Don't Be Stumped by These Lumps and Bumps

Most eyelid lesions are benign, but some can lead to severe clinical outcomes if not caught early.

By Rodney Bendure, OD, and Jackie Burress, OD

Release Date:

April 2017

Expiration Date:

April 15, 2020

Goal Statement:

Although the majority of lesions present on the eyelids are benign, the identification and diagnosis of lesions that are cause for concern are imperative to avoid adverse clinical outcomes. This course provides a comprehensive overview of the identification of eyelid lesions and the treatment options for each.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Rodney Bendure, OD, and Jackie Burress, OD

Credit Statement:

This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Course ID is 53201-AS. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statement:

Authors: The authors have no relationships to disclose.

Peer Reviewers: The reviewers have no relationships to disclose.

Editorial staff: Jack Persico, Rebecca Hepp, William Kekevian, Michael Riviello and Michael Iannucci all have no relationships to disclose.

Learn the Lingo |

| With all the terms used to describe neoplasms, it’s not surprising that a lot of clinicians get lost in the milieu. Brush up on these terms: Neoplasm: A new growth. Essentially, this term grossly defines a mass of tissue that has outgrown the surrounding tissues. Tumor: A general medical term historically used to describe any area of swollen tissue, including those caused by inflammation, hemorrhage or edema. This term is often used interchangeably with neoplasm, though its connotation may be worse. Benign: Neoplasms that have been deemed relatively innocent by clinical and microscopic evaluation, and are unlikely to spread to other sites. These can be excised and carry a good prognosis, although they can cause local tissue destruction if left untreated. Malignant: All malignancies are cancers. All cancers are malignancies. However, all tumors and neoplasms are not cancers or malignancies. To use the term malignant or cancer means that the lesion has tendency to spread to and undermine neighboring tissues as well as to metastasize (spread to distant sites). Therefore, malignant tumors carry the potential for early mortality. Cancer: A malignant neoplasm. Adenoma: Benign epithelial neoplasm derived from a gland. Papilloma: Benign epithelial neoplasm which produces finger-like fronds. Carcinoma: Malignant neoplasm derived from epithelial cells (any epithelial cell, not just skin). Squamous cell carcinoma: A carcinoma (malignant neoplasm), derived from stratified squamous epithelium. Adenocarcinoma: A malignant lesion comprised of epithelial cells (carcinoma), which grow in a glandular pattern (adeno). Hamartoma: A mass of disorganized tissue comprised of cells native to the host organ. An example would be an iris Lisch nodule composed of melanocytes. Choristoma: A congenital, benign mass of normal tissue located in non-native tissue. An example would be a limbal dermoid containing fat, connective tissue and epidermal appendages. |

The vast majority of eyelid lesions encountered in the typical optometry practice are benign.1 However, it is important clinicians are able to identify lesions capable of infiltration, tissue destruction and metastasis. To start, clinicians must appreciate the basic anatomy of the eyelid. At only 0.7mm to 0.8mm, the eyelid is the thinnest skin on the human body.2 Yet, it contains all the components of skin on other areas except a layer of subcutaneous fat. Beginning externally and working posteriorly, we first encounter the epidermis, which contains several layers of cells including keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells and Merkel cells. Commencing at the melanin-containing basal cell layer, epithelial cells differentiate and migrate toward the skin surface, eventually losing their melanin granules, flattening and producing keratin. The underlying dermis is comprised of connective tissue, nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics. Deeper, you will find the orbicularis muscle and tarsal plate. Finally, the palpebral conjunctiva covers the posterior surface of the eyelid, abutting the globe. Adnexal structures, including glands and hair follicles, are located in the dermis and tarsal plate.1

