|

Exploring the Impact of Lens Coatings on Emotional Connection

This activity is supported by unrestricted educational grant from Shamir.

Faculty: Ramin Rabbani, OD, and Carissa Dunphy, ABOC

Release Date: March 15, 2023

Expiration Date: March 15, 2024

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: 2 hours

Goal Statement: This course will explore the impact of lens coatings on emotional connection.

Educational Objectives:

Explore the impact of lens coatings and its effects on patients.

Examine the connection between eye strain and light wavelengths and their connection to mental health.

Review various studies that look at ophthalmic lenses, mental health, and lens coatings.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists who provide primary care optometry services, including but not limited to medical optometric services.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Ramin Rabbani, OD, and Carissa Dunphy, ABOC

Continuing Education Credit: This activity, COPE Activity Number(s) 82320-GO is accredited by COPE for continuing education for optometrists.

Reviewed by: COPE

Administered by: Review Education Group

Distributed by: Review of Optometry

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: Review Education Group (REG) requires faculty, planners, and others in control of educational content to disclose all their financial relationships with ineligible companies. All identified conflicts of interest (COI) are thoroughly mitigated according to PIM policy. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high quality accredited continuing education activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in healthcare and not a specific proprietary business interest of an ineligible company.

Carissa Dunphy, ABOC: No financial disclosures.

Ramin Rabbani, OD: No financial disclosures.

Planners and Managers: REG planners and managers have nothing to disclose.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. The planners of this activity do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the planners. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient’s conditions and possible contraindications and/or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

|

Two top priorities that patients have when they select eyewear is how they see and how they look. This, in turn, affects how patients function and feel. However, there is a natural tendency to attribute looks and feelings exclusively to frames, when in fact lens properties play a significant role in the total wearer experience. Similarly, we don’t often appreciate the multidimensional benefits of high-quality lenses. For example, improved eyesight can reduce eyestrain, improve comfort, and increase productivity. Consider too how vision can help patients feel more relaxed, secure and confident navigating the world around them.

