|

The Role of Eyelids in Health and Disease

Understanding how the lids can fail is critical to ensuring optimal patient care.

By Victoria Roan, OD

Release Date: February 15, 2021

Expiration Date: February 15, 2024

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: 2 hours

Jointly provided by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and Review Education Group

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Review the anatomy of the eyelids.

- Recognize the impact eyelids have on the ocular system.

- Discuss the role eyelid complications play in dry eye.

- Describe the pathophysiology of common eyelid conditions.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in primary care of the anterior segment of the eye.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Review Education Group. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, and the American Nurses Credentialing Center, to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is accredited by COPE to provide continuing education to optometrists.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Victoria Roan, OD

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Course ID is 71048-AS. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements:

Author: Dr. Roan has nothing to disclose.

Managers and Editorial Staff: The PIM planners and managers have nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group planners, managers and editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

Ocular surface health and functioning eyelids go hand-in-hand. However, the ways the eyelids can fail to protect the eye are often overlooked. As a result, it can be a challenge to understand why treatments that would otherwise work provide no relief to patients. There are a variety of lid conditions that can affect a patient’s eye health, such as dry eye disease (DED), ptosis, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD)/blepharitis and lid lesions, to name a few. To provide effective care, clinicians must understand the pathophysiology of these diseases and their potential impact.

This article highlights these common conditions, while taking a closer look at how compromises to the eyelids can have a cascading effect on the ocular system.