| |

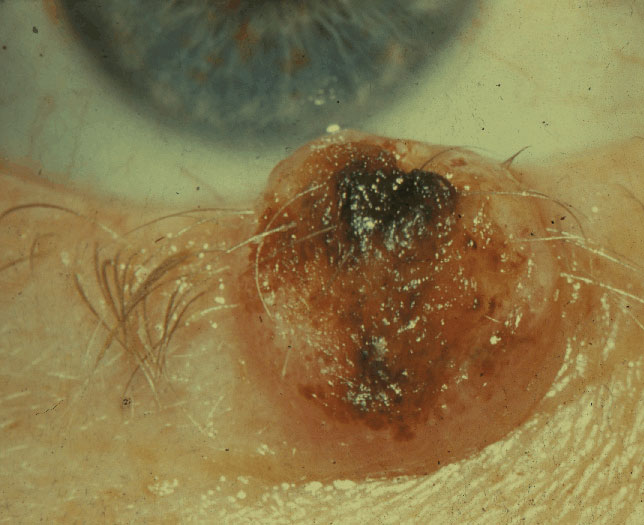

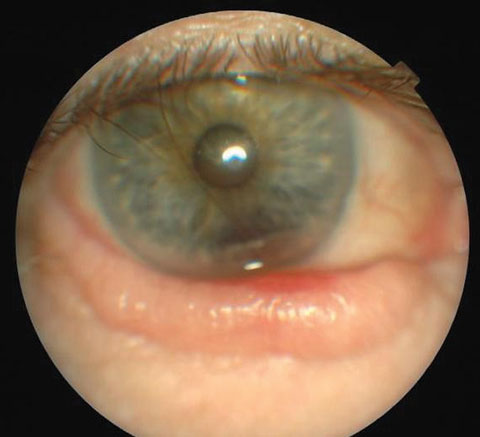

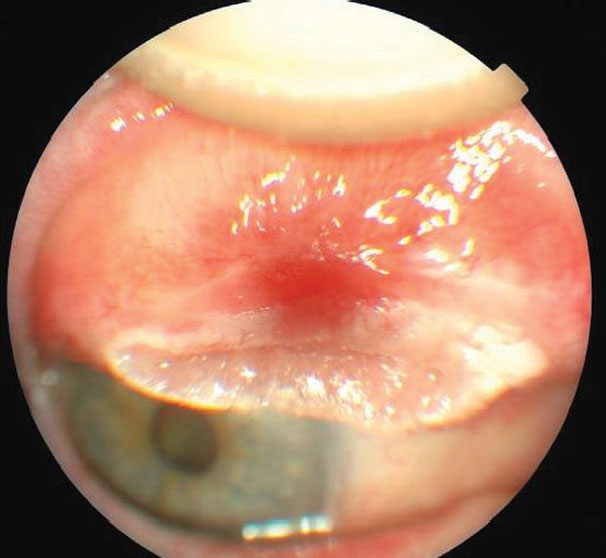

| Presented here is an advanced infiltrating eyelid malignancy. Click image to enlarge. | |

| |

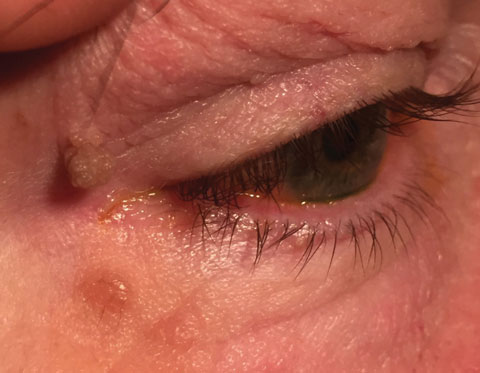

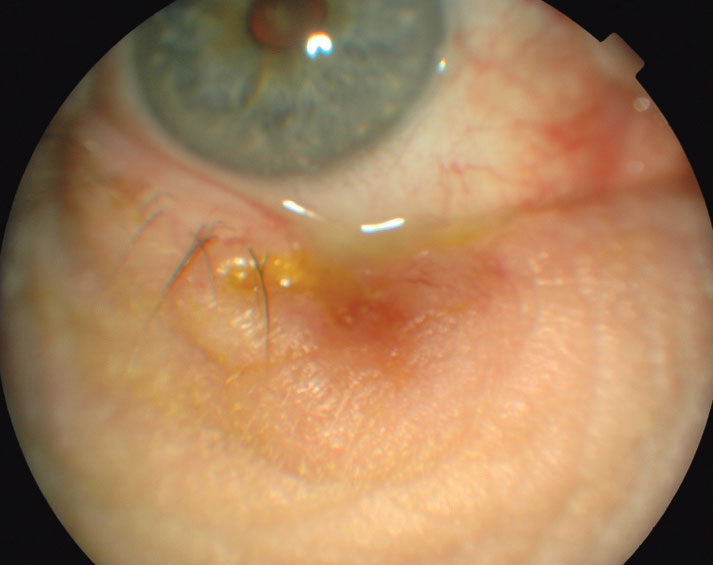

| This superior lesion is a typical squamous papilloma. The inferior lesion is a junctional nevus. Click image to enlarge. | |

| |

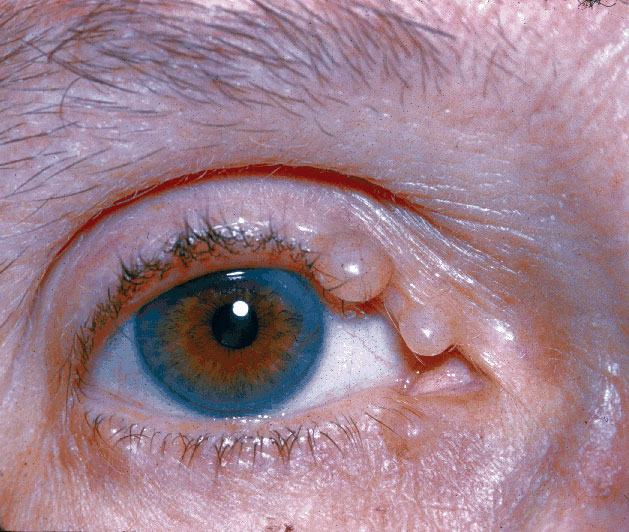

| An example of advanced seborrheic keratosis. Click image to enlarge. |

Physical Characteristics

Specialists use a number of terms to describe the presentation of a particular lesion. Knowing these terms will help clinicians better classify and more accurately convey lesion characteristics to the pathologist. First, the term tumor does not necessarily describe a cancer. Rather, it is a general term for an area of swollen tissue. Neoplasia, likewise, is a general term describing the abnormal growth of tissue, be it benign (noninvasive) or malignant (likely to spread aggressively and metastasize).3 Ulceration refers to a loss of epithelial tissue. Hyperkeratosis indicates the increased production of keratin, often noted clinically as scaling. Induration is seen as redness and swelling of a lesion. Crusting is dried exudate on the skin surface.1

