|

How to Assess and Manage Nystagmus and Vertigo

When a patient’s “world spins ‘round,” optometrists need to be able to identify the cause and take action.

By Saidivya Komma, OD, Kristine Loo, OD, Rachel Werner, OD, and Heather Whyte, OD

Release Date: August 15, 2022

Expiration Date: August 15, 2025

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: 2 hours

Jointly provided by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and Review Education Group

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

Recognize the potential causes of vertigo and nystagmus.

Identify and assess these conditions among their patients.

Explain the vestibular system and its relationship to ocular function.

Determine when these conditions indicate a medical emergency.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in managing patients with nystagmus and vertigo.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by PIM and the Review Education Group. PIM is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education and the American Nurses Credentialing Center to provide CE for the healthcare team. PIM is accredited by COPE to provide CE to optometrists.

Reviewed by: Salus University, Elkins Park, PA

Faculty/Editorial Board: Saidivya Komma, OD, Kristine Loo, OD,Rachel Werner, OD,and Heather Whyte, OD

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Activity #124410 and course ID . Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements: PIM requires faculty, planners and others in control of educational content to disclose all their financial relationships with ineligible companies. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted and mitigated according to PIM policy. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality, accredited CE activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in healthcare and not a specific proprietary business interest of an ineligible company.

Those involved reported the following relevant financial relationships with ineligible entities related to the educational content of this CE activity: Authors: Drs. Komma, Loo, Werner and Whyte have no relevant financial interests to disclose. Managers and Editorial Staff: The PIM planners and managers have nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group planners, managers and editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

|

Demonstration of the use of +20.00D lenses in a trial frame. Click image to enlarge. |

A case involving visual complaints of spinning, tilting or jumping vision can be intimidating and overwhelming, but understanding the basics of nystagmus and vertigo can aid in managing these patients and referring urgently to the correct specialist when indicated.

The basic definition of nystagmus is the rapid and uncontrolled movement of both eyes, typically in a fast or slow rhythmic pattern, whereas vertigo is defined as the sensation of self-motion in a still environment.1,2 Patients may present to your office with symptoms of decreased visual acuity, vertigo, dizziness or difficulty with balance, a tilted or turned head position, sensitivity to light or even oscillopsia, which is defined as the jumping or moving of the visual environment.1

This article will explore how these conditions often present in optometric practice and discuss the role of the optometrist. It will help you better understand nystagmus and vertigo and feel more comfortable assessing and managing these patients.

What to Know About Nystagmus

Nystagmus can either be acquired or congenital. The latter is not usually associated with any other abnormalities but can be due to developmental abnormalities within the eye; however, symptoms from congenital nystagmus are typically transient and will resolve on their own in a few months to a few years without any visual disruption.3 Alternatively, acquired nystagmus typically involves a medical and/or neurologic cause with damage to the peripheral or central vestibular or visual pathways that requires an urgent investigation.1,4

Nystagmus can be further distinguished by two characteristics: jerk or pendular, with jerk being the more common of the two.

Pendular. This type of nystagmus has phases of equal velocity.4 It does not have a fast phase and can occur in any direction including torsional, vertical, horizontal or mixed.4 This can result in circular, oblique or elliptical trajectories.5

Pendular nystagmus from childhood can be from spasmus nutans, a pediatric disorder that involves a triad of nystagmus, head bobbing and torticollis, or it can develop from visual deprivation.4,5 Acquired pendular nystagmus is most often caused by multiple sclerosis, brainstem infarction or cerebellar disease.4

See-saw nystagmus is a subtype of pendular nystagmus where one eye rises and intorts while the other eye descends and extorts; it is more commonly caused by a parasellar mass such as a craniopharygioma or pituitary adenoma.5,6 Head trauma or visual disorders such as cone-rod dystrophies and retinitis pigmentosa can also cause see-saw nystagmus.5

Jerk. This nystagmus type has a slow phase that is followed by a fast phase.6 It is usually described in the direction of the fast phase; however, it is the slow phase that results from the pathological or abnormal cause.6 Acquired jerk nystagmus in the primary position can be classified into different types based on their trajectory, including downbeat, upbeat, horizontal, torsional and mixed.7