|

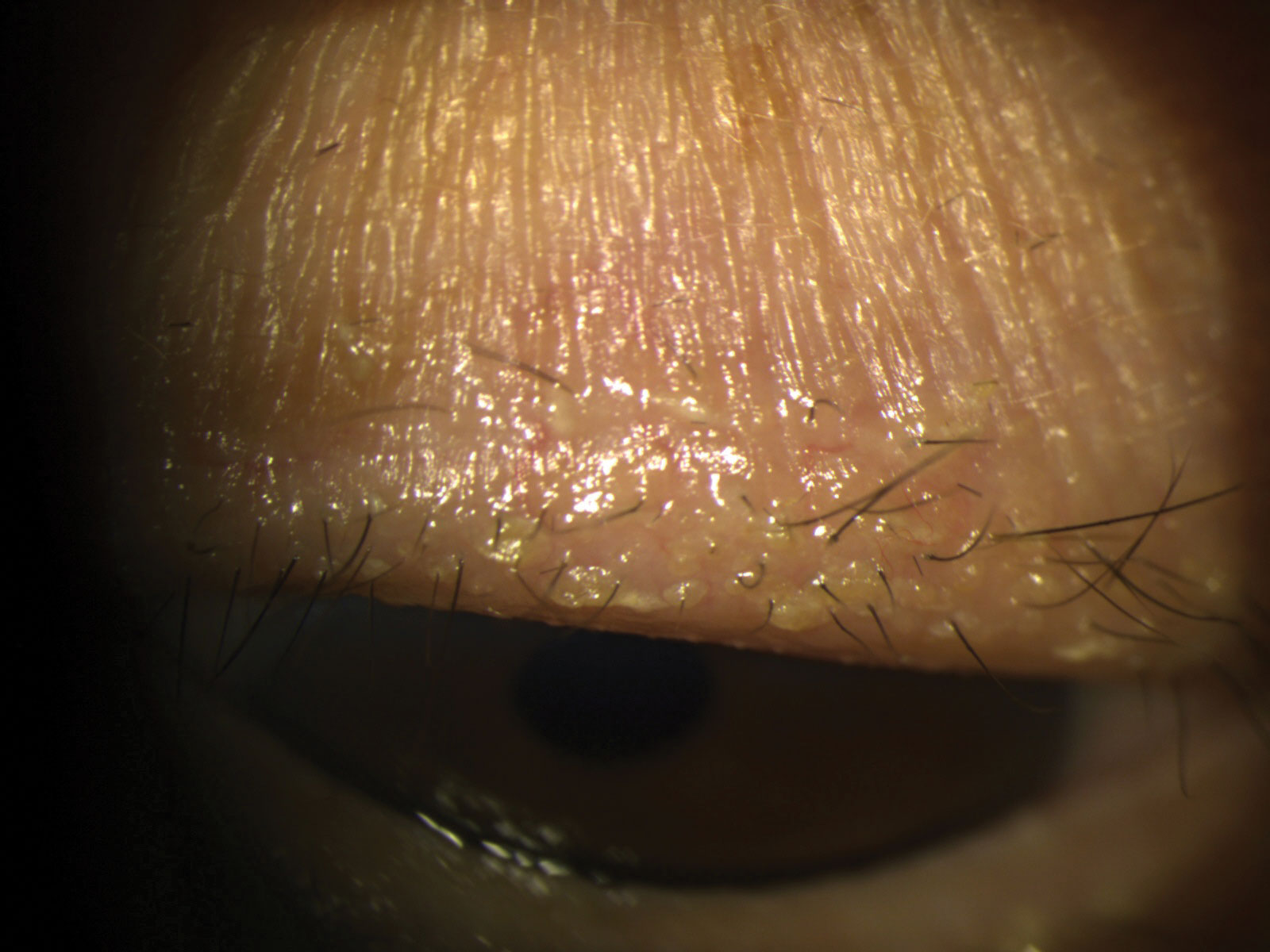

| Stubborn debris and scurf along the base of lashes. The patient was started on a regimen of warm compresses and 0.01% hypochlorous acid lid cleaning routine BID OU. Click image to enlarge. |

The Anatomy of the Eyelid

The eyelid is responsible for the proper lubrication of the ocular surface via 3,000 to 15,000 blinks per day. And yet, it is easy to overlook this adnexal structure that is both protective and supportive of ocular health. Before we can discuss the conditions of the eyelid, it is important to review their anatomy and function to better understand how these structures relate to potential vulnerabilities.

The lid is easily organized into the anterior and posterior lamellae, separated by the orbital septum, which also serves as a protective barrier from infection and inflammation, as in discussions of orbital vs. preseptal cellulitis.

Anterior lamellae. During a comprehensive eye exam, optometrists may briefly scan the structures and function of the anterior lamellae, which is made up of the skin and subcutaneous layers, lid margin and orbicularis oculi muscle. Specifically, we are checking for lash base cleanliness, meibomian gland function, puncta patency and palpebral aperture width.

The most anterior aspect of the lid includes the cilia, flanked by both the sebaceous Zeis glands as well as Moll sweat glands. Adjacent to the nasal canthus, we can observe the superior and inferior puncta, which are positioned inward and staggered so as not to meet each other when the lids are closed. Next are the structures of the eyelid margin, which include the muscle of Riolan, which presents during slit lamp exam as a narrow band of gray between the lash base and meibomian gland orifices and is an extension of the orbicularis oculi muscle.

The orbicularis itself is separated into orbital and palpebral parts, both innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII). The orbital section is comprised of voluntary muscle fibers responsible for forced lid closures. The palpebral section consists of both voluntary and involuntary innervation and is responsible for the blink reflex. The latter houses Horner’s muscle, which constricts the medial aspect of the lids to direct tears to the puncta for drainage.

|

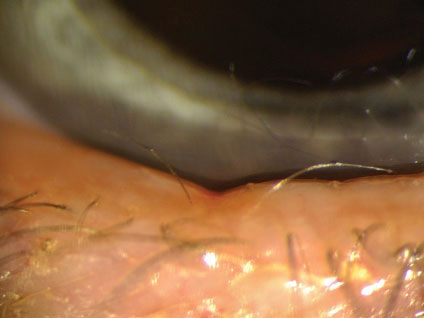

| A 68-year-old female presents with symptoms of foreign body sensation and itchiness. SLE found clogged meibomian glands with mild marginal telangiectasia. Click image to enlarge. |

Posterior lamellae. As we move posteriorly past the orbital septum, the levator palpebral superioris muscle is innervated by CN III. Along with Whitnall’s ligament, the lid moves in a vertical up-and-down motion with each blink, rather than a horizontal movement of anterior to posterior.

The tarsus of the upper and lower lids is made up of dense connective tissue, which houses the meibomian glands responsible for the oil layer of the tear film. The upper tarsus contains more meibomian glands than the lower tarsus. Another contributor to lid opening is the sympathetically innervated Müller’s muscle, which originates from the levator superioris near the Whitnall’s ligament and attaches to the superior aspect of the upper tarsus. This muscle is affected and leads to ptosis in Horner’s syndrome.

Lastly, the most posterior aspect of the lid is the palpebral conjunctiva, which we easily observe with lid eversion. The conjunctiva extends from the palpebral aspect to the fornix and transitions to the bulbar conjunctiva. It is home to the goblet cells, which are dispersed in their highest concentration in the fornices, inferior nasal bulbar conjunctiva and the line of Marx on the lid margin, where the act of blinking spreads the tear film across the ocular surface.