At the microscopic level, the pathologist may describe atypia, or an abnormality of an individual cell, whereas dysplasia denotes a change in the size, shape and organization of the cellular structure of a tissue.1

Clinically, a number of additional terms are used to describe the shape and consistency of a lesion to help differentiate the etiology. A cyst is a nodule lined with epithelial tissue and filled with a material that is fluid to near solid in consistency. Bullae are large, fluid-filled cysts. Pustules are smaller cysts less than a centimeter in size. Vesicles are even smaller fluid-filled cysts, generally less than half a centimeter in diameter.1

Macule refers to an area of flat epidermal tissue, usually less than a centimeter across, with color change only. Examples are freckles and vitiligo. Plaques are similar, but larger (2cm or more) and slightly elevated. A papule is a solid lump less than a centimeter in size. Nodules are essentially just larger papules.1

Examination

A thorough lesion exam always begins with a detailed history. The patient should be queried regarding UV exposure, smoking, immunosuppression and history of cancer and radiation therapy. Lesion-specific questions such as the length of symptoms, rate of growth, bleeding, ulceration, color changes and alteration of tissue such as loss of lashes should be addressed.

During the exam, clinicians should document a detailed description of each lesion's characteristics. In particular, record lesion size, location, pigmentation, ulceration, loss of normal eyelid architecture and consistency—whether fleshy or firm, freely mobile or affixed to underlying tissues. Take time to palpate the lesion to assess these characteristics. Photographs are also an important part of your documentation. External photography can be accomplished using a slit lamp camera, fundus camera with anterior segment features or a smart device. It is especially helpful to have a metric ruler near the lesion for reference. A photography tip—don’t use excessive illumination, as it can wash out the lesion.

Tumor Classification

Eyelid tumors, like neoplasms in other areas of the body, are classified by their cell origin. Many clinicians find it useful to categorize eyelid lesions as either inflammatory (e.g., chalazion), infectious (e.g., hordeolum) or neoplastic. Neoplasms can further be described by their oncogenic potential, whether benign, premalignant or malignant.

ABCs of Skin Lesions |

| While no hard and fast rules exist, certain characteristics provide clinicians with clues as to the nature of skin neoplasms. These rules, easily remembered using the mnemonic ABCDE are described in detail here: Asymmetry: If you draw a line through a benign lesion, both halves are typically symmetrical. Borders: Benign lesions have regular borders. Color: Variations in color in a single lesion raise suspicion of malignancy. Diameter: Lesions larger than 6mm diameter are suspicious of malignancy. Evolution: Growth, bleeding, crusting, loss of lashes or changes in color increase suspicion of malignancy. |

Benign Tumors

Benign lid lesions are by far the most prevalent form of neoplasms seen in eye care, accounting for more than 80% of lid lesions.8 Epithelial tumors are the most common type of eyelid neoplasms; these include papillomas, seborrheic keratoses, inclusion cysts and many more.9 A thorough history and examination of the lid lesion can often result in accurate diagnosis.

Squamous papilloma. Far and away the most common benign epithelial eyelid tumor, this arises as an excessive growth of the squamous epithelium. It is characterized as either a sessile (flat) or pedunculated (skin tag) growth with an oft-keratinized surface. This slow-growing tumor is common in middle-aged and elderly patients and often presents as multiple lesions. Squamous papilloma is treated by simple excision at the lesion base, cryotherapy, or laser or chemical ablation. Prognosis is excellent, though patients often develop additional papillomas with age.1,10

Seborrheic keratosis. This is another very common slow-growing, benign epithelial tumor. It is typically described as having a greasy, “stuck-on” appearance. Affecting middle-aged and elderly individuals, these benign lesions are well-demarcated, elevated plaques with variable levels of pigmentation. They tend to enlarge and darken gradually over time. Excision with electrocautery or cryotherapy will generally eliminate recurrence. Prognosis is excellent.1,10 However, a sudden increase in the size or number of lesions can occur in individuals with occult malignancies and should therefore raise suspicion.11

Cutaneous horns. These are somewhat non-specific hyperkeratotic lesions, which may be associated with a variety of both benign and malignant eyelid lesions, including seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Thus, this is a clinically descriptive term and not a specific lesion type. Treatment is excision requiring pathologic evaluation.10 Because the horn is an extension of an undetermined underlying tumor, biopsy requires excision of epidermal tissue beneath the lesion as well.11

Epidermal inclusion cysts. These arise from entrapment (usually traumatic) of epidermal tissue within the dermis. They appear as discrete white or light yellow, firm, solid, slow-growing cysts. Treatment is by excision, though the entire cyst wall must be removed to prevent recurrence. Prognosis is excellent.10,11

|  |  |

| This is a typical lesion seen with molluscum contagiosum. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cogan Collection, NEI/NIH | Shown here is an epidermal inclusion cyst. Click image to enlarge. | Shown here is an example of an xanthelasma. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cogan Collection, NEI/NIH |

