|

Keeping an Eye Out for Lacrimal Gland Abnormalities

Understanding how these issues present and their potential implications

is critical for prompt treatment and positive patient outcomes.

By Ashley Kay Maglione, OD, and Kelly Malloy, OD

Jointly provided by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and the Review Education Group

Release Date: May 15, 2023

Expiration Date: May 15, 2026

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: two hours

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in lacrimal gland abnormality management.

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, participants should be better able to:

Recognize the anatomy of a healthy lacrimal gland.

Identify lacrimal gland abnormalities and their potential impact.

Distinguish between various differential diagnoses.

Manage patients with lacrimal gland abnormalities.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: PIM requires faculty, planners and others in control of educational content to disclose all their financial relationships with ineligible companies. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted and mitigated according to PIM policy. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality, accredited CE activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in health care and not a specific proprietary business interest of an ineligible company.

Those involved reported the following relevant financial relationships with ineligible entities related to the educational content of this CE activity: Faculty - Dr. Maglione has no financial disclosures. Dr. Malloy is a speaker and on the advisory board for Osmotica Pharmaceuticals and RVL Pharmaceuticals. Planners and Editorial Staff - PIM has nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group has nothing to disclose.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by PIM and the Review Education Group. PIM is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education and the American Nurses Credentialing Center to provide CE for the healthcare team. PIM is accredited by COPE to provide CE to optometrists.

Credit Statement: This course is COPE-approved for two hours of CE credit. Activity #126026 and course ID 84405-TD. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use: This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. The planners of this activity do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the planners. Refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications and warnings.

Disclaimer: Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient’s condition(s) and possible contraindications and/or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

|

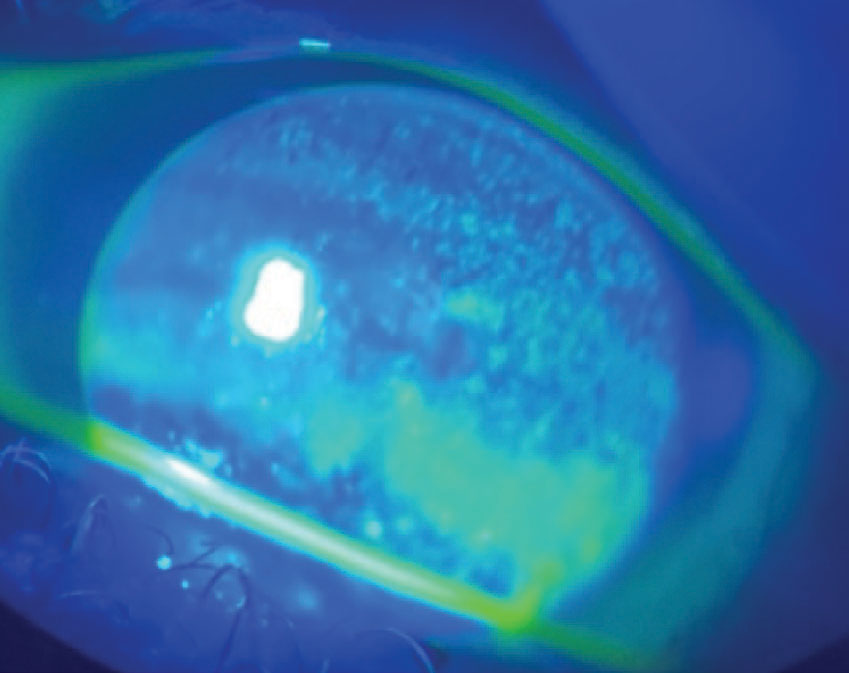

Fig. 1. Diffuse sodium fluorescein staining indicative of corneal dryness OS of a patient with a history of chronic inflammatory dacryoadenitis secondary to GPA. Click image to enlarge. |

The anatomical structure and function of the lacrimal gland makes it susceptible to certain systemic diseases. Lacrimal gland structural change and/or gland dysfunction may be the presenting sign of an underlying systemic disease. Eyecare providers may be the first to see signs of an undiagnosed systemic disease manifesting as a lacrimal gland abnormality; therefore, it is critical that they have a clear understanding of the issues that can impact this structure.1-3

Review of Anatomy

To help doctors identify patients with lacrimal gland abnormalities, first the normal anatomy and function will be reviewed. The lacrimal glands are paired structures located superior temporally in each orbit. The lacrimal glands lie just under the frontal bones—which form the orbital roof—within a depression known as the lacrimal fossa. Anatomically, each lacrimal gland is divided by the tendon of the levator palpebrae superioris, making them appear as a bi-lobed structure with a larger orbital portion and smaller palpebral portion.4

On occasions when our patients with lacrimal gland disease complain of pain, it is the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) that is responsible for the afferent, or sensory, perception. Conversely, efferent innervation to the lacrimal gland arises from the autonomic nervous system.