Downbeat nystagmus is the most common type of acquired nystagmus, with a pathologic upward slow phase and a downward fast phase.4 Downbeat nystagmus can present with abnormal downward pursuits and an alternating hypertropia in lateral gaze that can exhibit as an alternating skew deviation.4,8 This type of nystagmus also obeys Alexander’s law, as the nystagmus increases in intensity when looking at the direction of the fast phase; in this case, the nystagmus would be more enhanced in downgaze.8

Approximately 30% of downbeat nystagmus patients are idiopathic followed by approximately 24% from cerebellar degenerations with lesions at the cervicomedullary junction and foramen magnum and 13% from cerebellar ectopias mainly from Chiari malformations.8 Less common causes are from infarctions, vascular lesions, multiple sclerosis, toxicity, tumors, trauma and infectious, paraneoplastic or metabolic etiology.8

Upbeat nystagmus has a slow downward phase and a fast upward phase. Large-amplitude upbeat nystagmus lesions have been suggested to be located in the anterior cerebellar vermis and small-amplitude upbeat nystagmus, in the medulla.8 Similar to downbeat nystagmus, less common causes have been reported to be from infarctions, multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating diseases, Chiari malformations and cerebellar degenerations.8

Horizontal nystagmus can occur from peripheral or central vestibular lesions.8 Peripheral lesions from vestibular neuritis or partial neurectomy are causes of pure horizontal nystagmus where the fast phase is typically directed away from the side of the lesion.1 Horizontal nystagmus from peripheral lesions can be suppressed with visual fixation making it difficult to assess and diagnose.1 With central vestibular lesions, however, horizontal nystagmus persists, or can even worsen, with fixation and often presents as periodic alternating nystagmus where the horizontal nystagmus beats in one direction for a couple of minutes then beats in the other direction.9 It is important to note that Alexander’s law is followed in nystagmus due to peripheral vestibular lesions which can help differentiate from central vestibular lesions.10

Periodic alternating nystagmus can be congenital or acquired from damage to the vestibulocerebellar pathways, cerebellar degeneration, multiple sclerosis, stroke, tumors or infections.8 Pure torsional nystagmus typically has a central cause with lesions located at the medulla, pons, cerebellum or mesencephalon resulting in an imbalance of the vertical semicircular canal function.11 Pure torsional nystagmus is most commonly caused by brainstem infarction or multiple sclerosis, can beat either toward or away from the side of the lesion and can present with oscillopsia and a skew deviation.6,12