Molluscum contagiosum. A poxvirus infection, this is characterized by small, typically 1mm to 2mm, flesh-colored papules with an often-umbilicated center. These are more common in the very young and the immunocompromised. Lid margin lesions can cause a follicular conjunctivitis. These lesions are spread by skin-to-skin contact and regress spontaneously except in the immunocompromised, where they can develop into disfiguring lesions. Molluscum contagiosum can be removed if desired by excision, curettage, electrodesiccation or cryotherapy. The prognosis is good in healthy people, and the risk of transmission is low.1,10

Verruca vulgaris. Also known as a viral wart, this is an epidermal growth caused by the human papilloma virus, typically types VI or XI. Two forms exist: filiform, which are also called digitate because they project in a finger-like fashion from their base, and plana, which are flat. Beginning as small papules slightly lighter than the surrounding skin, they tend to darken and become hyperkeratotic with time. While benign, eyelid margin warts can cause punctate keratitis or even corneal pannus.12 Observation is often adequate, as these lesions tend to eventually outgrow their blood supply and spontaneously involute, but may be removed by excision, cryotherapy or chemical cautery if eye irritation ensues or for cosmetic reasons.13

Xanthelasma. This usually presents on the eyelids as yellow plaques filled with lipid-laden macrophages. These arise after the age of 50 and should prompt suspicion of a lipoprotein disorder when present in patients younger than this.1,10 Excision, electrodissection, laser treatment and application of trichloroacetic acid all may be employed with excellent results. However, the lesions tend to recur about 50% of the time.1,10

Syringoma. This benign adnexal tumor appears in multiple, discrete, skin-colored lesions measuring from 1mm to 2mm on the lower eyelids and cheeks of some females beginning in puberty. Heredity appears to play some role in the development of this condition. These lesions are benign adenomas of eccrine ducts. Prognosis is good, although numerous excisions or electrocautery sessions may be required due to the number of lesions; recurrence is common.1,10

Excisional Biopsy Protocols | ||

Lesions with clearly benign characteristics (e.g., squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris) can be excised in office and should be sent for pathologic confirmation. Benign lesions are characterized by even coloration, well-defined regular borders, lack of ulceration, no induration, a history of slow growth and a maintenance of normal skin structures such as lashes and glands.1 Minor surgical procedures to remove such lesions can be performed by optometrists in Oklahoma, Kentucky, Louisiana and Tennessee.4-7 Here’s how to perform an excisional lesion removal:

Benign lesion removal. To excise a benign lesion, you’ll need a 3mL syringe with a one-half inch 27- or 30-gauge needle to inject a small amount of 1% to 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 at the base of the lesion; we often find patients tolerate simple excision without anesthesia, especially for pedunculated masses. Just prior to anesthetizing the base, the area should be sterilized with an ophthalmic betadine swab. Once the area is numb, the mass is grasped with toothed forceps, pulled slightly away from its base and snipped free. Light pressure for a few minutes with a small gauze pad usually stops any bleeding, but a disposable thermal cautery unit comes in handy in case bleeding continues. Place the specimen in a formalin container suitable for transport to the laboratory for histologic evaluation. Prior to releasing the patient, apply a prophylactic antibiotic ointment such as erythromycin or Polysporin and advise the patient to keep the area clean and dry and to apply the ointment three times daily for three days. Malignant lesion removal. Lesions suspicious for malignancy should be promptly referred to an oculoplastics specialist for evaluation, biopsy and reconstruction if needed. Patients may be apprehensive as to what they can expect when referred for lesion removal. It is incumbent upon the referring practitioner to be familiar with the possible treatment techniques to allay any fears the patient may have. A number of alternative methods may be employed for the removal or destruction of eyelid tumors, including chemotherapy, radiation or photodynamic therapy.1,10 However, in our experience complete excisional biopsy is far and away the most common treatment method used by our oculoplastics specialists. For large or aggressive lesions, the preferred method for removal is under frozen section, namely Mohs micrographic surgery.19,26,27 This procedure is particularly useful in periocular cutaneous tumor removal because it causes the least collateral tissue damage while ensuring complete tumor excision.19,26-28 In addition, Mohs procedure has a nearly 100% success rate (97.5% overall, 99.4% for primary lesions and 92.4% for recurrent lesions).19,29,30 Mohs surgery works especially well with basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma because these types of tumors have a continuous growth pattern as opposed to tumor types with “skip areas” such as sebaceous adenocarcinomas.19 Eyelid repair and reconstruction. Repair of the involved eyelid requires special techniques. If less than one-third of the full thickness of the eyelid is removed, a simple direct closure may be performed. For larger defects, more elaborate lid reconstruction procedures using tissues harvested from adjacent areas may be needed.1 |

|

| Seen here are hydrocystomas. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cogan Collection, NEI/NIH |