Specifically, preganglionic parasympathetic fibers travel with the greater superficial petrosal nerve, a branch of the facial nerve (CN VII), and then synapse in the pterygopalatine ganglion in the sphenopalatine fossa. Concurrently, postganglionic sympathetic neurons from the superior cervical ganglion also course through the pterygopalatine ganglion and before reaching the lacrimal gland, travel with the aforementioned parasympathetic neurons via the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve.4

The autonomic innervation allows for the lacrimal gland to achieve its primary function: basal production of the aqueous components of the tear film. Therefore, pathology affecting the lacrimal gland, or its innervation, may give rise to aqueous-deficient dry eye disease. The etiologies of aqueous deficiency are often described in terms of two broad categories: Sjögren’s syndrome (SS)-related dry eye vs. non-Sjögren’s conditions.5 In SS patients, lymphocytes primarily infiltrate the salivary and lacrimal glands, thus producing classic symptoms of dry mouth (xerostomia) and dry eye (keratoconjunctivitis sicca).

If a patient has symptoms suspicious for SS, consider ordering serology for the diagnostic serum antibody markers Ro/SS-A and La/SS-B.6 Examples of non-Sjögren’s conditions that can result in abnormal lacrimal gland aqueous production range from hormonal changes to decreased corneal sensation to autoimmune diseases to secondary effects from pharmacologic drugs.7

|

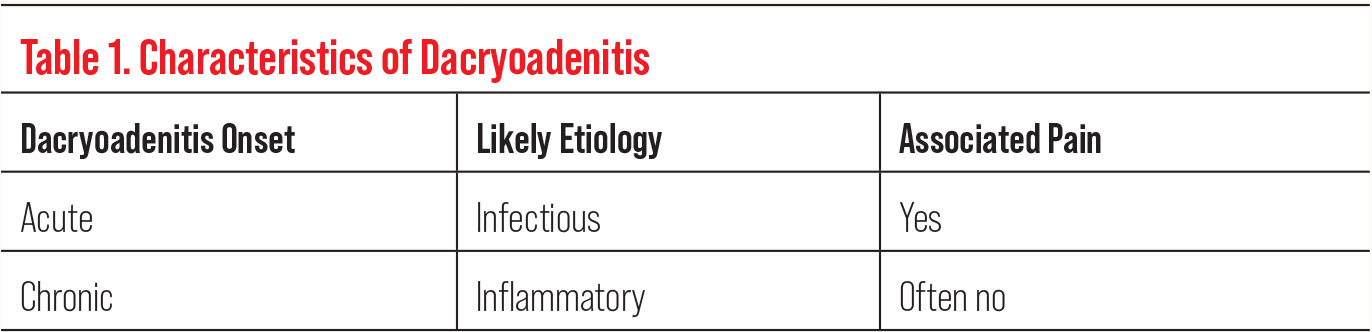

| Click table to enlarge. |

It is important to recognize that the lacrimal gland has a secondary, but arguably equally important, function. The lacrimal gland further contributes to the tears with an ocular immune response by secreting IgA and IgG antibodies via mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). The presence of MALT within the lacrimal gland makes it susceptible to additional systemic conditions, including those that involve immune-mediated responses within lymphoid tissues.4 When the lacrimal gland is affected by these various systemic conditions, associated structural changes may be recognized by the patient and the provider. However, anatomical changes may also be subtle. Therefore, an observant eyecare provider should always “keep an eye out” for lacrimal gland abnormalities.

The use of a case-based approach with the following examples allows us to review lacrimal findings, associated ocular complaints and presentations and differential diagnoses that an eyecare provider may need to consider when encountering an abnormal shape or size variation of a patient’s lacrimal gland(s). Further, we discuss examination tools and management options that a clinician can use to help make cases of lacrimal gland disease less daunting, while also improving patient outcomes.

Case Study 1

A 32-year-old woman presented with complaints of ocular dryness and blurry vision. She reported a history of left eyelid swelling that had prompted her to seek eye care, initially with a different provider. The patient had been diagnosed with a chalazion, and treatment was initiated with warm compresses and ophthalmic ointment containing tobramycin and dexamethasone.

|

Fig. 2. Young woman with bilateral swelling in the lacrimal glands. Click image to enlarge. |

She did not note any improvement, thus surgical excision of the chalazion was then performed. Postoperatively, her swelling continued to worsen, prompting her to seek emergent care. The emergency department proceeded with a frontal orbitotomy and lacrimal gland biopsy to look for involvement of deeper ocular structures; however, results were considered to be consistent with a history of left chalazion.

Shortly after her lacrimal gland biopsy, the patient, who is now pregnant, developed neurologic symptoms of right-sided weakness and slurring of speech. She was again hospitalized and underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with contrast, which revealed pachymeningitis, or inflammation of the outermost layer of the meninges, the dura. She was immediately started on dexamethasone and empiric antibiotics, which improved her neurologic and ocular symptoms rapidly.

She was monitored until neurologic symptoms returned about one month later, and she returned to emergency medicine for a third time. While hospitalized, MRI revealed exacerbated pachymeningitis, but the patient denied further treatment of this condition and left against medical advice.