Vasculature. Several branching blood vessels supply the eyelid, stemming from both the external and internal carotid arteries. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the superior and inferior palpebral arteries arising from the ophthalmic artery that originates from the internal carotid. These vessels begin medially and travel horizontally 2mm to 3mm about the lid margins, creating the superior and inferior marginal arterial arches. Along the superior eyelid, the marginal arcade then expands to supply the superior peripheral arterial arcade via vertical vessels to cover the overall surface area of lid structures. This network sits superficially over Müller’s muscle, where it is easily susceptible to trauma and noticeable vascularization. Treatments such as intense pulsed light (IPL) can target both the vasculature and meibomian glands when managing DED.

|

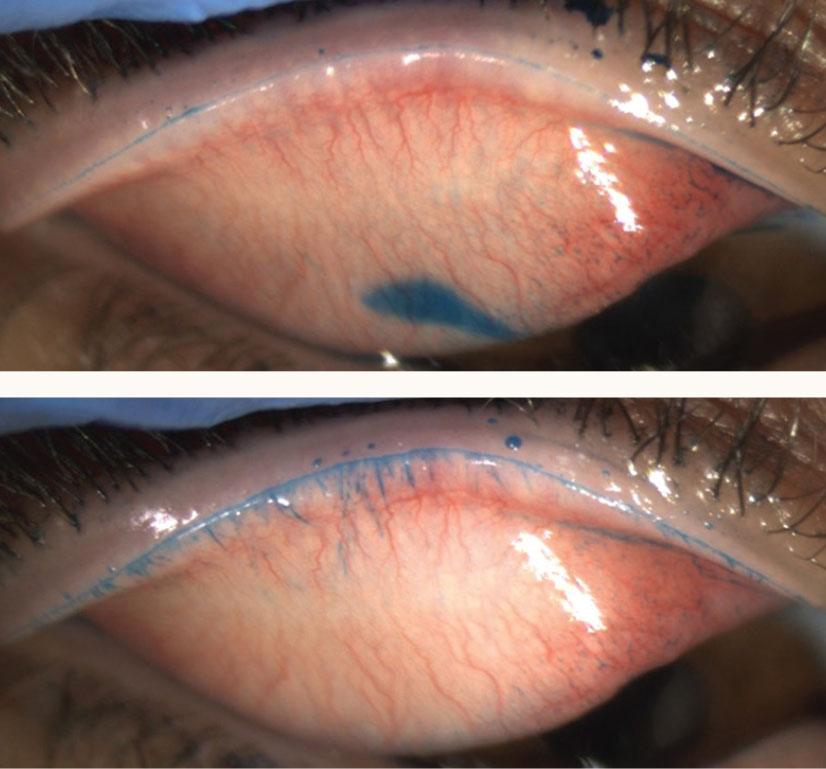

| Chalazia are granulomatous lid lesions arising from blockage of the distal meibomian glands. Photo: Joseph Sowka, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Ocular Surface Disease Factors

Now, let’s talk about the ways lid dysfunction can manifest, as well as the impact it has on the eye and the symptoms that present as a result.

Our examination of the eyelid should include a complete history of the presentation, which is crucial for determining proper diagnosis, effect on ocular surface health and treatment plans. Compromise in one or more aspects of tear film production, distribution and retention provided by the eyelids might result in disruption of the delicate homeostasis of the ocular surface.

Meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis. These conditions do not always occur concurrently, but where there’s one, there’s likely mild presentation of the other. Both, however, present with slowly worsening symptoms over time. Blepharitis and MGD are extremely common contributors to evaporative dry eye. In recent years, increasing innovation and attention to eyelid hygiene have been expended to combat these problems. The goal for the provider is to diagnose and treat the condition early—before the patient becomes symptomatic.

Lash base debris, erythema, telangiectasia and permanent lid margin deformations are often detected with slit lamp examination when the patient presents with complaints of irritation, burning or itching of the eyes unresponsive to occasional artificial tear use. Commonly, patients with permanent eyeliner will present with meibomian gland dropout, and those with lash extensions can have trapped debris and bacterial buildup due to poor lid hygiene, resulting in low-grade lid inflammation and ultimately infection. Proper education on their risk factors for developing chronic issues should be reviewed and a management plan initiated. Even without these cosmetic indicators, a yearly evaluation of lid health for your patients is warranted.