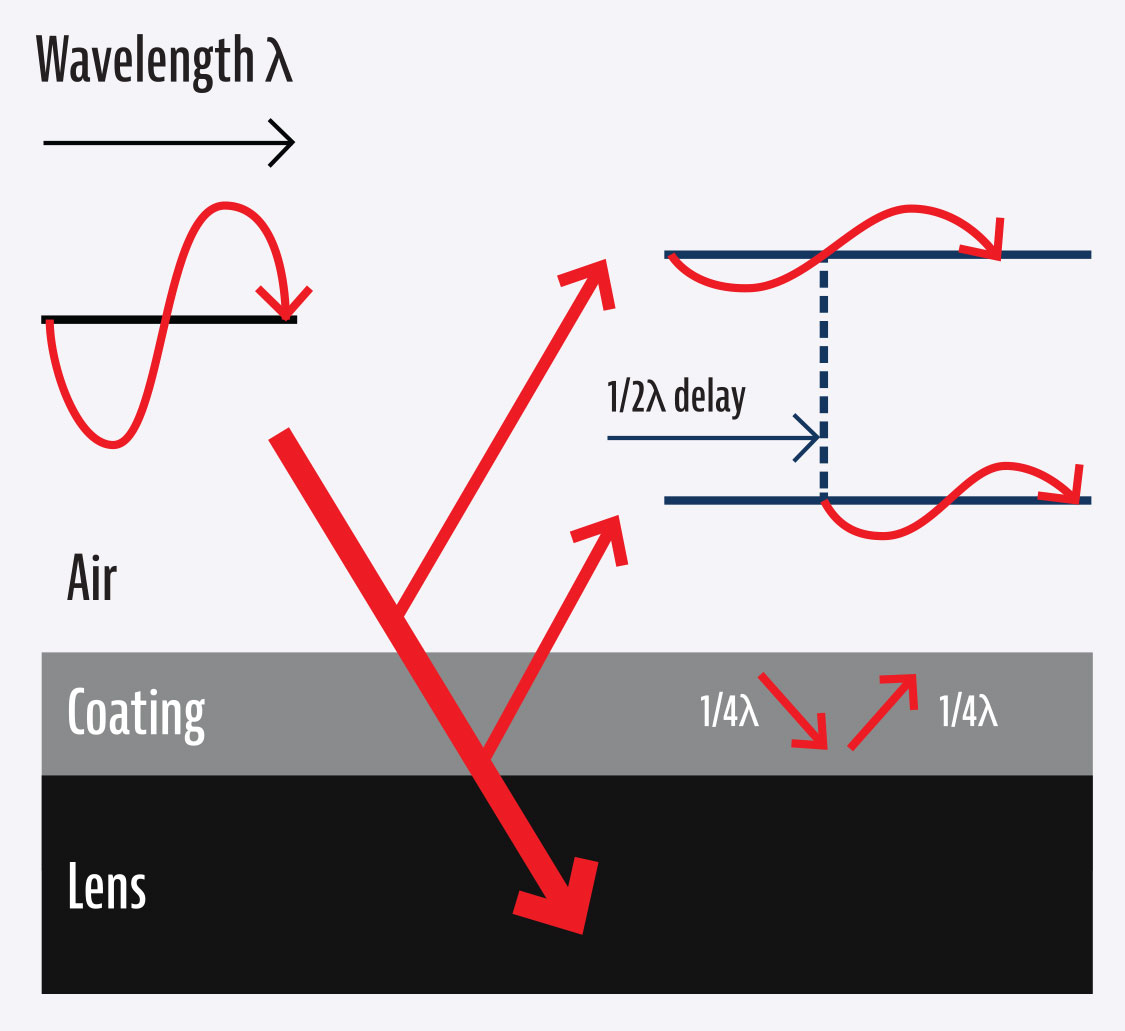

Another consideration is that lenses don’t only impact how patients see—they also affect how they are seen. Reflections have always been considered aversive, but now they’re much more obvious because we can see them on Zoom and on images of ourselves on social media. Early research that emerged as our dependence on digital devices increased has expanded dramatically. Our initial focus was on eye strain and light wavelengths and how all of this impacts our overall physical wellbeing. But the immediate shift to digital face-to-face interaction has brought new concerns to light. As we are now recognizing, lens selection can also play a role in emotional wellbeing. In the pages that follow, we’ll review the evolution of this emerging research and discuss the implications when making a lens recommendation.

Human Connection 101

For better or worse, we worry a lot about the impressions we make on others. Although these evolve over time, first impressions are formed very quicky. In fact, research shows that first impressions begin to form within one-tenth of a second, 2 and quite a lot happens in the span of seven seconds. That might sound rather immediate but the subconscious mind operates quickly. For example, our brains are rapidly judging trustworthiness and other traits that, from an evolutionary standpoint, were once relevant to human survival. Indeed, first impressions are yet another example of how survival of the fittest has played out since the dawn of time. Although our needs may be different now than they once were, our ability to assess other humans is no less important today than it was thousands of years ago.

We assess people all the time. What was once a way to ensure personal safety is now a mechanism to excel socially, build stronger support networks, and succeed in business. All of this circles back to our ability to form first impressions. Of course, first impressions aren’t everything, but they exert a strong influence. In fact, in a series of experiments conducted by Princeton psychologists, scientists determined that looking at a stranger’s face for longer than 100 milliseconds merely boosts one’s confidence in their judgements rather than significantly altering those first impressions.2

First impressions are based largely on facial expressions. More than 100 years ago, Charles Darwin justified the theory of evolution by natural selection with the controversial argument that human facial expression is a sort of universal language.3 Since then, hundreds of follow-up studies have been generated on this same topic, with recent investigations demonstrating universality despite cultural and demographic diversity, even in online contexts. 3

|

When you think back to a more primitive era, it seems logical that showing one’s teeth might be used to establish dominance whereas a smile can have a very different effect. In either case, these are messages that transcend time and place. But many facial expressions are more subtle than a scowl or a frown. Humans have 43 muscles in the face and they work together to create thousands of expressions, often using the muscles around the eyes to convey messages. Consider how smiles differ depending on whether they involve the eye area. Impressions about whether a smile is genuine are often based on whether you notice crow’s feet around the eyes. We may assume that a smile is forced or lacks feeling when we don’t see it in someone’s eyes. We make these judgements automatically, and without formal training, in a tenth of a second because, as Darwin would assert, that is how we’re programmed.