Ten days later, and now postpartum, she developed progressive neurologic and recurrent ocular symptoms, including swelling in the superior temporal aspect of her left orbit. Because the swelling was in the anatomical location of the lacrimal gland, differentials for lacrimal gland enlargement were considered. As the cause of her lacrimal gland abnormality was likely associated with her systemic symptoms, it was hoped it could potentially facilitate both an ocular and systemic diagnosis.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Discussion. As our patient had been diagnosed with intracranial inflammation (pachymeningitis), it was deemed reasonable to consider that her lacrimal gland swelling may also be due to related inflammation. Enlargement and swelling of the lacrimal gland due to an inflammatory process is known as dacryoadenitis. This condition can occur in all age groups but is most common in children and young adults. Patients with dacryoadenitis usually present with a characteristic S-shaped swollen eyelid with a secondary ptosis related to the lacrimal gland swelling.8 Hyperemia, often localized to the superior lateral conjunctiva, may be present. There may be associated ductional limitations, such as reduced supraduction and adduction, due to mass effect (i.e., physical limitation of movement due to the lesion occupying space).1

Dacryoadenitis may be classified in a variety of ways, including by the nature/timing of the presentation—acute or chronic—and/or may be further classified by etiologies including infectious or inflammatory pathology (Table 1). When dacryoadenitis is chronic, the underlying etiology is often inflammatory, and the patient may not have associated acute pain symptoms. In contrast, acute dacryoadenitis is often infectious in nature and usually painful.8 Due to the context of our patient’s presentation being painless and chronic over a nine-month pregnancy, there was suspicion of an underlying inflammatory etiology.

There are numerous inflammatory systemic conditions that have been associated with dacryoadenitis (Table 2).9 Dacryoadenitis can be a presenting sign in undiagnosed systemic diseases. In fact, the lacrimal gland may be predisposed to inflammation in patients due to the presence of MALT. For instance, a systemic disease associated with lacrimal gland inflammation is sarcoidosis—where orbital findings of dacryoadenitis are seen in up to half of patients who were previously undiagnosed.1,10

In patients with dacryoadenitis, a systemic workup into underlying potential etiologies should be completed, especially in cases that are chronic and/or have signs and symptoms beyond the orbit, such as in the presented case.

Providers may evaluate for undiagnosed systemic disease in part by looking for serum markers, such as those listed in Table 2. For example, elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) or lysozyme may point to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. However, these blood tests may not be specific to one condition and may have false negative or positive results.

Therefore, if suspicion is still high for a specific etiology based on clinical symptoms, despite a negative serum panel, additional testing should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For instance, if a patient with chronic dacryoadenitis also has complaints consistent with sarcoidosis, such as cough or shortness of breath, a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest would be indicated even if ACE levels are normal.11

Additionally, when considering differential causes of dacryoadenitis, a diagnosis may be narrowed, or even definitively made, through biopsy of affected tissue and histopathologic analysis.1,9 In the presented case, an additional biopsy was pursued. Since previous orbital biopsies were unrevealing, a dural biopsy was performed and provided the likely diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

