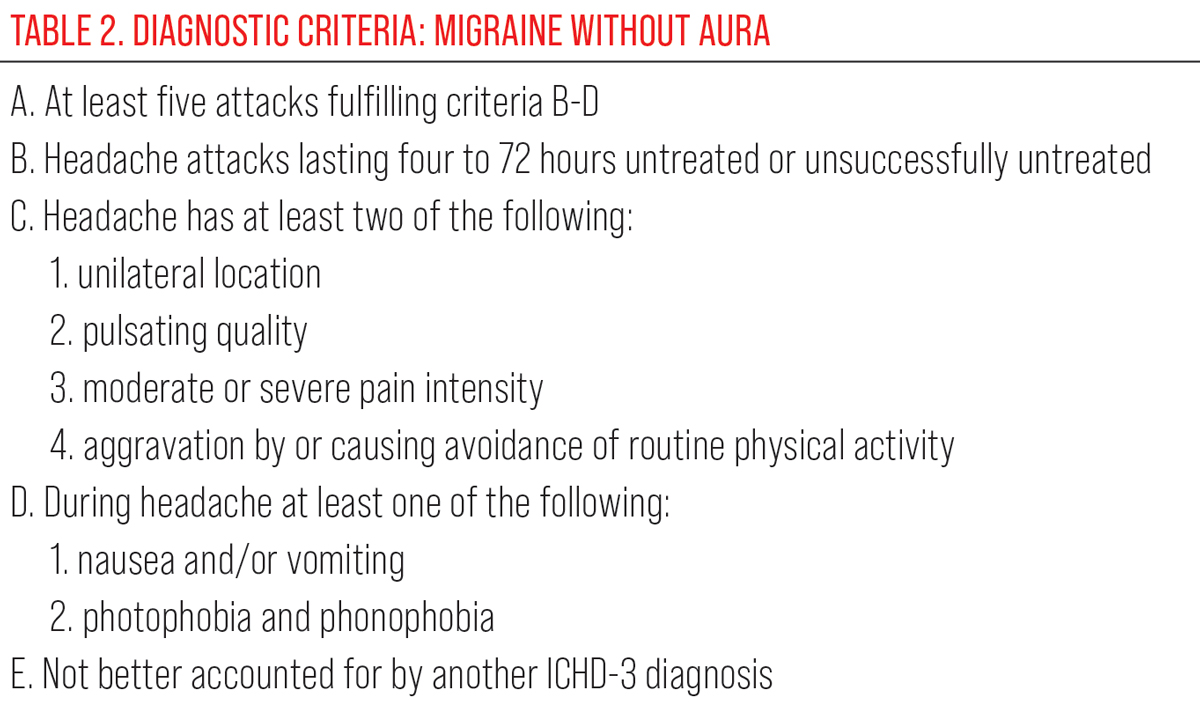

Migraine without aura. Migraines are considered to be a neurological disorder with debilitating headaches, which should be accompanied by either or both nausea and/or vomiting or light sensitivity and noise sensitivity. These severe headaches can affect each person in many different ways. Photophobia or light sensitivity may occur simultaneously to the migraine headache, but photophobia is not considered to be an aura. Additionally, 54% of migraine sufferers note blurred vision accompanying the migraine headaches.3