Researchers at UC Berkeley and Google used machine learning technology to analyze facial expressions in 6 million YouTube video clips from people in 144 different countries. 3 Remarkably, this research showed that across these many different countries and cultures, at least 70% of the same facial expressions are shared and used in response to particular social and emotional situations. 3 These findings imply a universality of human expression that transcends geographic and cultural boundaries even in an online context. 3

|

Studying Modern Connection

Although digital interaction has been on the rise for many years, when COVID hit there was a seismic shift in how we routinely connect with others and it’s persisted despite businesses opening back up. Audio-only conference calls are out and video communication is here to stay. Indeed, many Americans have largely transitioned from in-person interactions to meeting, working, and socializing over digital platforms. As such, it has become more important than ever to find ways to trust and connect with people in this new on-screen environment. However, digital environments are such that we have other variables to contend with including pixel density, screen dimensions, Wi-Fi strength, lighting, reflection, and audio or video lags. Also, consider that we can only see about 15% of an interactant’s body on screen — sometimes even less or at smaller dimensions depending on how screens are being shared. Understandably, connections are harder to establish and maintain on digital mediums.

A recent pair of studies sought to determine whether different lens coatings affect how people see others when they’re meeting strangers in creating first impressions. Two experiments were designed to determine whether, for example, people respond differently or perceive others differently based on lens clarity.

|

Study 1

In the first experiment, researchers hypothesized that the better you can see someone’s eyes when meeting them for the first time, the better you’ll be able to read their emotions and gauge their intent, which in turn will positively impact the first impression. Positive first impressions are characterized by how connected you feel, how you perceive the stranger’s trustworthiness and likability, and whether your connection elicits empathy. The following research questions were posed:

CONNECTION - Do anti-glare coatings impact a viewer’s sense of connection?

TRUST - Do anti-glare coatings impact a viewer’s perception of trustworthiness?

LIKABILITY - Do anti-glare coatings impact a viewer’s perception of likability?

EMPATHY - Do anti-glare coatings impact a viewer’s sense of empathy?

CONFOUNDING - Do any confounding variables potentially affect participant responses and synthesized findings?

The study was conducted online using video recordings of actors wearing lenses with Glacier PLUS coating, Glacier Expression coating, or lenses without any anti-glare coating. In all three scenarios, actors wore understated frames. Participants included 1288 men and women between the ages of 18 and 99. The sample was geographically balanced with incomes skewed to reflect US census data.