|

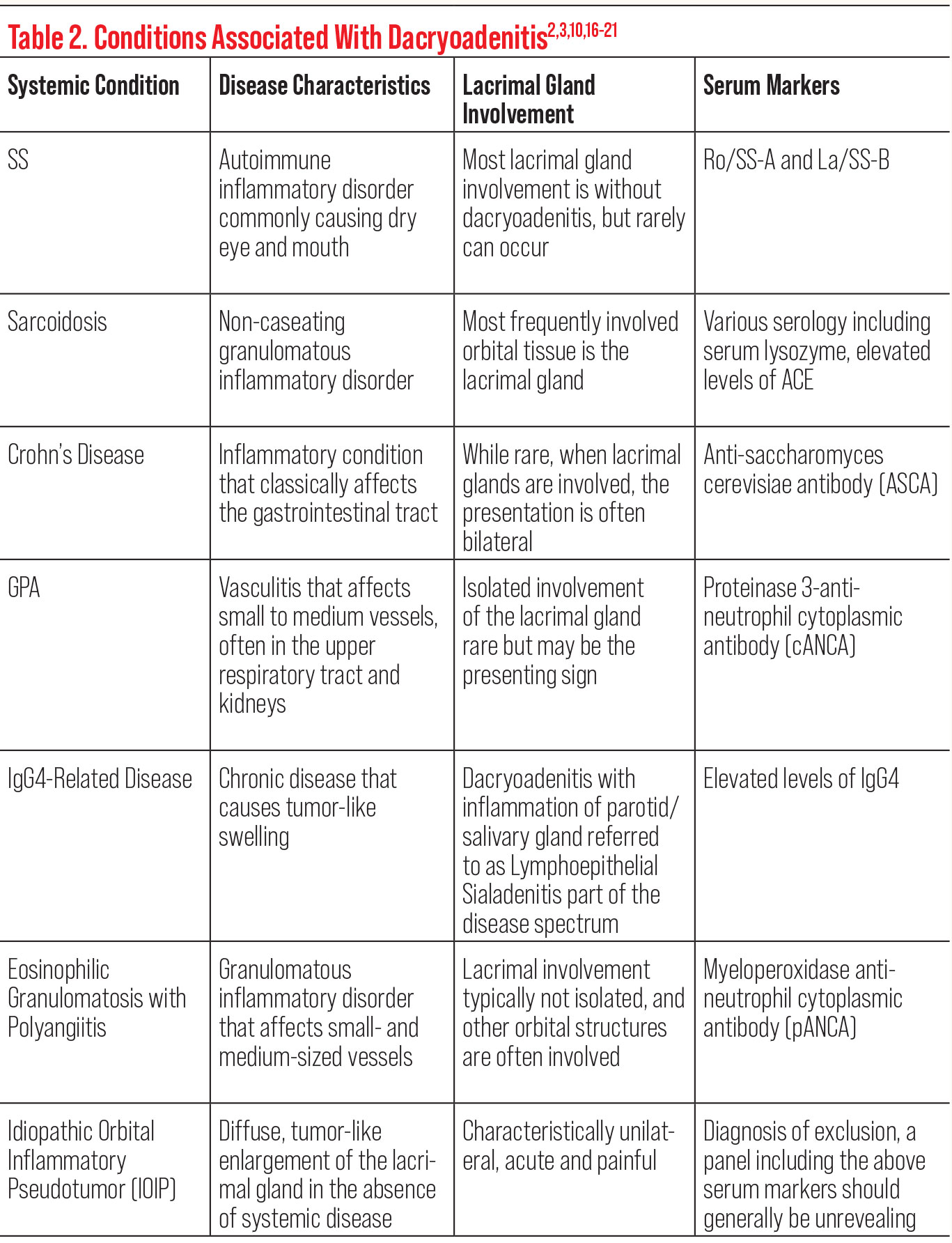

| Click table to enlarge. |

Confounding factors. GPA is an autoimmune vasculitis that classically involves the upper respiratory tract, lungs and kidneys. Orbital involvement occurs in about half of patients with GPA; while isolated involvement of the lacrimal gland is rare in GPA, it may be the presenting sign of the disease as was demonstrated in our patient’s presentation.2,12 In patients with GPA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies react with neutrophil enzyme proteinase 3. Activated neutrophils transmigrate the walls of blood vessels and are then joined by monocytes, resulting in granulomatous inflammation and damage.13

With consideration to the lacrimal gland/eyelid biopsy of our patient’s orbital swelling, it was initially thought to be consistent with her history of chalazion; findings of granulomatous inflammation are characteristics of each pathology.14,15 Despite potential overlap in histopathologic analysis of tissue, when the findings are integrated with the patient’s history, symptoms and performed serologic analysis, diagnostic confidence can be increased.

Treatment. Treatment of dacryoadenitis, unilateral in this case, is usually aimed at managing the underlying etiology. For inflammatory causes, management often involves systemic steroids.1,9 The patient with newly diagnosed GPA was initially treated with pulse IV steroids and then started on rituximab, a monoclonal antibody. There are now numerous monoclonal antibody medications available which are used to treat various autoimmune diseases. Management should be guided and risks assessed.

It is important to evaluate patients with lacrimal gland inflammation for possible underlying systemic diseases, not only from a purely diagnostic standpoint but also to help guide appropriate long-term treatment. For our patient, subsequent neuroimaging demonstrated improved pachymeningitis and resolution of dacryoadenitis; however, this patient presented to the clinic following her diagnosis and treatment with complaints of residual dry eye and blurred vision.

|

Fig. 3. Conjunctival hyperemia in a man with double vision and proptosis. Click image to enlarge. |

Follow-up. On examination, testing demonstrated best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS. The patient exhibited a left ptosis, with interpalpebral fissures measuring 9mm OD and 5mm OS, likely due to her history of surgical incisions in the superior left orbit following biopsy. Additionally, she had restricted ocular motility in the left eye, which may be from residual mass effect. On slit lamp examination, the left cornea demonstrated diffuse corneal staining consistent with her blur complaint and reduced acuity OS (Figure 1). Visual field, OCT and dilated posterior segment examination showed no optic neuropathy or persistent intraocular inflammation.

While the patient’s clinical swelling associated with dacryoadenitis was resolved, it is suspected that the chronic nature of the previous inflammation to the gland may have resulted in reduced primary function of the lacrimal gland, causing secondary aqueous-deficient dry eye disease OS. She was started on judicious preservative-free artificial tears and commercially available topical cyclosporine because of its anti-inflammatory properties. A scleral lens fit was also recommended to potentially assist in her dry eye management and further improve visual clarity.

This case demonstrated that dacryoadenitis can be a presenting sign in an undiagnosed systemic disease. Awareness of a variety of inflammatory systemic conditions that can be associated with dacryoadenitis may expedite diagnosis, guide appropriate treatment and improve both ocular and systemic outcomes.