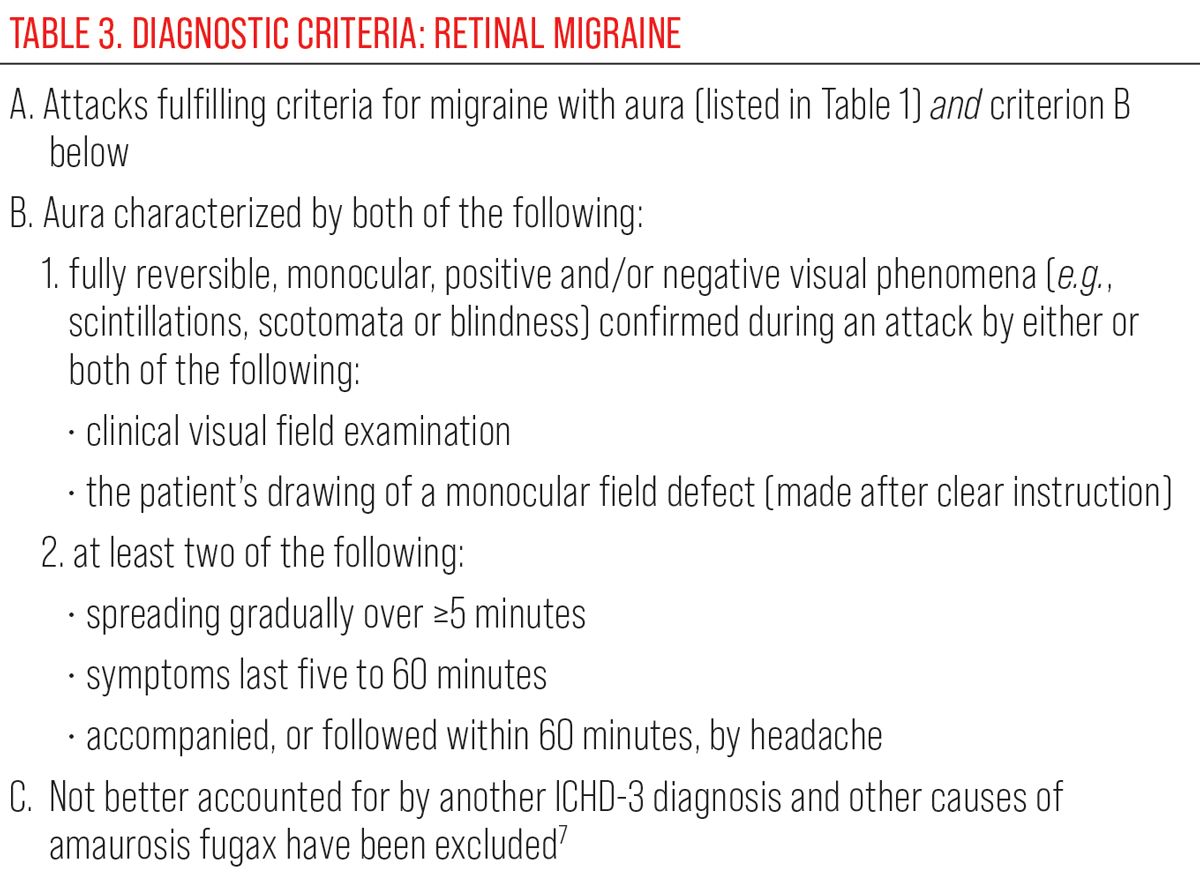

Retinal migraine. These are episodes of transient vision loss in only one eye that are followed by a headache/migraine.4,5

Retinal migraine is a diagnosis of exclusion and although the incidence is difficult to ascertain, a review done by Hill et al. showed retinal migraine (as defined in the IHS classification) to be exceedingly rare, suggesting most diagnosed cases would be more properly classified as presumed retinal vasospasm.6 The latest ICHD-3 criteria classifies retinal migraine as repeated attacks of monocular visual disturbance involving positive and/or negative visual phenomena associated with typical migraine headache. As in migraine with aura, symptoms spread gradually over minutes and are fully reversible.6-9

The vision loss can range from various types of scotomas (black, white or even shaded) to blurred vision to complete loss of vision in the affected eye.4 The most stereotypical pattern of a retinal migraine involves “patchy” areas of fading vision over the course of one minute. Then, the vision becomes further reduced one to five minutes into the event. Finally, the vision returns in the opposite pattern to which it faded.10 While this may be the typical case, episodes may last up to 60 minutes, and there have been documented cases lasting several hours.4,5 While these negative symptoms are the most common in retinal migraine, positive symptoms including flashing lights and scintillating scotomas can occur.4

Of note, the appellation “ophthalmoplegic migraine” is now known as recurrent, painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy (RPON). It has since been removed from migraine types and is now classified as a neuronitis. RPON is characterized by episodes of ipsilateral headache followed by paresis of one or more cranial nerves and is strongly associated with youthful age. Cranial nerve III is most commonly involved, followed by VI and IV, respectively.