|

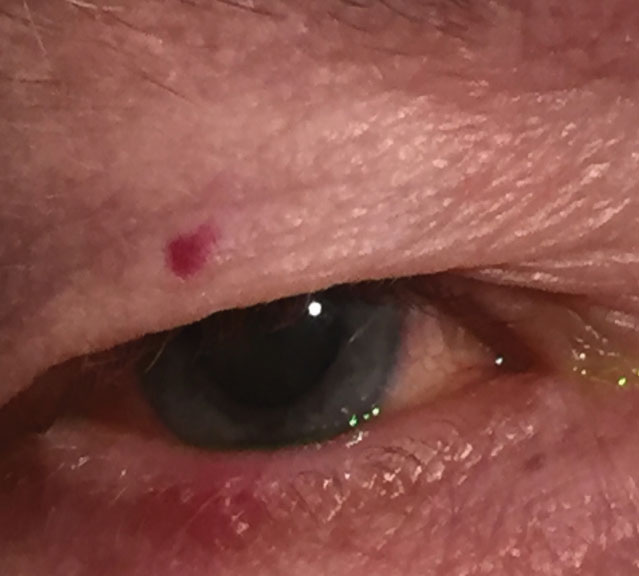

| A hemangioma is present on the upper eyelid. Click image to enlarge. |

|

| Seen here is an example of keratoacanthoma. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cogan Collection, NEI/NIH |

Eccrine hydrocystomas. Also known as sudoriferous cysts, these arise from sweat glands along the eyelid margin. These fluid-filled cysts appear translucent, though thicker-skinned lesions may appear bluish. They may be treated by cyst drainage, but sometimes require removal of the entire cyst wall if recurrent.10,11

Apocrine hydrocystomas. Commonly called cystoadenomas, these resemble sudoriferous cysts except their contents are creamy white. Treatment is by excision.11

Pilomatricoma. This arises from the germinal matrix of a hair bulb and is thus another adnexal tumor. This benign tumor is more common in young females.1 It presents as a hard, indurated nodule. The body reacts in granulomatous fashion due to calcium deposition. Excision is the treatment of choice.1

Trichoepithelioma. This is noteworthy because its appearance is sometimes confused with basal cell carcinoma. These lesions are more common in males, usually arising during puberty.10,14,15 These small skin-colored tumors are benign skin appendage growths. Treatment is by excision. Since these cannot be clinically differentiated from basal cell carcinoma by physical examination alone, pathologic and immunohistochemical evaluation is warranted.10,14,15

Freckles or ephelis. These are small, flat brown skin lesions appearing most commonly on sun-exposed skin, including the eyelids. These are merely a hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer, with no further penetration into the epidermis or dermis. These may lighten in the absence of sun exposure and darken upon re-exposure. The prognosis with these lesions is very good.1,9 No treatment is necessary, although avoidance of ultraviolet light and use of sunscreen can reduce pigmentation.11

Nevi. These are small macules of hyperpigmented melanocytic cells located in the deep epidermis or dermis. These acquired lesions arise in childhood and reach full size by adulthood, darken upon ultraviolet light exposure and tend to involute by the sixth decade.1,10 In adults, they tend to be asymptomatic and stable in appearance. These lesions tend to be one of three main types:1,10

• Junctional nevi are round, flat and less than 1cm in diameter. Usually, these are tan to brown in color and have regular borders.

• Compound nevi are elevated, round, dark brown lesions, which often have hair growing in them.

• Dermal nevi are elevated nodules with variable pigmentation, sometimes skin-colored. These do not tend to involute with age.1,10

Nevi carry a relatively good prognosis with a low potential for malignant transformation.1,16,17 In fact, the annual rates of transformation of a melanocytic nevus are only one in 200,000 for younger individuals and one in 33,000 for the elderly.18 Changes in size, color, irregular borders or bleeding are indications for histologic biopsy.1,10

Milia. These are small superficial white papules 1mm to 4mm in size. They represent keratin-filled piloesebaceous units. Causes include idiopathic, trauma, infection, radiotherapy or bulbous diseases. Treatment is by expression, electro-dessication or excision.1,11

Hemanigiomas. These are elevated red lesions comprised of blood vessels. Three types of these vascular tumors exist, two being congenital and the other acquired:

• Capillary hemangiomas, often referred to as strawberry nevi, are one of the most common tumors in infancy. These are known to blanch with pressure and swell with crying.1,10

• Cavernous hemangiomas, also seen in infancy, are located deeper in dermal tissues. However, these do not blanch with pressure or swell with crying.1,10 Both congenital forms tend to resolve spontaneously over time.

• Cherry hemangiomas can arise rapidly in middle age and older, but are typically associated with similar lesions on other body parts. They carry an excellent prognosis and can be excised for cosmetic reasons.1,10

Pyogenic granuloma. In spite of its name, it is neither pyogenic nor a granuloma and presents in the form of a pinkish red mass that arises after trauma or surgery. These rapidly growing, delicate lesions are comprised of blood vessels and fibroblasts and readily bleed with minor insult. Treatment is by complete excision.11

Pre-Malignant Tumors

Some lesions are precursors to malignant lesions. These must be monitored closely and referred if signs of malignant transformation occur.