|

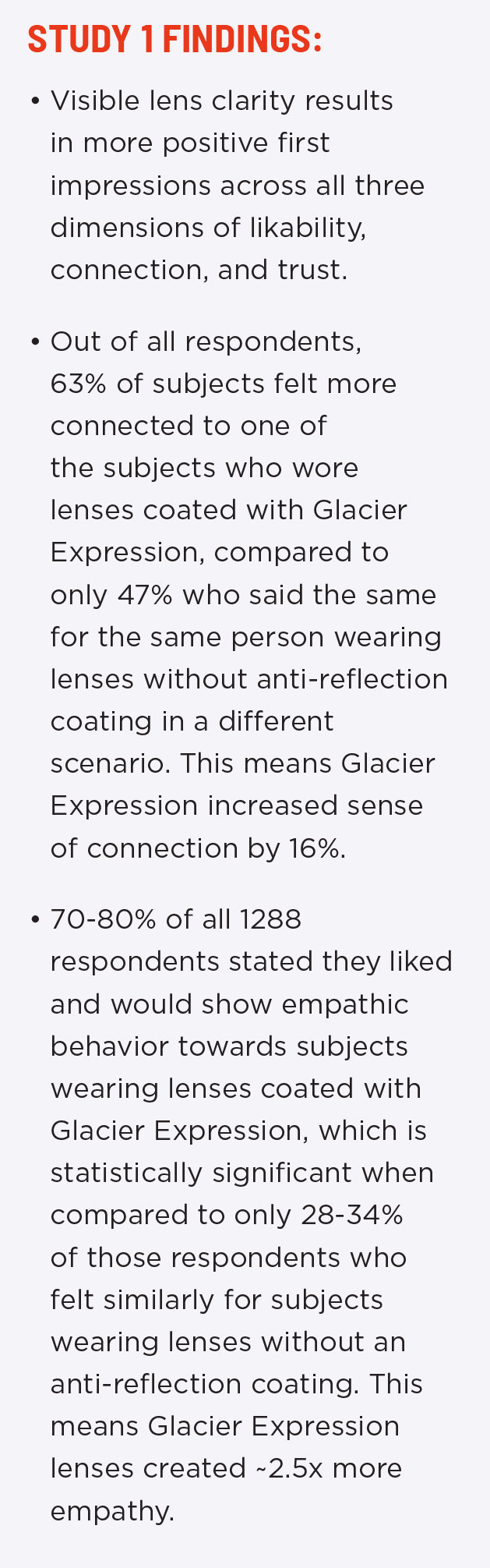

Results of the study 1 experiment reveal that clearer lens clarity results in more positive first impressions across all three dimensions (likability, connection, and trust). Out of all respondents, 63% of subjects felt more connected to one of the subjects wearing lenses with Glacier Expression coating, compared to only 47% who said the same for the same person wearing lenses without anti-reflection coating in a different scenario. In other words, Glacier Expression increased a sense of connection by 16%. In addition, 70-80% of all respondents stated they liked and would show empathic behavior towards subjects wearing Glacier Expression, which is statistically significant when compared to only 28-34% of those respondents who felt similarly for subjects wearing lenses without an anti-reflection coating. This means the anti-glare coated lenses created ~2.5x more empathy. Participants were also given the option to select from 20 positive and negative adjectives to describe subjects wearing lenses with an anti-glare coating. In this arm of the experiment, respondents consistently associated positive adjectives with those who wore lenses treated with an anti-glare coating. Furthermore, the adjective “trustworthy” consistently topped the list of adjectives. (See Study 1 Findings).

Study 2

Although impacts of lens coatings were evident in the study 1 research findings, researchers wanted to see if there was a significant difference between the current high-end lens coatings and Glacier Expression lenses. Furthermore, they wanted to determine whether clarity would be amplified if people were meeting in person versus online. Their research questions included:

|

ENVIRONMENT - Are impacts of lens clarity on impression more significant in person compared to digitally over video?

CONNECTION - Is lens clarity directly correlated with connection? Do clearer lenses make viewers feel more connected to the person wearing the glasses?

TRUST - Is lens clarity directly correlated with trustworthiness? Do people trust people wearing clearer lenses more than those who don’t?

CONFOUNDING - Do any confounding variables potentially affect participant responses and synthesized findings?

VISIBILITY - Do the different lens coatings impact how the wearers feel and see?

In sum, 40 participants were recruited from coffee shops in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As in the previous study, the sample was gender balanced. Study 2 was unique in that participants engaged in a hands-on activity. They were asked to try on a pair of glasses with lenses coated with Glacier Expression and a pair of glasses coated with Glacier Plus. Researchers then formally gathered feedback on how people feel and see the world when they wear glasses of varying lens coating qualities.