Oculomotor palsy may occur with or without pupillary involvement. The cranial neuropathy may occur coincident with or up to 14 days after onset of headache. Ophthalmoplegia may persist for weeks to months and is typically self-limiting. In the acute phase, there is often an enhancing lesion of the involved cranial nerve on MRI.11

Presentation and Pathogenesis

The visual symptoms of these diagnoses are often what prompts patients to seek care from an eyecare provider. Although not experienced by every migraineur, migraine aura has four phases that include the following:

1. Prodrome. This phase, occurring in up to 77% of those who suffer from migraines by one account, occurs days to hours before a migraine attack.12 Fatigue, incessant yawning, food cravings and muscle stiffness are common prodromal symptoms. Activation of the hypothalamus is thought to have an intimate role in the prodromal phase of migraine.13,14

|

|

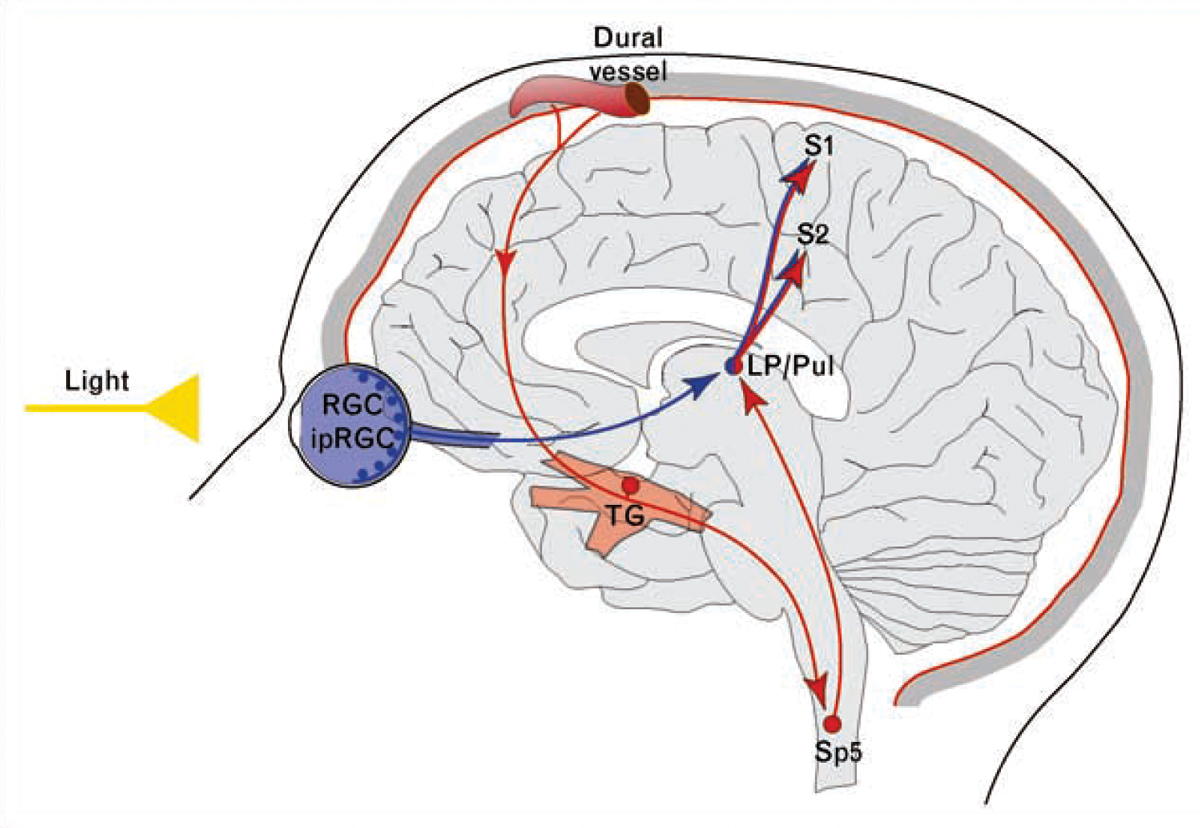

Proposed mechanism for exacerbation of migraine headache by light through convergence of the photic signals from the retina and nociceptive signals from the meninges on the same thalamic neurons that project to the somatosensory cortices. Red depicts the trigeminovascular pathway. Blue depicts the visual pathway from the retina to the posterior thalamus. ipRGCs: intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells; LP: lateral posterior nucleus; Pul: pulvinar; RGCs: retinal ganglion cells; S1: primary somatosensory cortex; S2: secondary somatosensory cortex; Sp5: spinal trigeminal nucleus; TG: trigeminal ganglion. Reprinted from Noseda R, Burstein R. Advances in understanding the mechanisms of migraine-type photophobia. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2011; 24(3):197-202. Copyright 2011, with permission from Elsevier. Click image to enlarge. |

As previously mentioned, VAS are binocular and homonymous in migraine aura (with or without headache). It is important to note that patients will often report monocular symptoms due to the common perception that the left half of the visual world is coming from the left eye and the right half of the visual field is coming from the right eye. Other non-visual auras (somatosensory, dysphasic, motor and brainstem auras) are less common than visual symptoms.

3. Headache. This will manifest as a unilateral, pulsatile pain often localizing to the frontotemporal aspect of the head and ocular area, although it can be distributed anteriorly or posteriorly in regions of the head and upper neck. Movement (e.g., standing up or walking up stairs) exacerbates head pain. Accompanying symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia will be present as the headache progresses.

4. Postdrome. Succeeding symptoms of migraine attacks include weakness, fatigue, irritability and difficulty concentrating.

Pathophysiology