Keratoacanthoma. This presents as a dome-shaped nodule with a keratin-filled core on the sun-exposed skin of individuals over the age of 50.10,11 It usually develops rapidly over weeks, only to regress spontaneously after a few months.10 Those with fair skin, chronic sun exposure and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy are at risk for keratoacanthoma.1 Some argument exists as to whether these may represent some variation of squamous cell carcinoma. These tend to be more common in males, with a 2:1 predilection. Treatment is by Mohs surgery with pathologic laboratory evaluation. This lesion carries a generally good prognosis.10 Presence of multiple neoplasms may signify underlying systemic cancer.11

Actinic Keratosis. Formerly known as solar keratosis, this is a slow growing precancerous cutaneous lesion. Occurring on sun-exposed areas of the skin, including the eyelids, these may be caused by ultraviolet radiation. They are common in fair-skinned individuals and are most often noted on the backs of the hands and forehead. These solitary or small-grouped, flat, scaly plaques may occasionally transform into squamous cell carcinoma, though when they do, they are typically low-grade (i.e., they have low mitotic activity).1,10 There is some disagreement in the literature about the likelihood of malignant transformation, with research suggesting risks from 0.1% to 20%, depending on the literature.10,11

Lentigo Maligna. Believed to be caused by sun exposure, these flat brown-to-black macules occur in older individuals, with a median age of occurrence at 65.1,10 Their appearance has been described as looking like a stain on the skin.10 Slow growth and irregular borders are typical. Nodular thickening and variations in color suggest malignant transformation. They should be excised and sent for pathologic laboratory evaluation. Prognosis is excellent so long as they are excised prior to transformation into melanoma.1,10

Malignant Tumors

While malignant tumors are seen much less frequently than benign neoplasms, it is imperative to quickly recognize the lesions that warrant prompt medical intervention. Here we discuss the eyelid malignancies clinicians are most likely to encounter:

Basal cell carcinoma. This is the most common type of skin cancer on the eyelid, accounting for 90% to 95% of all malignant eyelid tumors, and is the most common human malignancy overall.1,19,20 Though it rarely metastasizes, BCC can be locally invasive, even invading the orbit. In order of prevalence, BCC most often occurs on the lower lid, followed by the medial canthus, upper eyelid and lateral canthus.1,10,21 Variations in UV exposure of the different eyelid locations explains these prevalences.22 In parallel, the highest risk for orbital and sinus invasion involves lesions of the medial canthal area.1,10,21 Signs of orbital invasion include a firm mass that may cause displacement of the globe or restrictive strabismus.23 These signs warrant urgent diagnostic imaging. Incidence is approximately 500 to 1000 per 100,000, and men are affected more than women. Those with fair skin and a history of chronic sun exposure are likely victims.10

|  |  |

| Shown above is the reconstruction of an eyelid with basal cell carcimona. Click image to enlarge. | Pictured above is an example of a lentigo maligna. Click image to enlarge. Photo: VisualDx | A basal cell carcinoma is depicted here. Click image to enlarge. |

These lesions appear as firm, round-to-oval bumps on the skin surface (i.e., nodular form) that, as they grow, develop pearly, raised borders with telangiectasia and a central ulcerated core (i.e., noduloulcerative form). A third subset, sclerosing or morpheaform BCC, is less well defined and thus more difficult to diagnose, as it tends to spread beneath the skin surface.1,21 Prognosis is good when the lesion is completely excised, though any tumor remnants left behind tend to be agressive.1 Mohs surgery or frozen sections should be employed to ensure complete excision. Surgical reconstruction may be required depending on the size of the lesion. Radiation treatment may be employed only in cases of poor surgical candidates, while chemical agents such as imiquimod may only be used for lesions not located on the eyelid margin.10

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cogan Collection, NEI/NIH |

|

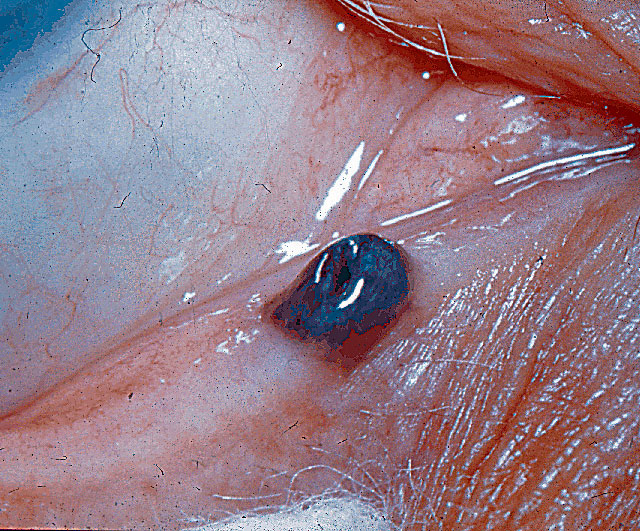

| Melanoma of punctum. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cogan Collection, NEI/NIH |

|

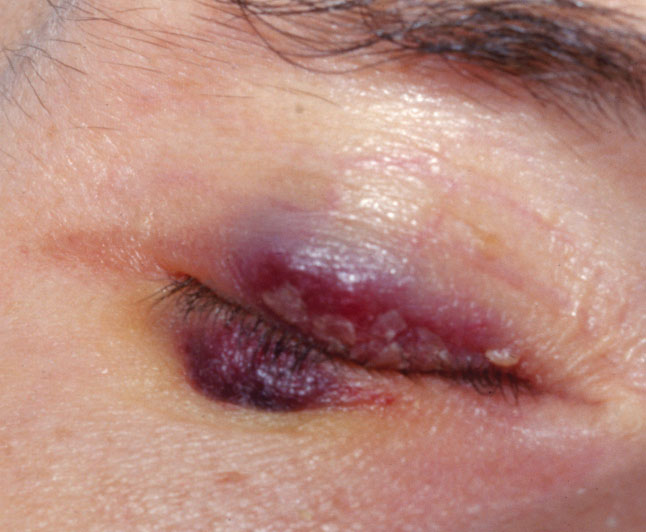

| Kaposi’s sarcoma. Click image to enlarge. Photo: VisualDx/NEI/NIH |

|

| Pictured here is the reconstruction of an eyelid after excision and Hughes flap. Click image to enlarge. |