Either a bacterial or mite infestation can result in chronic inflammation of the lid margin, which promotes obstruction of the meibomian glands. Ideally, yearly evaluation of lid hygiene and prompt education on the effects of these findings can help prevent symptoms altogether. Anterior segment photos are beneficial for documentation and may help convince patients to start preventative treatments such as warm compresses and daily lid scrubs. For lashes with stubborn lid debris and scurf, mechanical exfoliators, such as BlephEx, can be used in clinic before the patient begins their at-home maintenance routine. In addition, consideration for omega-3 supplements can also be reviewed due to their anti-inflammatory benefits and ability to balance tear film osmolarity by improving meibum quality and, therefore, tear break-up time (TBUT).

Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium and Corynebacterium are the most common bacterial causes of chronic blepharitis.1 Furthermore, increased prevalence of Demodex, either D. folliculorum or D. brevis, is expected with age. With the longer life expectancies of the population, optometrists should anticipate more patients presenting with associated adnexal complaints. One study demonstrated a clinically significant increase in Demodex infestation in those with chronic blepharitis (80.36%) compared to healthy subjects (45.65%), which is corroborated by similar research.1-3

Therefore, when considering treatment options for chronic blepharitis, both a broad-spectrum antimicrobial and an anti-Demodex therapy should be implemented simultaneously. A low-dose (20mg) oral doxycycline twice a day for a month has been shown to be effective in these cases due to is antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties.4 Alternatively, 1.25g of oral azithromycin for five to seven days is also effective.5 Early and aggressive treatment before the ocular surface is damaged and/or irreversible lid margin alterations occur will lead to better retention of patent meibomian glands and, ultimately, a better prognosis for long-term tear film health.

|

| A 56-year-old female presented with lower lid notching and distichiasis without entropion, which can indicate a chronic inflammatory etiology. The patient was started on omega-3 supplements and daily lid hygiene. She returns for epilation every three to four months, as she is disinterested in surgical intervention. Click image to enlarge. |

Lid lesions. When the lid margin is affected by bacterial biofilms and mites, without proper management the meibomian and Zeis glands will become susceptible to infection. These acute inflammatory processes are typically localized elevations and are the majority of preventable eyelid conditions seen in practice.

Hordeola result from infection, predominantly staphylococcal, which results in painful bumps or styes made up of polymorphonuclear leukocytes along with tissue necrosis. For external hordeolum infections affecting the Zeis glands, a frequent schedule of warm compresses and a topical steroid with a macrolide antibiotic treatment can be highly effective in resolving persistent and painful lesions.6 Internal meibomian gland hordeola are deeper and may require an oral antibiotic for most effective treatment along with warm compresses.

A chalazion is a painless, inflammatory lipogranulomatous lesion due to a blockage of the distal meibomian glands. They are commonly associated with inflammatory systemic conditions like acne rosacea. They can present acutely or as a result of poor compliance with hordeolum treatment. The backed-up lipids build up in the glands and result in an immune response of neutrophils surrounding and encasing the material. Externally, the lid appears focally elevated with less erythema than a hordeolum.

Intralesional injection of a steroid or surgical intervention with transconjunctival incision and drainage may be necessary if conservative treatments are ineffective. Even if the lesion is painless and the patient is unbothered by the appearance, treatment is still recommended, since the lesion may expand and cause distortions to the lid margin as well as changes to vision from induced astigmatism.6 Only 25% to 50% of chalazia fully resolve on their own.7 Poor lid apposition to globe, ectropion or entropion with trichiasis and hyperkeratinization from lid pathology will contribute to worsening ocular surface disease.

If the patient’s signs and symptoms persist following topical and oral therapies, referral to a lid specialist for triamcinolone acetonide injection, or incision and curettage, is appropriate. Optometric comanagement following incision and drainage is important, since post-op scarring and trauma to lid structures may lead to increased dry eye symptoms. Emphasizing proper post-op care to patients—including applying moist heat frequently TID for 10 minutes each time as well as avoiding eye rubbing, getting water in the eyes and using makeup for up to a month—will help with the healing process. Post-op topical antibiotics are typically used for one week, and topical steroids may be tapered throughout the month following the procedure; these instructions are typically reviewed with the patient at their surgical site.