The complete mechanism by which migraines arise is still not entirely understood. It was previously thought that migraine aura (with or without headache) was facilitated by changes in brain vasculature. The now outdated vascular theory of migraine suggested aura was a result of vasoconstriction and migraine headache a result of subsequent vasodilation.16 However, it is now known that vasodilation does not usually occur during migraine attacks, and vasoconstriction occurs in the late stage of migrainosus pain.12,17 Portions of the vascular theory may still hold true, but the pathophysiology is now thought to be related to activation and release of chemical mediators that lead to a cascade of neural and vascular events.12,17

There are many nociceptive structures found in the head, including the skin and associated superficial blood vessels, dura, venous sinuses, arteries and the sensory fibers of the 5th, 9th and 10th cranial nerves.17

Cortical spreading depression (CSD). Aura of migraine (specifically visual aura) is a cortical process resulting in binocular symptoms. CSD is recognized as a key neuropathogenic mechanism in the visual aura of migraine. It originates in the visual cortex as a slow-moving wave of depolarization of neurons and glial cells, which then propagates throughout the cortex at a rate of 2mm to 3mm per minute.12,17 The wave of hyperexcitability is thought to elicit positive visual symptoms (scintillations, phosphenes). It is also believed to trigger the trigeminovascular system and the resultant migraine pain due to changes in the meningeal vessels.12,17

Following the wave of hyperexcitability, areas of depressed electrical activity are thought to be responsible for the accompanying visual scotoma.15,18

Epidemiology of MigrainesMigraines are one of the most common type of headaches. In fact, 12% to 15% of people experience migraines.12 Migraines occur more often in women than men, affecting approximately 17% to 18% of women and only 6% of men.3,12 These numbers illustrate that migraines are even more prevalent than asthma and diabetes mellitus put together.3 According to the ICHD-3, migraine headaches without aura are the most common type of migraine, accounting for 80% of migraine occurrences.2,27 Migraines with typical aura and with headache account for 8% to 10% of migraines.25,27 It is also likely that there is a genetic component to migraines. It has been reported that 70% to 90% of people who suffer from migraine attacks have a family history of migraines.17 |

Trigeminovascular system (TVS). This is thought to play a role in pain and other associated symptoms of migraine. The TVS consists of small-caliber sensory neurons that originate in the trigeminal ganglion and upper cervical roots with terminals in the pial and dural blood vessels. The afferent neurons of this system aid in relaying nociceptive input from neural vessels and dura mater to the central nervous system component of the TVS. From there, release of vasoactive neuropeptides such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), neurokinin A and substance P influence responses in the brainstem and cervical spinal cord components of the TVS with further signaling to the thalamus and cortex.