|

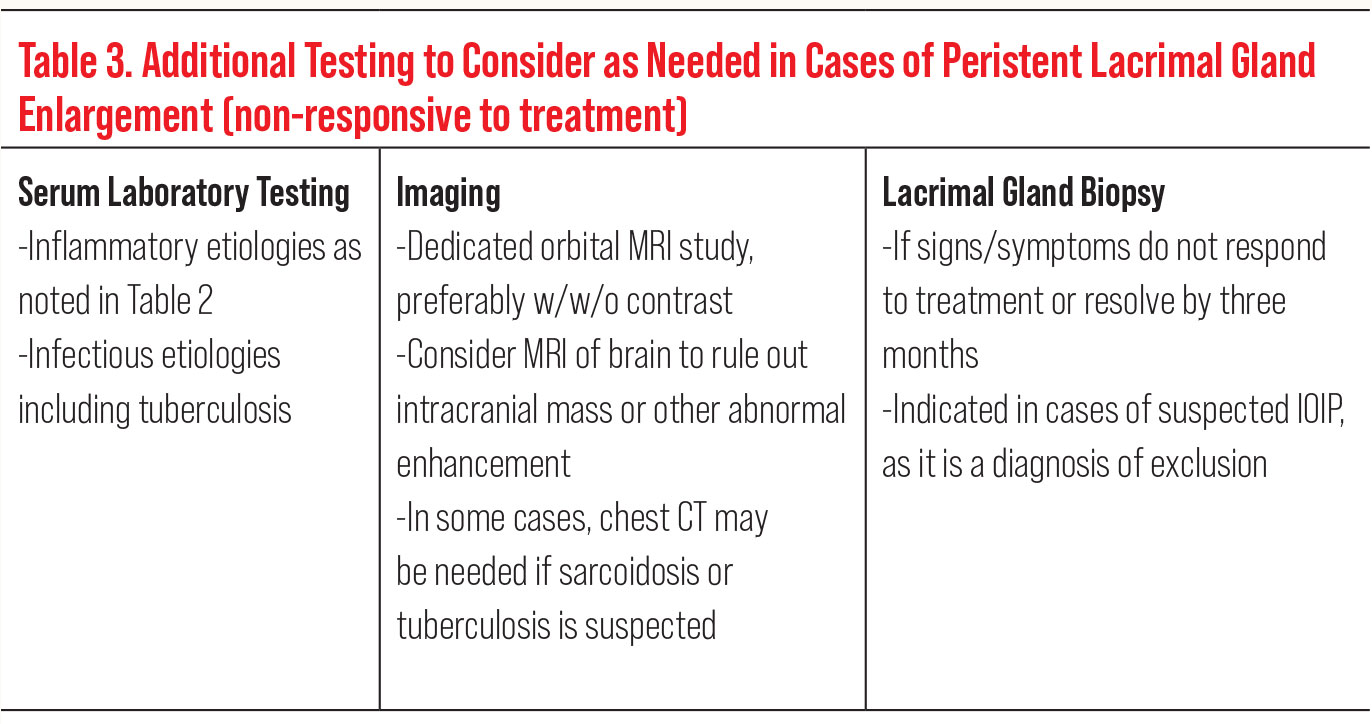

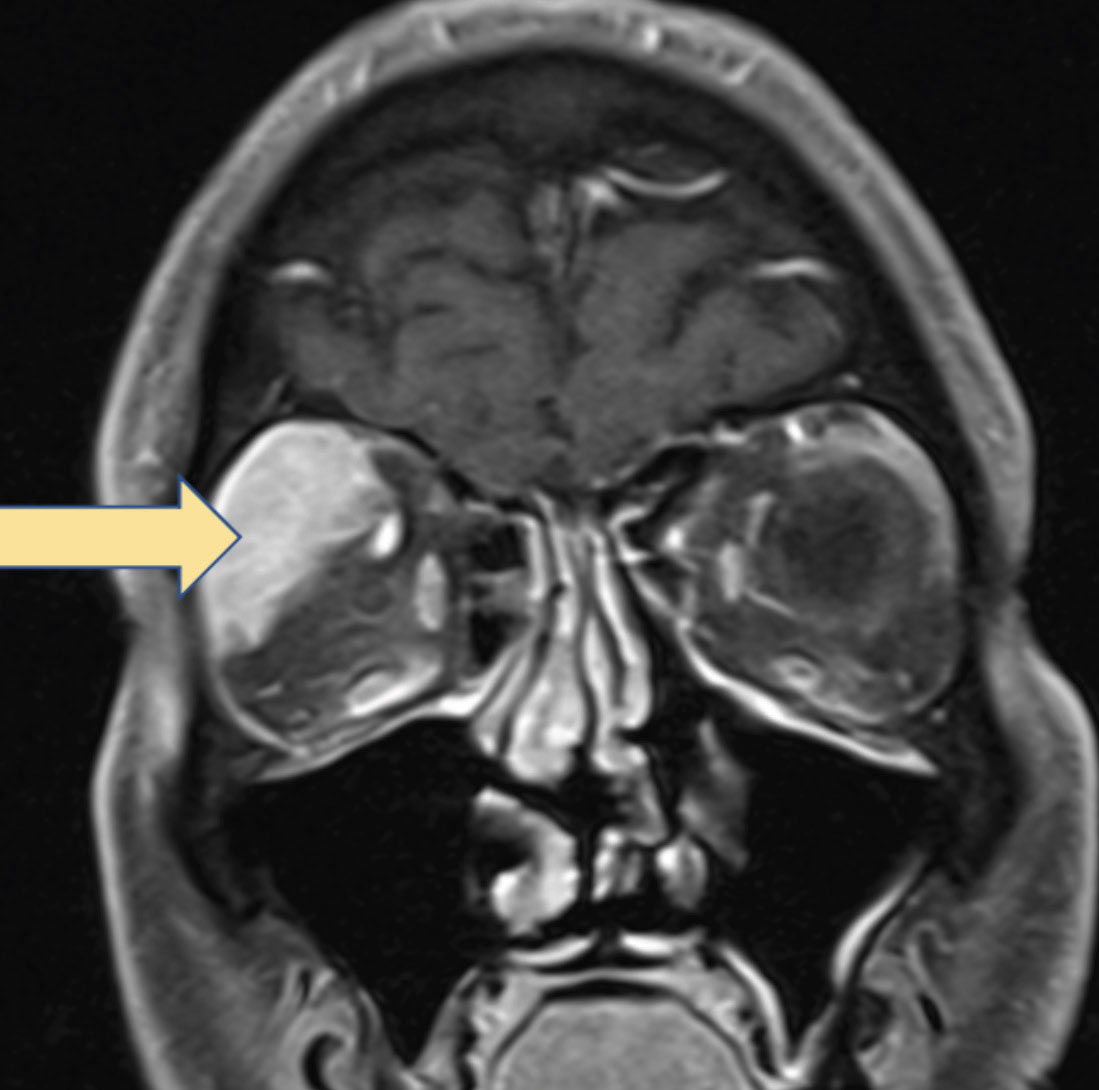

Fig. 4. MRI with contrast demonstrating biopsy-proven B-cell NHL involving the lacrimal gland. Click image to enlarge. |

Case Study 2

A 21-year-old woman presented with a chief complaint of bilateral swelling in the superior-temporal orbit, consistent with the lacrimal gland region (Figure 2). Medical history was remarkable for a relatively recent diagnosis of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) shortly prior to the onset of her ocular symptoms. Examination was largely unremarkable aside from the swelling in the superior eyelid region and mildly reduced abduction ability bilaterally, likely related to physical restriction due to mass effect from the enlarged lacrimal glands.

As with the first case presented, the complaint of swelling in the region of the lacrimal gland again raised the differential of dacryoadenitis. In contrast to the prior case, this patient had a more acute onset of swelling and denied any concurrent systemic inflammatory symptoms or diagnoses. A recent viral (EBV) diagnosis raised the suspicion that her dacryoadenitis was infectious in etiology. In fact, infectious dacryoadenitis is most often viral in nature.

Previously, measles and mumps were commonly reported causative viruses of dacryoadenitis, but now, the most common viral etiology of dacryoadenitis is indeed EBV. Adenovirus, influenza, herpes simplex, herpes zoster and SARS‑CoV‑2 have also been implicated pathogens resulting in dacryoadenitis.21-23

Bacterial dacryoadenitis more often occurs in patients with a history of trauma or conjunctival infection. The most likely pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus, but others include Streptococcus pneumoniae and gram-negative rods.8,9 Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis can result in an atypically chronic infectious dacryoadenitis.8,24

Treatment. Following diagnosis of infectious dacryoadenitis, bilateral in this case, treatment is tailored to the causative pathogen. As such, antibiotics are considered in bacterial cases. If the suspected etiology for dacryoadenitis is believed to be of viral etiology, the condition is usually self-limiting.