If recurrent nodules appear in the same location in older patients, referral to an oculoplastic surgeon is also indicated to rule out a sebaceous cell carcinoma. As with any lid surgery, mechanical deficiencies may result, and careful assessment of function should be performed during post-op care.

|

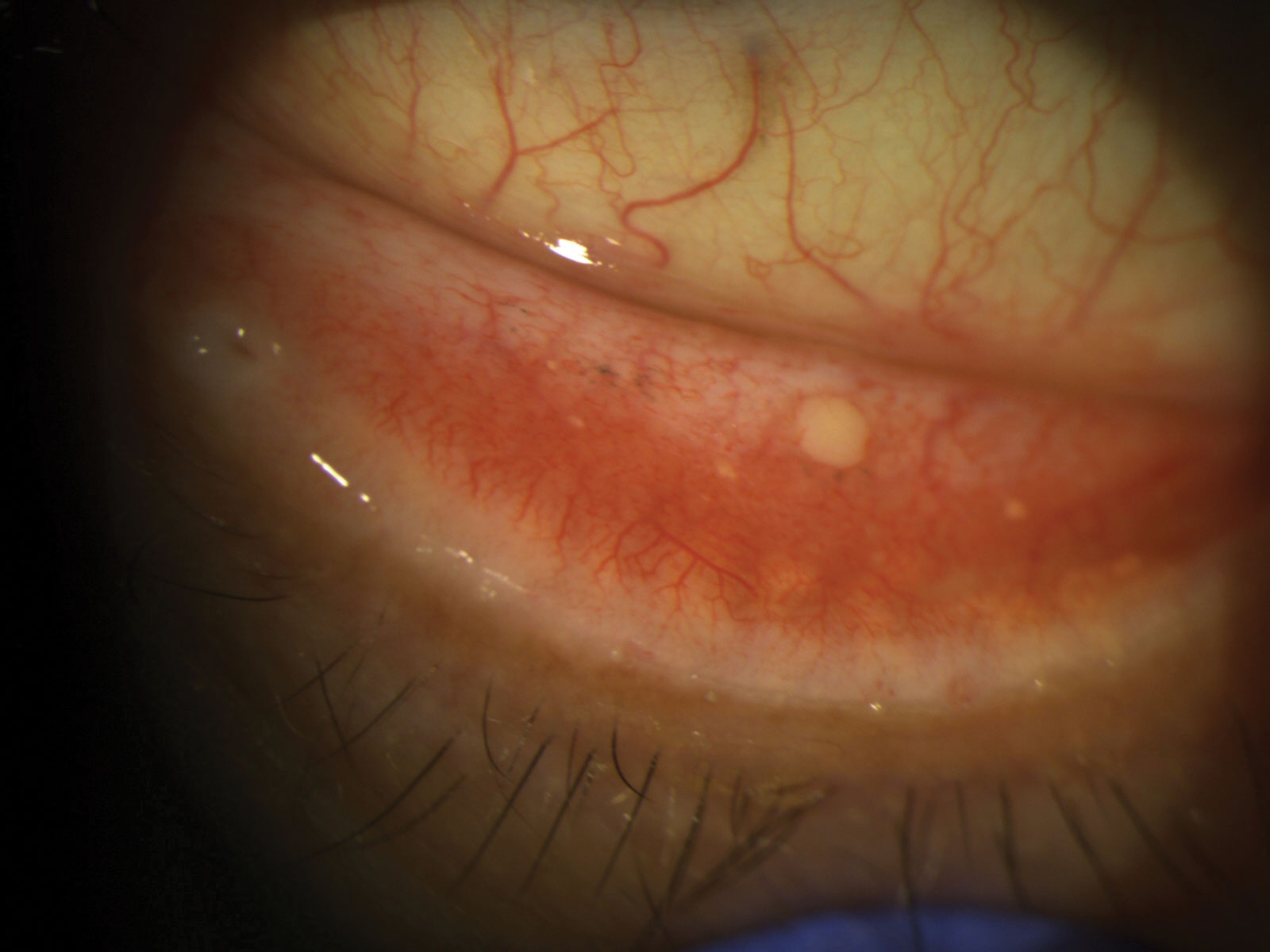

| The top image reveals the line of Marx in a case of lid wiper epitheliopathy, while the bottom image shows additional proximal LWE staining. Photos: Christopher Lievens, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Mechanical lid deficiency. Conditions involving lid mechanics, which can occur in adults and children, can limit or even completely block normal vision. With ptosis, whether congenital or acquired in etiology, the levator muscle is unable to fully retract. Ptosis secondary to nerve paralysis may resolve without surgical or topical intervention. For instance, cases of ischemic third nerve palsies are typically self-limiting, and 80% to 85% of patients notice resolution in three to six months.8 An acute presentation of unilateral ptosis should signal the need for careful patient history and assessment of the pupils to rule out Horner’s syndrome. Again, the causes may vary, so treatment is based on the location and cause of the sympathetic nerve interference. A prompt referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist may ultimately save a patient from a serious systemic condition.