Ultimately, this cascade of events leads to neurogenic inflammation, results in migraine pain and contributes to other associated symptoms (photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and vomiting).12,17-19 In addition, the anatomical network of the TVS helps explain the anterior and posterior distribution of migraine pain in regions of the head and upper neck.

Retinal migraine. The pathophysiology of retinal migraine is not fully understood. Some suggest the condition is due to reversible retinal vasospasm. Recorded observations of arterial vasospasm episodes of retinal migraine support this theory.20-23 Others believe retinal spreading depression, similar to CSD, may contribute to the underlying cause.24 It is important to note that a true retinal migraine is extraordinarily rare and that individuals must satisfy all components of the IHS criteria described earlier in this paper (Tables 1-3).

Complications of Migraines

ICHD-3 lists four potential complications for migraines: status migrainosus, persistent aura without infarction, migrainous infarction and migraine aura-triggered seizures. Status migrainosus is a migraine that lasts longer than 72 hours without resolution and is debilitating.2 Persistent aura without infarction is when the symptoms of the aura continue for one week or longer without resolution and without infarction indicated on neuroimaging. This is uncommon, but when it does occur it is typically bilateral and homonymous, and the symptoms may continue for months or years. A migrainous infarction is a migraine with aura symptoms lasting longer than an hour and an ischemic infarction shown on neuroimaging. Migraine aura-triggered seizures are seizures activated due to an aura.2

An individual who suffers from migraines with aura is at risk for certain other health issues, including an increased risk of an ischemic cerebrovascular event and atrial fibrillation.25 Patent foramen ovale is also more common in individuals who suffer from migraine with aura.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Since ischemic events are also a differential diagnosis for migraines with aura, it is important to remember some key differences between the two. Auras tend to occur progressively with worsening of symptoms, whereas ischemic events (whether a transient ischemic attack or stroke) occur suddenly. Auras also tend to have more positive photopic visual disturbances whereas ischemic events usually involve more of a dimming or loss of vision. Migraines are more likely to be associated with symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia.12

Retinal migraines may have ocular complications. They are typically vascular complications and may cause permanent loss of vision. Because of the pathophysiology of retinal migraines, blood flow may be impaired, leading to complications such as retinal artery occlusions, retinal vein occlusions or retinal hemorrhages.4

Associations and Potential Triggers

Patients susceptible to migraines of all forms, including acephalgic or retinal types, can be helped with proper education regarding migraine triggers and how to deal with those issues. Lifestyle changes or removing/avoiding possible triggers for migraines may help keep migraines away for some patients.

Stress, hypertension, hypoglycemia, menstruation, oral contraceptives, heat exhaustion and physical exertion may be potential triggers, as well as weather changes, higher altitude and dehydration.4,12 Some patients may be sensitive to certain foods, notably chocolate, aged cheeses, cured meats, wine and nuts.

Encouraging patients to pursue lifestyle changes, including drinking plenty of water, getting outdoors for fresh air, decreasing stress, a regular exercise routine, smoking cessation and avoiding alcohol (specifically red wine), may all aid in preventative therapy.17

Clinical Workup

Any complaint of visual disturbances requires a comprehensive ocular examination. Case history is an important component of the examination, including a description of the visual disturbance from the patient’s perspective and follow-up with additional questions. Is it constant or transient? How long does it last? Is it monocular or binocular? Does a headache accompany or follow the visual disturbance?

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Determining the laterality of visual symptoms in a patient presenting with visual aura is a critical first step in establishing an accurate diagnosis. If visual symptoms are binocular, migraine aura (with or without headache) becomes a viable differential diagnosis. However, particularly in patients who are older than 40 years old with complaints of an aura or visual disturbance without headache, other diagnoses must be ruled out such as transient ischemic attack (TIA), seizure and ocular pathology.17 This can become particularly challenging in patients with established vascular risk factors and/or diagnosed epilepsy. More youthful patients who have a positive past history of a migraine headache may not need any additional testing.17