Squamous cell carcinoma. This is far less common than BCC, with an incidence of 12 per 100,000 white males.10 It is about half as common in white females and about a tenth as common in blacks. UV light and exposure to ionizing radiation cause malignant transformation of epidermal squamous cells.10,11 SCC most often appears on the lower eyelid, especially the eyelid margin.1,10 In fact, while far less prevalent than BCC, SCC is more common on the upper eyelid and lateral canthus.11

These lesions can take on many forms. Like BCC, SCC appears in multiple presentations. These include a nodular presentation with a firm hyperkeratotic appearance, an ulcerating presentation with distinct, inflamed borders and central crater, and a buried, aggressive form with a superficial cutaneous horn.1,10 Though less common than BCC, SCC carries more risk as it is more aggressive and spreads to regional lymph nodes in 20% of cases.1 It has also been known to spread intracranially by growing along nerves, including the trigeminal, oculomotor and facial nerves.1,24,25 Fortunately, the majority of lesions are not aggressive and can be treated by surgical excision, preferably by frozen section or Mohs surgery. Some may be treated with topical imiquimod cream if they are not located on the eyelid margin.10

Sebaceous adenocarcinomas (SGC). Although rare, these are highly malignant and potentially lethal (5% to 10% mortality).1 Arising from the sebaceous glands of the eyelid, they are sometimes initially mistaken for chalazia.1 One of the few malignant eyelid tumors more common in females, this lesion usually arises from a dysplastic meibomian gland or gland of Zeiss in patients over the age of 50.1,11 SGC has a predilection for the upper eyelid, likely due to the higher number of meibomian glands relative to the rest of the eye.1,11 The Wills Oculoplastics Manual describes sebaceous adenocarcinoma as “the Great Masquerader.” Thus, any chronic blepharitis or recalcitrant chalazion in a middle aged or elderly woman should evoke suspicion.

Nodular SGC. This presents as a hard mass in the upper eyelid, often containing yellowish lipid material, which is highly characteristic.1

Spreading SGC. This is less obvious, infiltrating through the dermis and causing a diffuse thickening of the lid and loss of lashes.1 Suspicion should prompt referral for biopsy, which in and of itself poses some concern, as special staining and treatment of samples must be performed, or the diagnosis could be incorrect. The surgeon must alert the pathologist as to the suspected etiology. Wide excision with controlled margins is necessary because this aggressive tumor sometimes has skip areas and could recur or spread without appropriate treatment.9,11 Therefore, vigilant follow-up is warranted. If diagnosis of SGC is confirmed, the patient will need to be seen by their primary care doctor immediately to rule out metastases.9,11

Malignant melanoma. This is not common. In fact, it comprises only about 1% of eyelid malignancies. Despite the lower incidence, melanoma is the cause of over 60% of deaths from all cutaneous cancers.11 Whites, especially those with a history of severe sunburns, are at a higher risk. Many are identified after a patient notices a change in color or increased size of a longstanding mole.10 Four subtypes exist:

- Lentigo malignant melanoma, which arises from lentigo maligna, may exist for a number of years as a pigmented macule up to several centimeters in diameter with irregular borders.

- Superficial spreading melanoma is smaller and mildly elevated. As it begins to transform and invade deeper tissues, the lesion appearance changes, becoming multi-nodular and indurated.

- Acral lentiginous melanoma occurs mostly on nonocular tissues.

- Nodular melanoma is the most common form affecting the eyelids. It presents variably as a darkly pigmented to amelanotic nodule, which grows rapidly with notable bleeding and ulceration.11 These dangerous lesions often spread despite aggressive excision efforts with controlled surgical margins. Sentinel lymph node (nearest the lesion) biopsy is required due to the propensity to spread via lymphatics. These malignancies have a high rate of distant metastasis, which may occur years after the initial lesion. The eight-year survival rate is 33% (greater than 3.6mm) to 93% (less than 0.76mm) depending on the tumor depth.10 Careful follow-up care with their primary care doctor is needed long-term for these patients.