However, most commonly, aponeurotic ptosis is due to a thinning and loss of levator muscle tone and is amenable to surgical intervention. Depending on the surgical approach, the patient risks exacerbation of dry eye if there is over-correction or damage to the lid structures and vasculature.9 Therefore, surgery is typically not recommended unless the patient has demonstrable visual symptoms. However, if surgery is indicated, the patient should be thoroughly educated on the risk of increased dry eye as a post-op complication. Preoperative optimization of the tear film and postoperative management for DED should be initiated.

Weakening of the lower lid retractors and canthal tendon due to age or history of trauma will result in an inward (ectropion) or outward (entropion) turning of the lid margin. It is more commonly seen in the elderly population and primarily affects the lower lid. In ectropion, poor apposition of lid margin to globe results in poor tear film spreading and retention. The patient will present with exposure keratitis. In addition, the meibomian glands are unable to properly release the lipid layer of the tear film.

In entropion, however, the patient is at high risk for superficial corneal abrasions from secondary trichiasis and corneal infections brought on by the increased proximity of natural bacterial flora of the lid. The patient often notes a persistent foreign body sensation along with mucus discharge, depending on the condition’s chronicity. Both entropion and ectropion are thought to be caused by increased levels of elastolytic activity, resulting in a loss of elastic fibers in tissues. The most common elastolytic enzymes belong to the matrix metalloproteinase family, which are overexpressed in a variety of conditions, such as local ischemia, inflammation and chronic mechanical trauma.10

Referral to an oculoplastic surgeon for either condition can restore normal eyelid architecture to enable proper lid closure and improve ocular protection and tear film spreading. Non-surgical management includes frequent lubrication, eyelid masks or ointment, use of bandage contact lenses and management of concurrent eyelid disease, such as MGD or blepharitis, for improved comfort in the interim. Surgical approaches may depend on the presence of orbicularis oculi over-action, horizontal laxity and/or vertical laxity.

Another common yet often overlooked contributor to poor ocular surface health is lagophthalmos. Complete eyelid closure with an involuntary blink is vital to proper tear film distribution and, therefore, a critical element for maintaining a healthy ocular surface. Common etiologies include cosmetic eyelid surgeries for dermatochalasis, ptosis repair, Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA) injections, Grave’s disease, floppy eyelid syndrome (FES), lid deformities from lesions or trauma, use of scleral lenses, ectropion and reduced blink rate from excessive screen time.

Patients may present with increased dry eye symptoms first thing in the morning due to nocturnal lagophthalmos, particularly if using a CPAP machine for sleep apnea. Presence of lagophthalmos can be assessed at the time of the exam by measuring the palpebral fissure opening upon inferior gaze and gentle closure of lids, documenting the opening in millimeters to determine degree of the condition. The Korb-Blackie (KB) lid light test is also helpful in diagnosing the weak or lacking protective seal between upper and lower lids.

Acute cases should have a thorough exam of cranial nerve function with emphasis on orbicularis oculi muscle motility. Examine the amount of effort needed to achieve full lid closure as well as the presence of Bell’s phenomenon, where the eye naturally rolls upward on voluntary lid closure. Those with a poor Bell’s reflex are prone to keratopathy. Prolonged exposure of corneal surface and subsequent exposure keratitis can be noted on slit lamp exam with fluorescein or lissamine green staining occurring on the inferior cornea and conjunctiva. Measure TBUT and corneal sensitivity between the eyes, especially if there is a unilateral presentation.

Unfortunately, in chronic cases, corneal epithelial decompensation, sterile or infectious corneal ulcerations, neurotrophic keratitis or corneal neuropathic pain may occur. As previously mentioned, the facial nerve (CN VII) innervates the orbicularis oculi, which closes the eyelids. CN VII palsies or damage will result in poor lid closure and inhibit the blink reflex and associated lacrimal pumping mechanism. As a result, the patient may have both a secondary aqueous and secondary evaporative dry eye.