Careful inquiry about the timing, duration, accompanying symptoms and history of similar episodes can assist in proper diagnosis. For example, an elderly male with ongoing visual symptoms, an abnormal neurologic exam and no prior history of similar visual episodes is suspicious for a TIA or giant cell arteritis rather than of migraine aura and should be worked up accordingly. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate the photopsia or migraine aura from that of vitreoretinal traction. A helpful technique is to instruct individuals with presumed visual aura of migraine to digitally manipulate the globe during subsequent events. If the visual phenomenon appears stable, it is in the brain. If it moves when the eye is moved, it is most likely in the eye.15

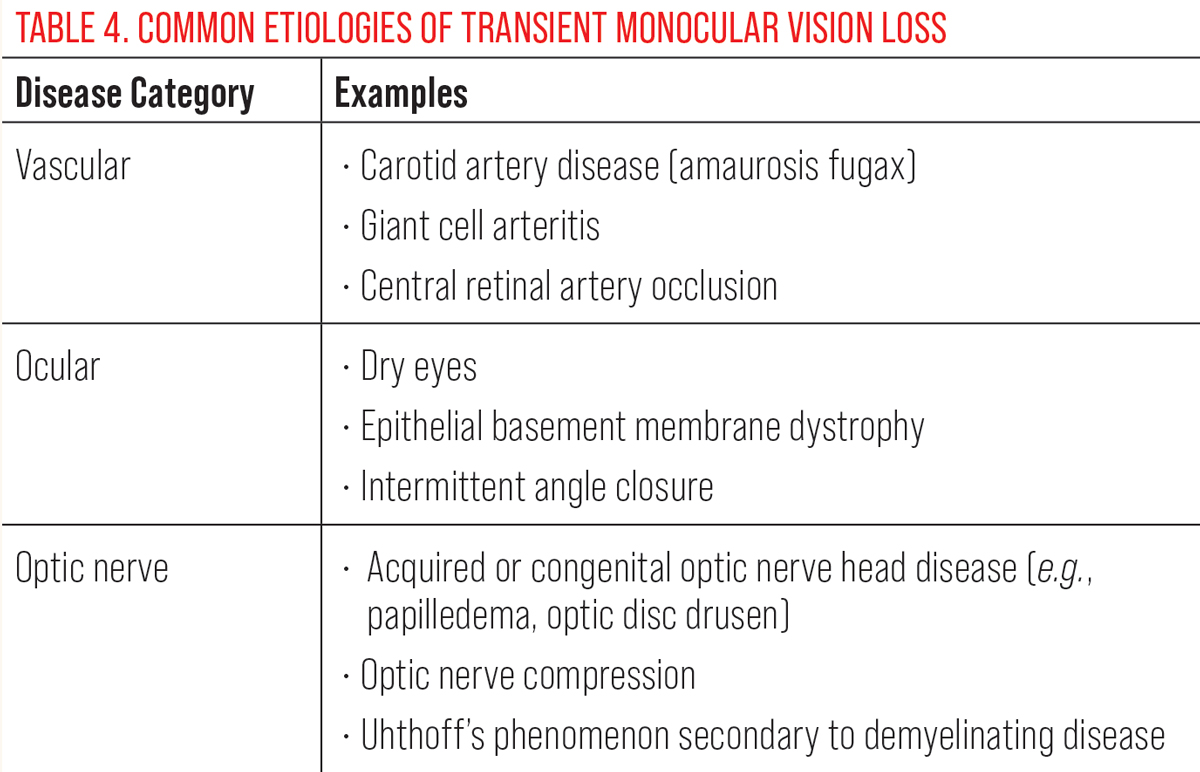

If visual complaints are monocular, etiologies resulting in transient monocular vision loss (TMVL) must be ruled out before diagnosing retinal migraine (see Table 4 for common etiologies of TMVL). These may include, among other things, amaurosis fugax, transient ischemic attacks, increased intracranial pressure, orbital apex mass, optic neuritis, carotid artery occlusive disease or arteritic/non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.9,26

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

A thorough physical examination along with appropriate in-office testing (visual field, OCT, OCT angiography, fundus photography) should be performed as indicated. On rare occasions, retinal vasospasm can be observed on funduscopic examination.