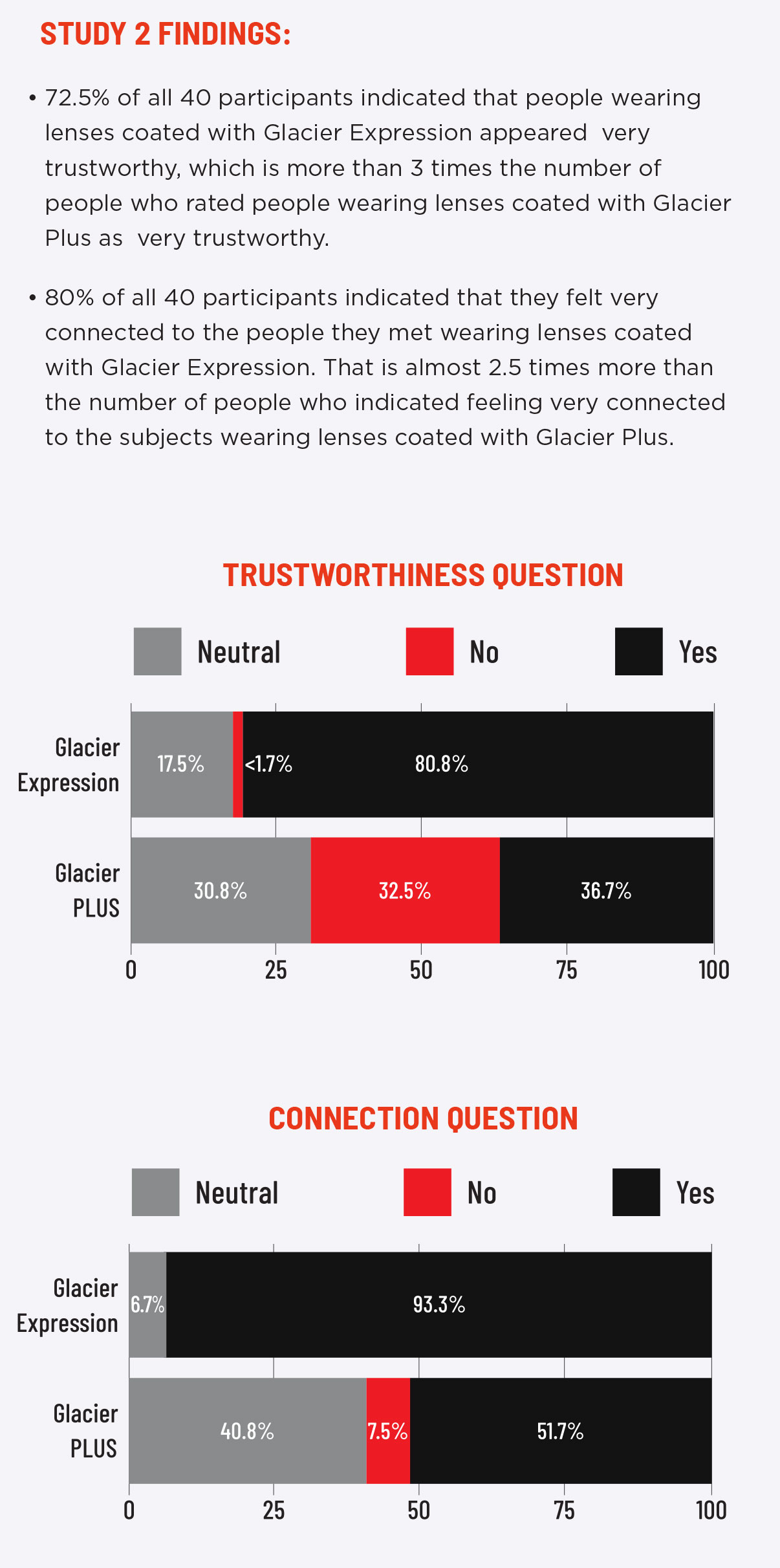

One of the key takeaways is that researchers found a direct correlation between clarity and positive impressions. Specifically, participants perceived more trustworthiness and a higher sense of connection to the people who were wearing lenses coated with Glacier Expression compared to those wearing lenses with Glacier Plus—and this was true regardless of whether the person wearing those glasses was male, female, had dark eyes, light eyes, or was the first or the second person that they met in the research session (See Study 2 Findings).

In short, consistent with evolutionary psychology theories, data shows that the better someone can see our eyes and determine our genuine emotion, the more trustworthy we appear, the more likeable we become, and the easier it is for people to connect with us.

There is a lot of data from this and other research experiments that suggest what characteristics or behaviors can contribute to increased connection and positive first impressions. There are things that we can and some things that we cannot control that contribute to those sentiments and judgements. Lens clarity is one of the easiest and most affordable ways, proven with both rounds of this research, to positively impact the sense of connection between people and positive first impressions.

|

Implications

We take for granted that we feel more connected to people when we can see their eyes, but we don’t always consider how online interaction inteferes with this fundamental component of interpersonal communication. Many of our patients spend 6, 8, or even 10 hours per day in front of the computer screen, which is visually demanding and very different from office working conditions. Working from home is very different. For example, often, most home environments are not optimized for heavy screen time, with light coming in from all directions. Glare is a barrier to connection.

We also usually view others on a smaller scale on-screen. In some cases, we can barely see the eye of the person we’re talking with, much less read the eyes’ expressions the way we can in person. In short, there’s a lot of visual noise and a lack of clarity inherent in most digital environments, presenting a unique new challenge that ophthalmic lens manufacturers must aspire to overcome. In turn, as eye care providers, we need to be sensitive to these new visual and emotional demands so we can help alleviate our patients’ struggles.

|

1. Rosenberg M, Luetke M, Hensel D, Kianersi S, Fu TC, Herbenick D. Depression and loneliness during April 2020 COVID-19 restrictions in the United States, and their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(7):1221-1232. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-02002-8 2. Todorov, A. (2017). Face value: The irresistible influence of first impressions. Princeton University Press. 3. Cowen, A.S., Keltner, D., Schroff, F. et al. Sixteen facial expressions occur in similar contexts worldwide. Nature 589, 251–257 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3037-7 4. Jalie M. Ophthalmic lenses & dispensing. Butterworth-Heinemann. 1999; Chapter 15, p: 180-181. 5. Yao X, Ji B, Li M, Men Y, Jin X, “Research on the Impact of Road Landscape Color on the Driving Fatigue of Drivers”, IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 440 (2020). 6. Kara-Junior N., Safady M., José NK. Dissatisfaction with glasses. Rev Bras Oftalmol.; 2020; 79 (6): 416-9. |