Regarding the presented patient, further testing or treatment was not warranted given her recent history of confirmed EBV—as long as the dacryoadenitis resolves in an expected time with expected improvement. However, if infectious dacryoadenitis does not respond to appropriate treatment or is persistent, further workup such as blood work, imaging and possible biopsy may be indicated to rule out more sinister causes of lacrimal gland enlargement (Table 3).

Case Study 3

A 69-year-old man presented with a complaint of right eye redness for 10 days without associated pain, as well as a three-day history of horizontal diplopia in right gaze. All aspects of his afferent visual system evaluation remained normal. However, he exhibited a right-sided ptosis with palpebral apertures of 5mm OD and 8mm OS.

In addition, he had reduced levator function of the right eye at 15mm, with the left eye having 20mm of levator function. He exhibited reduced abduction and supraduction OD. There was an associated esodeviation, greater in right gaze, for which he was symptomatic, and a left hyperdeviation in upgaze, for which he was asymptomatic, partly because of his right-sided ptosis. The culmination of the clinical ocular findings could raise suspicion of a condition such as myasthenia gravis. However, the associated ocular redness was not consistent with such a diagnosis.

The conjunctival hyperemia was moderate and located temporally with greatest conjunctival injection toward the posterior globe (Figure 3). Additional in-office testing helped establish a differential diagnosis for the patient’s complaints and clinical presentation. Exophthalmometry was a valuable key measure in the case, with results of the measurements demonstrating a 4mm proptosis of the right eye (25mm OD, 21mm OS).

External examination of the patient showed a fullness of the right upper eyelid, concentrated temporally and not with the typical jelly-roll pattern often seen with thyroid eye disease. There appeared to be associated right lacrimal gland enlargement. Intraocular pressure, blood pressure and dilated fundus examination were all unremarkable.

Unlike the previous two cases, this patient had no history of concurrent systemic inflammation or preceding infection. However, a thorough history did uncover a remote history of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) affecting his right leg/groin region eight years prior. He underwent surgery for the lymphoma at that time and had no known recurrence, despite oncologic surveillance.