Assuming a normal ophthalmic examination, further workup is dictated by patient age, vascular risk factors and accompanying symptoms. Patients over 50 with vascular risk factors and new onset or worsening symptoms warrant an expedited workup encompassing immediate serology for inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) and carotid imaging to rule out GCA and carotid occlusive disease, respectively. A baseline electrocardiogram, MRI of the brain and CTA or MRA of the head and neck should follow if serology and carotid imaging are normal. Patients over 50 without vascular risk factors and progressing or new onset symptoms can be worked up within 24 to 72 hours.

Workup can be bypassed in younger patients with long-standing symptoms, no vascular risk factors, a normal ophthalmologic exam and symptoms indicative of migraine. Young patients with symptoms that deviate from that of classic migraine, are new in onset and/or are worsening warrant further workup for hypercoagulopathies along with brain MRI. Once all underlying etiologies have been excluded, only then can a diagnosis of retinal migraine be made. If persistent deficits remain (e.g., visual field defects, RAPD), the patient no longer fulfills ICHD-3 criteria for retinal migraine and other thromboembolic etiologies must be ruled out.9,24,26

Management Approach

Treatment for migraines accompanied by headache starts with attempting to eliminate potential triggers for attacks.27 When this is not enough to keep migraines at bay, medication may be indicated. Medication may be either abortive (taken when the headache starts) or prophylactic. Patients who suffer from recurrent or chronic migraine occurrences warrant prophylactic treatment.27

For mild to moderate migraines, many people are able to relieve the headache pain with an over-the-counter pain reliever such as acetaminophen or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). This is typically the first line of treatment. If over-the-counter pain relievers are not enough to mitigate the migraines, consider a consult with a neurologist or internist for treatment with medications.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Although numerous drug classes exist in the abortive management of migraine, triptans are the most common, especially in patients who do not respond to or tolerate simple analgesics or NSAIDs. Triptans are selective 5-hydroxytriptamine serotonin receptor agonists that, among other things, help prevent vasoactive neuropeptide release and block transmission of pain signals. They are well-tolerated by most migraineurs but should be used with caution among those with an established history of hypertension.28 For these patients, calcitonin gene-related peptide blockers (gepants) and serotonin 5-HT 1F agonists (ditans) have a better safety profile.29

Migraine prophylaxis is indicated for individuals who experience four or more headaches per month or eight or more headache days per month. First-line agents for prevention include divalproex, topiramate and beta blockers. The side effects of these agents are problematic for many individuals. CGRP inhibitors are gaining popularity as prevention agents, given their favorable safety profile and minimal side effects.

Antiemetic medications can be taken during a migraine event if needed for nausea or vomiting. Stroke is an increased risk in patients who have migraines, even more so if the patient is a smoker, so smoking cessation should be strongly encouraged.10

Conclusion

In summary, the visual symptoms of migraine are a frequent cause of patient visits to the optometrist or ophthalmologist. Migraine aura accompanied by headache in a youthful patient is a straightforward diagnosis that does not require further investigation. Migraine aura without headache is a diagnosis of exclusion requiring a comprehensive investigation for thromboembolic disease. Finally, retinal migraine is exceedingly rare and must meet all IHS criteria stated in this paper. If these criteria are not fully satisfied, such patients must be promptly worked-up for thromboembolic disease associated with transient monocular vision loss.

As eyecare providers, we are uniquely equipped to help diagnose visual auras by ruling out any other ocular pathologies from being the cause of a subjective visual disturbance. Once a diagnosis of ocular migraine is made, patient reassurance and referral to a primary care provider can help improve our patient’s quality of life.

Dr. Messner is Vice President for Strategy & Institutional Advancement at the Illinois College of Optometry. He also holds the rank of professor of optometry at ICO. He is the immediate past Chair of the Neuro-ophthalmic Disorders Special Interest Group of the American Academy of Optometry.

Dr. Rockne is a clinical ocular disease/primary care resident at the Illinois College of Optometry. His professional interests include emergency eye care, neuro-ophthalmic disease and medical retina.

Dr. Turner is a staff optometrist and residency and externship coordinator at the Jack C. Montgomery VA Medical Center in Muskogee, OK. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and serves as adjunct faculty for several colleges of optometry.