Determining cause is important in dictating management and possibly comanagement with the patient’s primary care provider and a neuro-ophthalmologist. For maintenance and symptom relief, these patients may benefit most from a moisture-preserving sleep mask to prevent overnight exposure and exacerbations of signs and symptoms. Unfortunately, chronic cases may ultimately require surgical interventions such as a tarsorrhaphy, gold weight implantation, lower eyelid tightening and elevation, or upper eyelid retractions and levator recession to prevent corneal ulcerations.11

If typical dry eye treatments are ineffective, eyelid laxity may be a contributing factor for poor tear film retention and distribution. FES is often seen in patients with sleep apnea, glaucoma and keratoconus. Floppy eyelid syndrome can exacerbate MGD, superficial exposure keratitis, giant papillary conjunctivitis and superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. During the examination, a highly elastic and easily everted upper lid is an indication of FES. Treatment for such a presentation can include management of increased inflammatory agents on the lid margin as well as referral to the patient’s PCP for sleep apnea evaluation.

The role of the optometrist is to help maintain eye integrity while also comanaging with the patient’s primary care provider to address systemic conditions that may contribute to this lid finding. Referral to oculoplastic surgeons is often indicated.

|

| Chronic ocular allergies can sometimes result in conjunctival concretions. This patient had complaints of persistent foreign body sensation, which resolved once the concretion was excised. Click image to enlarge. |

Conjunctival factors. Most recently, lid wiper epitheliopathy (LWE) has been uncovered in patients with dry eye symptoms who present with normal TBUT times and normal Schirmer’s test values. Oftentimes, these patients also have a negative fluorescein corneal staining. The “lid wiper region” sits just posterior to the line of Marx, where the lid’s marginal conjunctiva opposes the ocular surface from the medial puncta to the lateral canthus horizontally.12

LWE occurs posterior to the line of Marx, extending on to the conjunctiva. Lissamine green can be used to identify the Marx line, which—when normal—is a thin band identifying the mucocutaneous junction. LWE presents as a horizontal expansion posterior to the line of Marx. The primary cause of LWE is hypothesized to be due to the friction when lubrication between the lid wiper and the ocular surface or a contact lens is insufficient. It is associated with abnormal blink patterns, irregular lid margins, tight lids as in Grave’s disease, high myopia and aggressive eyelid surgery.

Several studies have shown an increased presentation of LWE in long-term contact lens wearers.13,14 One study recognized that 76% of non–contact lens wearing patients with dry eye symptoms, yet no corneal findings, presented with LWE.9 Essentially, diagnosis of LWE before ocular surface presentations may be valuable in signaling earlier diagnosis and preventative treatment of DED.

The conjunctival goblet cells are responsible for the production of a portion of the tear film’s mucin layer. Though mucin consists of the thinnest layer of the tear film, these glycoproteins are important in making the tear film hydrophilic, not only allowing the tear film to stay on the ocular surface, but also aiding in the smooth and even dispersion of the aqueous layer across the eye. The main ocular mucins contributing to the tear film are MUC1, MUC5AC and MUC7.

MUC1 helps keep foreign bodies and inflammatory agents from adhering to the eye, while MUC7 is thought to have antibacterial properties. Both are important for limiting retention of pro-inflammatory molecules, which can exacerbate dry eye symptoms. MUC5AC represents the gel-forming mucins that are most abundant on the ocular surface and play the largest role in promoting tear film equilibrium.

Loss of goblet cells will result in decreased mucin production, thereby rendering them unable to fully function properly to maintain lubrication on the ocular surface. Common contributors to loss of goblet cell density include over-use of eye drops with preservatives, vitamin A deficiency, chemical injuries and chronic conjunctival inflammation. Ultimately, this may be the most difficult component of the tear film to supplement and treat. Current studies have shown some benefits of topical vitamin A to increase mucin production or cyclosporine A to increase production of goblet cells in addition to aqueous production.15,16

Other culprits capable of resulting in the chronic symptoms of eyelid-induced dry eye include a history of rosacea or eyelid eczema, chronic allergies and even some acute viral infections.17 Historically, intense pulsed light has been used by aestheticians and dermatologists to manage the inflammatory responses associated with both rosacea and eczema. The treatment helps reduce the signs of redness and superficial blood vessels. As mentioned earlier, IPL can also improve similar symptoms associated with chronic lid diseases like MGD, by targeting the telangiectatic vessels as well as the thickened meibum that causes clogged glands.