Kaposi's sarcoma of the eyelid. This is rare, but when present likely signifies an immunocompromised state. These vascular tumors appear as red-to-purple elevations on the skin surface. They can be removed by excision, cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutic agents. Large lesions may require radiation. The presence of these lesions in an HIV-positive patient signifies an advanced disease state (AIDS), hence short-term mortality is high.10

Merkel cell carcinomas. These are rare, highly aggressive tumors affecting older individuals. They arise from sensory touch receptors within the eyelid. Characteristic appearance is a slightly purplish, well-defined nodule most commonly in the upper eyelid with no ulceration. At the time of presentation, it is estimated that 50% have metastasized. Treatment is excision followed by chemotherapy or radiation.1

Eyelid neoplasms are a common entity encountered in optometric practice. While the vast majority of these neoplasms are benign, it is of the utmost importance to recognize any potential malignancy. The management of these malignancies requires prompt referral to oculoplastics for biopsy and reconstruction; early intervention minimizes the amount of collateral tissue damage, resulting in easier reconstruction. This allows for retention of normal eyelid function, preservation of the globe, a functional lacrimal system and a pleasing cosmetic outcome.2 Thankfully, a thorough case history and physical examination can easily help the primary care optometrist decide when referral is needed and avert adverse ocular and systemic outcomes related to malignant eyelid neoplasm. n

Dr. Bendure is a staff optometrist at the Ernest Childers VA Outpatient Clinic in Tulsa, OK, and an adjunct faculty member with Oklahoma College of Optometry.

Dr. Burress is a staff optometrist at Ernest Childers VA Outpatient Clinic in Tulsa, OK, and an adjunct faculty member with Oklahoma College of Optometry.

| 1. Bowling B, Kanski J. Kanski’s clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach. 8th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2016. Print. 2. Dekmezian M, Cohen P, Sami M, Tschen J. Malignancies of the eyelid: a review of primary and metastatic cancers. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:903-26. 3. Kumar V, Robbins S, Cotran R. Basic Pathology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997. Print. 4. Lubell J. In scope. AOA Focus. Nov/Dec 2014:22-9. 5. Eisenberg J. Kentucky expands O.D.s’ scope of practice. Rev Optom. 2011;148(3):4-6. 6. Louisiana Gov Jindal signs expanded scope of practice bill. AOA News. June 2, 2014. www.aoa.org/news/advocacy/louisiana-governor-jindal-signs-expanded-scope-of-practice-bill?sso=y. Accessed March 27, 2017. 7. Legislation in Tennessee to allow ODs to use injectable anesthetic. Rev Optom. 2014;151(4):8. 8. Deprez M, Uffer S. Clinicopathological features of eyelid skin tumors. A retrospective study of 5504 cases and review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31(3):256-2. 9. Pe’er J. Pathology of eyelid tumors. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(3):177-90. 10. Penne R. Oculoplastics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; 2012. Print. 11. Yanoff M, Duker J. Ophthalmology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014. Print. 12. Proia A, Gayre G, Dutton J. Diagnostic atlas of common eyelid diseases. New York:Informa Healthcare; 2007. Print. 13. Casser L, Fingeret M, Woodcome H, et al. Atlas of primary eyecare procedures. 2nd ed, Norwalk:Appleton & Lange; 1997. Print. 14. Smoller B, Van de Rijn M, Lebrun D, et al. bcl-2 expression reliably distinguishes trichoepitheliomas from basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:28-31. 15. Heidarpour M, Rajabi P, Sajadi F, et al. CD10 expression helps to differentiate basal cell carcinoma from trichoepithelioma. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(7):938-44. 16. Hernandez A, Torrelo A. Recent data on the risk of malignancy in congenital melanocytic nevi: the continuing debate on treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:185-9. 17. Schwartz R. Congenital nevi treatment and management. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1118659-treatment. Medscape. June 10, 2016. Accessed February 17, 2017. 18. Bauer J, Garbe C. Risk estimation for malignant transformation of melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(1):127. 19. Moul D, Zabielinski M, Choudhary S, Nouri K. Mohs micrographic surgery for eyelid and periorbital skin cancer. Int Ophthalmol. Clin. 2009:49(4):111-27. 20. Madge S, Khine AA, Thaller VT, et al. et al. Globe sparing surgery for medial canthal basal cell carcinoma with anterior orbital invasion. Ophthalmol. 2010;111(11):2222-8. 21. Gündüz K, Esmaeli B. Diagnosis and management of malignant tumors of the eyelid, conjunctiva, and orbit. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2008;3(1):63-75. 22. How Sunlight Damages Your Eyes. www.skincancer.org/prevention/sun-protection/for-your-eyes/how-sunlight-damages-the-eyes. Skin Cancer Foundation. December 7, 2012. Accessed February 27, 2017. 23. Slutsky J, Jones E. Periocular cutaneous malignancies: A review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:552-69. 24. Kasenchak J, Notz G. Eyelid lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Rev Ophthalmol. 2016;23(4):71-5. 25. Bernardini F. Management of malignant and benign eyelid lesions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:480-4. 25. Muller F, Dawe R, Moseley H, Fleming C. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue-sparing outcome. Dermatol Sur. 2009;35:1349-54. 27. Tildsley J, Diaper C, Herd R. Mohs surgery vs primary excision for eyelid BCCs. Orbit. 2010;29(3):140-5. 28. Ong L, Lane C. Eyelid contracture may indicate recurrent basal cell carcinoma, even after Mohs micrographic surgery. Orbit. 2009;28:29-33. 29. Rowe D, Carroll R, Day Jr C. Long term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315-8. 30. Rowe D, Carroll R, Day Jr C. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:424-31. |