Dr. Burress is also a staff optometrist at the Jack C. Montgomery VAMC. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and currently serves as an executive member of the Oklahoma Association of Optometric Physicians Congress Committee. Dr. Burress also serves the ACOE as a chairperson for residency accreditation visits. None of the four authors have any financial interests to disclose.

1. Shareef AH, Dafer RM, Jay WM. Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of primary headache disorders. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23(3):169-77. 2. The International Classification of Headache Disorders – ICHD-3. ICHD. 3. Digre K. More than meets the eye: The eye and migraine-What You Need to Know. J Neuroophthalmol. 2018;38(2):237-43. 4. Al Khalili Y, Jain S, King KC. Retinal Migraine Headache (updated Jul 21, 2022). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507725. 5. Pradhan S, Chung SM. Retinal, ophthalmic, or ocular migraine. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(5):391-7. 6. Hill DL, Daroff RB, Ducros A, et al. Most cases labeled as “retinal migraine” are not migraine. J Neuroophthalmol. 2007;27(1):3-8. 7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. 8. Viana M, Sances G, Linde M, et al. Clinical features of migraine aura: Results from a prospective diary-aided study. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(10):979-89. 9. Chong YJ, Mollan SP, Logeswaran A, et al. Current perspective on retinal migraine. Vision (Basel). 2021;5(3):38. 10. Pane A, Miller NR, Burdon MA. The Neuro-Ophthalmology Survival Guide. Elsevier (2017). 11. Gelfand AA, Gelfand JM, Prabakhar P, et al. Ophthalmoplegic “migraine” or recurrent ophthalmoplegic cranial neuropathy: new cases and a systematic review. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(6):759-66. 12. Cutrer FM. Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of migraine in adults. UpToDate. Feb 13, 2023. www.uptodate.com/contents/pathophysiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-migraine-in-adults 13. Maniyar FH, Sprenger T, Monteith T, et al. Brain activations in the premonitory phase of nitroglycerin-triggered migraine attacks. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 1):232-41. 14. Schulte LH, Allers A, May A. Hypothalamus as a mediator of chronic migraine: Evidence from high-resolution fMRI. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2011-16. 15. Lai J, Dilli E. Migraine Aura: Updates in pathophysiology and management. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(6):17. 16. Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, et al. Pathophysiology of migraine: A disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(2):553-622. 17. Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL. Liu, Volpe, and Galetta’s Neuro-ophthalmology: Diagnosis and Management. Elsevier (2019). 18. Harriott AM, Takizawa T, Chung DY, et al. Spreading depression as a preclinical model of migraine. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):45. 19. Fraser CL, Hepschke JL, Jenkins B, et al. Migraine aura: pathophysiology, mimics, and treatment options. Semin Neurol. 2019;39(6):739-48. 20. Pourshoghi A, Danesh A, Tabby DS, et al. Cerebral reactivity in migraine patients measured with functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:96. 21. Burger SK, Saul RF, Selhorst JB, et al. Transient monocular blindness caused by vasospasm. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(12):870-3. 22. Biousse V, Newman NJ, Sternberg P Jr. Retinal vein occlusion and transient monocular visual loss associated with hyperhomocystinemia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(2):257-60. 23. Gronvall H. On changes in the fundus oculi and persisting injuries to the eye in migraine. Acta Ophthalmol. 1938;16:602-11. 24. Pradhan S, Chung SM. Retinal, ophthalmic, or ocular migraine. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(5):391-7. 25. Viana M, Tronvik EA, Do TP, et al. Clinical features of visual migraine aura: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):64. 26. Al Khalili Y, Jain S, King KC. Retinal Migraine Headache. 2022 Jul 21. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. 27. Gervasio KA, Peck TJ, Fathy CA, et al. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (2022). 28. DeMaagd G. The pharmacological management of migraine, part 1: overview and abortive therapy. PT. 2008;33(7):404-16. 29. Schwedt TJ, Garza I. Acute treatment of migraine in adults. UpToDate Jun 6, 2023. www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-treatment-of-migraine-in-adults 30. Miller NR, Subramanian PS, Patel VR, et al. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology: The Essentials. Wolters Kluwer (2021). |