Uncovering a history of lymphoma in a patient presenting with proptosis is very important because lymphoma, like all other cancers, can possibly recur either at the same site or a more remote location. Although not always the case, lymphoma is more common in people with immune system diseases or in those taking immunosuppressant drugs.25 Some infections have been associated with an increased risk of lymphoma, including EBV and Helicobacter pylori infection.26,27

The first sign of lymphoma is often the appearance of enlarged lymph nodes, more likely to arise in the upper portion of the body. Cervical lymphadenopathy is the most frequent head and neck presentation of NHL.25 The lymph nodes become enlarged due to a buildup of abnormal lymphocytes that do not die when they normally would. These abnormal lymphocytes instead build up, causing swelling of not only the lymph nodes but also potentially the spleen and the liver in later-stage disease.25

There are many different types of lymphoma, but they are divided into two main categories: HL and NHL. The main difference between these two types is the presence or absence of a Reed-Sternberg cell, which is a large, abnormal lymphocyte that may contain more than one nucleus. These multi-nucleated Reed-Sternberg cells are present in HL but not typically found in the many variants of NHL.28

Lymphomas can be further classified into the type of lymphocytes that have become malignant, either B lymphocytes (B-cells) or T lymphocytes (T-cells). Whereas HL occurs due to malignantly transformed B-cells, NHL can be associated with either malignantly transformed B-cells or T-cells.25

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common subtype of NHL, accounting for 30% to 40% of new NHL diagnoses.29 The overwhelming majority of orbital lymphomas are of B-cell origin.30 One type of B-cell NHL is a MALT lymphoma, which tends to affect elderly patients. Due to the lacrimal gland secreting IgA and IgG antibodies via MALT as mentioned above, this is an important consideration when the lacrimal gland is enlarged.25,28,30

Orbital lymphoma, or ocular adnexal lymphoma, is a localized form of systemic lymphoma affecting the orbit, lacrimal gland, eyelids and conjunctiva. Conjunctival involvement can present as a salmon or flesh-colored mass on the conjunctiva.31 Lymphoid orbital tumors comprise 10% to 15% of all orbital tumors and are the most prevalent orbital malignancy affecting older adults.32,33

Although this patient’s clinical presentation could lead to several differential diagnoses, the addition of the history of past lymphoma causes orbital lymphoma to rise to the top of the differential diagnosis list. In this case, due to the history of lymphoma, the first step of the workup was to obtain neuroimaging to assess for cancer risk; an orbital MRI with contrast is preferred if not contraindicated.

Our patient had no contraindications and proceeded with the imaging. The results revealed enlargement and enhancement of the lacrimal gland (Figure 4). The structural abnormality extended temporally and superiorly behind the globe into the orbit, also encompassing the medial rectus and superior rectus muscles.

Subsequent biopsy confirmed B-cell NHL. Because the disease was localized to the orbit, systemic chemotherapy was not indicated, and the patient underwent orbital radiation.34 Treatment options now also include biologics such as CD20 monoclonal antibodies, which can destroy B-cells.35

While the presence of MALT within the lacrimal gland increases the risk for lymphoma, it is important to recognize that not all lacrimal swelling is a tumor and that not all lacrimal gland tumors are lymphomas. In fact, lymphomas are not responsible for the majority of lacrimal gland tumors. Of greater frequency, and the most common malignant histology of the lacrimal gland, are adenoid cystic carcinomas.36 These primary cancers are of epithelial origin and often present with pain related to perineural growth of the cancer.37

Adenoid cystic carcinomas have a poor prognosis, with only a 20% survival rate at 10 years.37 Another important consideration in the differential diagnosis of lacrimal gland tumors is those caused by metastasis from a distant primary cancer. Metastatic tumors of the lacrimal glands are most frequently caused by breast cancer metastases but can certainly be associated with other primary cancers as well.38,39

This case serves as a reminder to always ask your patients about a personal history of cancer. A patient’s history of cancer is an important consideration regardless of the previous area/tissue involved, how remote the condition was or how long the individual has been in remission. It is a good practice assessment to take baseline exophthalmometry readings not only on patients with a history of thyroid disease but also on all patients with a medical history related to cancer so that you can monitor for interval change.

In this particular patient, asking about a previous cancer diagnosis helped to hone in on the correct diagnosis and get him the fastest possible treatment, which in turn can potentially improve the prognosis.

Takeaways

Abnormal lacrimal gland structure, changes to the anatomy and/or variations of function can be suggestive of, and possibly the initial manifestation of, systemic disease. Eyecare providers need to be aware of systemic conditions that can affect the lacrimal gland so that prompt and relevant workup and management can be initiated. Appropriate diagnostic workup, treatment, management and referral of patients with lacrimal gland dysfunction can improve both long-term ocular and systemic prognosis.

Dr. Maglione graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. She completed a two-year advanced residency program at the Eye Institute in neuro-ophthalmic disease. She continues to work in the neuro-ophthalmic disease service at the Eye Institute and teaches didactically in neuroanatomy and neuro-ophthalmic disease courses at Salus University. She has no financial disclosures.

Dr. Malloy is a professor at Salus University, where she specializes in neuro-ophthalmic disease. She is the Chief of the Neuro-Ophthalmic Disease Specialty Clinical Service at the Eye Institute and Co-Director of the Neuro-Ophthalmic Disease residency program at Salus University. She is a Diplomate in this specialty at the American Academy of Optometry. She is a speaker and on the advisory board for Osmotica Pharmaceuticals and RVL Pharmaceuticals.