Separately, chronic allergies may be a result of cosmetics or cosmeceuticals. An often-overlooked culprit for recurrent blepharitis and MGD is a red dye called Carmine that is commonly used in eyeliners and eye shadows. Raising awareness to the potential for patient sensitivity to this ingredient will help prevent permanent distortions from chronic inflammation. Though not directly affecting specific components responsible for creating a balanced tear film, palpebral conjunctival irregularities such as follicles, large capillaries and pseudomembranes will all contribute to mechanical friction across the ocular surface.

Take-home Message

Given the link between ocular surface health and the eyelids, focusing treatment on the ocular surface without also addressing lid contributors is an ineffective way of resolving patient symptoms. Artificial tears alone will only offer temporary relief and prevent further progression of any eyelid disease. Researchers found that up to 85% of dry eye disease has a lid component, resulting in the need to treat lipid deficiencies, specifically MGD.18

Optometrists have an arsenal of diagnostic tools and management methods to control the narrative on preventative care of the eyelids. We already know how to examine the eyelids. Expensive equipment and techniques are not necessary to begin to apply these basic skills to the prevention of eyelid disease and the treatment of dry eye.

Early efforts at patient education, beginning in the teen years, is a critical step for improving compliance and preventing the sequelae of chronic disease. Optometry is in the position to offer patients affordable and effective management of eyelid health. Efforts to address dry eye and other conditions will be mostly unsuccessful if any underlying causes involving eyelid compromise are not effectively managed.

Dr. Roan is a residency-trained optometrist at Pacific Cataract & Laser Institute in Bellevue, WA. She graduated from the University of Missouri–St.Louis College of Optometry and completed her residency at the Jonathan M. Wainwright Veterans Affairs Medical Center. She has no financial interests to disclose.

| 1. Zhu M, Cheng C, Yi H, et al. Quantitative analysis of the bacteria in blepharitis with demodex infestation. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1719. 2. Bhandari V, Reddy JK. Blepharitis: always remember demodex. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:317-20. 3. Zhao YE, Wu LP, Xu JR. Association of blepharitis with demodex: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(2):95-102. 4. Yoo S, Lee D, Chang M. The effect of low-dose doxycycline therapy in chronic meibomian gland dysfunction. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2005;19(4):258-63. 5. De Benedetti G, Vaiano A. Oral azithromycin and oral doxycycline for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction: a 9-month comparative case series. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(4):464-71. 6. Baharestani S, Nguyen Burkat C, Marcet MM, et al. Stye. EyeWiki. 2015. Available at: eyewiki.aao.org/stye. 7. Goawalla A, Lee V. A prospective randomized treatment study comparing three treatment options for chalazia: triamcinolone acetonide injections, incision and curettage and treatment with hot compresses. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;35(8):706-12. 8. Bagheri N, BN W. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017. 9. Zloto O, Matani A, Prat D, et al. The effect of a ptosis procedure to an upper blepharoplasty on dry eye syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020 Apr;212:1-6. 10. Damasceno RW, Avgitidou G, Belfort R, et al. Eyelid aging: pathophysiology and clinical management. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2015;78(5):328-31. 11. Lawrence SD, Morris CL. Lagophthalmos evaluation and treatment. EyeNet. April 2008. www.aao.org/eyenet/article/lagophthalmos-evaluation-treatment. 12. Korb DR, Blackie CA. Marxʼs line of the upper lid is visible in upgaze without lid eversion. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(3):149-51. 13. Li W, Yeh TN, Leung T, et al. The relationship of lid wiper epitheliopathy to ocular surface signs and symptoms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(5):1878-87. 14. Korb DR, Herman JP, Blackie CA, et al. Prevalence of lid wiper epitheliopathy in subjects with dry eye signs and symptoms. Cornea. 2010;29(4):377-83. 15. Zhang X, Jeyalatha V, Qu Y, et al. Dry eye management: targeting the ocular surface microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1398.de 16. Oliveira RC, Wilson SE. Practical guidance for the use of cyclosporine ophthalmic solutions in the management of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:1115-22. 17. Liu J, Sheha H, Tseng S. Pathogenic role of Demodex mites in blepharitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(5):505-10. 18. Lemp MA, Crews LA, Bron AJ, et al. Distribution of aqueous- deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea. 2012;31(5):472-8. |