1. Singh S, Selva D. Non-infectious Dacryoadenitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2022;67(2):353-68. 2. Hibino M, Kondo T. Dacryoadenitis with Ptosis and Diplopia as the Initial Presentation of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Intern Med. 2017;56(19):2649-53. 3. Caçola RL, Alves Morais S, Carvalho R, et al. Bilateral dacryoadenitis as initial presentation of a locally aggressive and unresponsive limited form of orbital granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Reports. 2016;2016:bcr2015214099. 4. Machiele R, Lopez MJ, Czyz CN. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Eye Lacrimal Gland. In: StatPearls. 2022: Treasure Island (FL). 5. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75-92. 6. Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. Sjögren’s syndrome. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:273-85. 7. Huang R, Su C, Fang L, et al. Dry eye syndrome: comprehensive etiologies and recent clinical trials. Int Ophthalmol. 2022;42(10):3253-72. 8. Patel R, Patel BC. Dacryoadenitis. In: StatPearls. 2022, StatPearls Publishing 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL). 9. Mombaerts I. The many facets of dacryoadenitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(5):399-407. 10. Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):669-83. 11. Heinle R, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis. Autoimmun Reviews. 2014;13(4-5):383-7. 12. Sfiniadaki E, Tsiara I, Theodossiadis P, et al. Ocular Manifestations of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: A Review of the Literature. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(2):227-34. 13. Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Cai M, et al. Central Nervous System Involvement in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: What Neurologists Need to Know. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1166. 14. Jordan GA, Beier K. Chalazion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2021, StatPearls Publishing. 15. Leivo T, Koskenmies S, Uusitalo M, et al. IgG4-related disease mimicking chalazion in the upper eyelid with skin manifestations on the trunk. Inter Ophthalmol. 2015;35(4):595-7. 16. Moriyama M, Tanaka A, Maehara T, et al. T helper subsets in Sjögren’s syndrome and IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialoadenitis: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2014;51:81-8. 17. Jakobiec FA, Rashid A, Lane KA, et al. Granulomatous dacryoadenitis in regional enteritis (crohn disease). Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(4):838-844.e1. 18. Linskens RK, Mallant-Hent RC, Groothuismink ZMA, et al. Evaluation of serological markers to differentiate between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: pANCA, ASCA and agglutinating antibodies to anaerobic coccoid rods. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(9):1013-18. 19. Akella SS, Schlachter DM, Black EH, et al., Ophthalmic Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss Syndrome): A Systematic Review of the Literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(1):7-16. 20. Mombaerts I, Bilyk JR, Rose GE, et al. Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria of Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation Using a Modified Delphi Approach. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):769-76. 21. Martínez Díaz M, Piqueras SC, Marchite CB, et al. Acute dacryoadenitis in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Orbit. 2022;41(3):374-7. 22. Obata H, Yamagami S, Saito S, et al. A case of acute dacryoadenitis associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47(1):107-9. 23. Rhem MN, Wilhelmus KR, Jones DB. Epstein-Barr virus dacryoadenitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(3):372-5. 24. Madge SN, Prabhakaran VC, Shome D, et al. Orbital tuberculosis: a review of the literature. Orbit. 2008;27(4):267-77. 25. Singh R, Shaik S, Negi BS, et al., Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(4):1834-40. 26. Ross AM, Leahy CI, Neylon F, et al. Epstein–Barr Virus and the Pathogenesis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Life (Basel). 2023;13(2):521. 27. Lai Y, Shi H, Wang Z, et al. Incidence trends and disparities in Helicobacter pylori related malignancy among US adults, 2000-2019. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1056157. 28. Yadav G, Singh A, Jain M, et al. Reed Sternberg-Like Cells in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Diagnostic Challenge. Discoveries (Craiova). 2022;10(3)e155. 29. Chen Y, Xu J, Meng J, et al. Establishment and evaluation of a nomogram for predicting the survival outcomes of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on International Prognostic Index scores and clinical indicators. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11(2):71. 30. Olsen TG, Heegaard S. Orbital lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(1):45-66. 31. McGrath LA, Ryan DA, Warrier SK, et al. Conjunctival Lymphoma. Eye. 2023;37(5):837-48. 32. Vogele D, Sollmann N, Beck A, et al. Orbital Tumors--Clinical, Radiologic and Histopathologic Correlation. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(10):2376. 33. Chen YQ, Yue ZF, Chen SN, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of orbit: A population-based analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:990538. 34. Pereira-Da Silva MV, Di Nicola ML, Altomare F, et al. Radiation therapy for primary orbital and ocular adnexal lymphoma. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2022;38:15-20. 35. Constantinides M, Fayd’herbe De Maudave A, Potier-Cartereau M, et al. Direct Cell Death Induced by CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies on B Cell Lymphoma Cells Revealed by New Protocols of Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(4):1109. 36. Andreoli MT, Aakalu V, Setabutr P. Epidemiological Trends in Malignant Lacrimal Gland Tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2):279-83. 37. Benali K, Benmessaoud H, Aarab J, et al. Lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma: report of an unusual case with literature review. Radiat Oncol J. 2021;39(2):152-8. 38. Nickelsen MN, VON Holstein S, Hansen AB, et al. Breast carcinoma metastasis to the lacrimal gland: Two case reports. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(2):1031-5. 39. Chen H, Li J, Wang L, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to the lacrimal gland: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(2):911-3. |