|

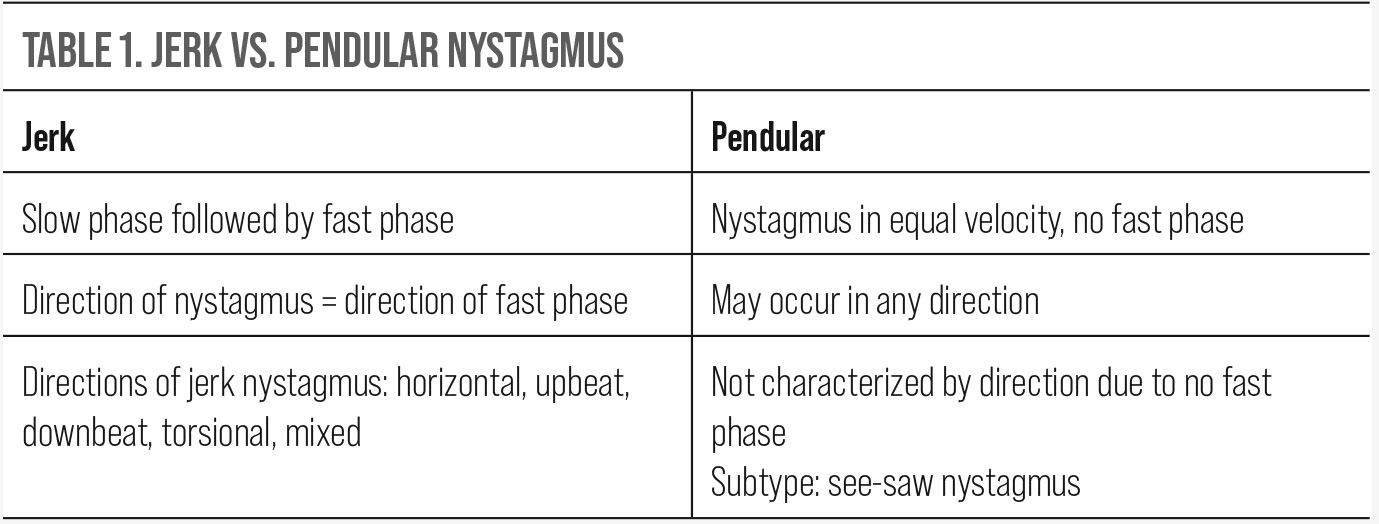

| Click table to enlarge. |

Nystagmus can be a physiologic response to the environment as optokinetic nystagmus or a vestibulo-ocular reflex from head rotations, congenital factors or pathologic reasons due to damage to the vestibular or visual pathways.13 The most common symptom of nystagmus is vertigo or spinning sensations due to a disruption in the vestibular pathway.7,9,13

A broad overview of the vestibular system is categorized into the peripheral and central pathways. The peripheral system involves the semicircular canals, the otolithic organs and the vestibular portion of cranial nerve VIII.9,13 There are three semicircular canals that detect head rotation.9 The otolith organs include the utricle and saccule, which detect linear acceleration and head position.9 These peripheral system organs play a role in the vestibulo-ocular reflex, providing compensatory eye movements to allow images to remain steady on the fovea during head movements.4

The central vestibular system involves input from the vestibular organs along with the somatosensory and visual systems to the vestibular nuclei and cerebellum to maintain a sense of balance and position.9,13 Symptoms of vertigo from nystagmus are mostly associated with peripheral vestibular disease but can include involvement from the central vestibular system as well.7 When associated with the central vestibular system, this could result in the need for urgent care.

When a patient presents with acute vertigo combined with a clinical sign of nystagmus, one of the first areas to assess is whether this is a central or a peripheral vestibular system condition. Differentiating between a central or peripheral vestibular condition will help dictate the urgency of the patient’s complaints. Vertigo that localizes to the central vestibular system could indicate neurologic ischemia or infarction.14

Central vertigo will usually present with more mild symptoms that are constant and do not wax and wane with time, whereas peripheral vertigo usually presents with sudden and severe onset of symptoms that can be episodic or even change with posture positioning.14,16 Also, peripheral vertigo can be linked with a viral illness, such as herpes zoster, and the presence of a rash may be seen.9

Other associated findings for peripheral vertigo are related to other vestibulocochlear symptoms such as tinnitus or loss of hearing, but central vertigo, due to its correlation with brainstem involvement, will present with neurologic symptoms (i.e., weakness, numbness or diplopia).14

Once the likely underlying etiology is determined, creating a list of differential diagnoses can aid in further assessment and management of the patient. The most common cause for central vertigo, especially in elderly patients, is ischemia of the central vestibular structures—the cerebellum, brainstem and vestibular nuclei. However, in younger patients, the most common cause is due to acute demyelination, such as multiple sclerosis.

Some less common causes of central vertigo include medication (i.e., anticonvulsants such as phenytoin, phenobarbital and carbamazepine), infection, trauma, a posterior fossa brain tumor, rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency, Wallenberg’s syndrome syndrome, Chiari malformation, multiple sclerosis, episodic ataxia type 2, disembarkment syndrome and migraine.14,15

Peripheral vertigo is typically caused by benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Other, less common causes are acute labyrinthitis, acute vestibular neuritis, cholesteatoma, herpes zoster oticus, Meniere’s disease, otosclerosis, perilymphatic fistula, vestibular neuritis, labyrinthine concussion, semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome, vestibular paroxysmia, Cogan’s syndrome, recurrent vestibulopathy, vestibular schwannoma, aminoglycoside toxicity and otitis media.14-16

Vestibular neuritis occurs from inflammation of the eighth cranial nerve, most commonly sequelae from a viral infection.14 Meniere’s disease is thought to be caused by increased endolymphatic fluid pressure causing inner ear dysfunction.14

|

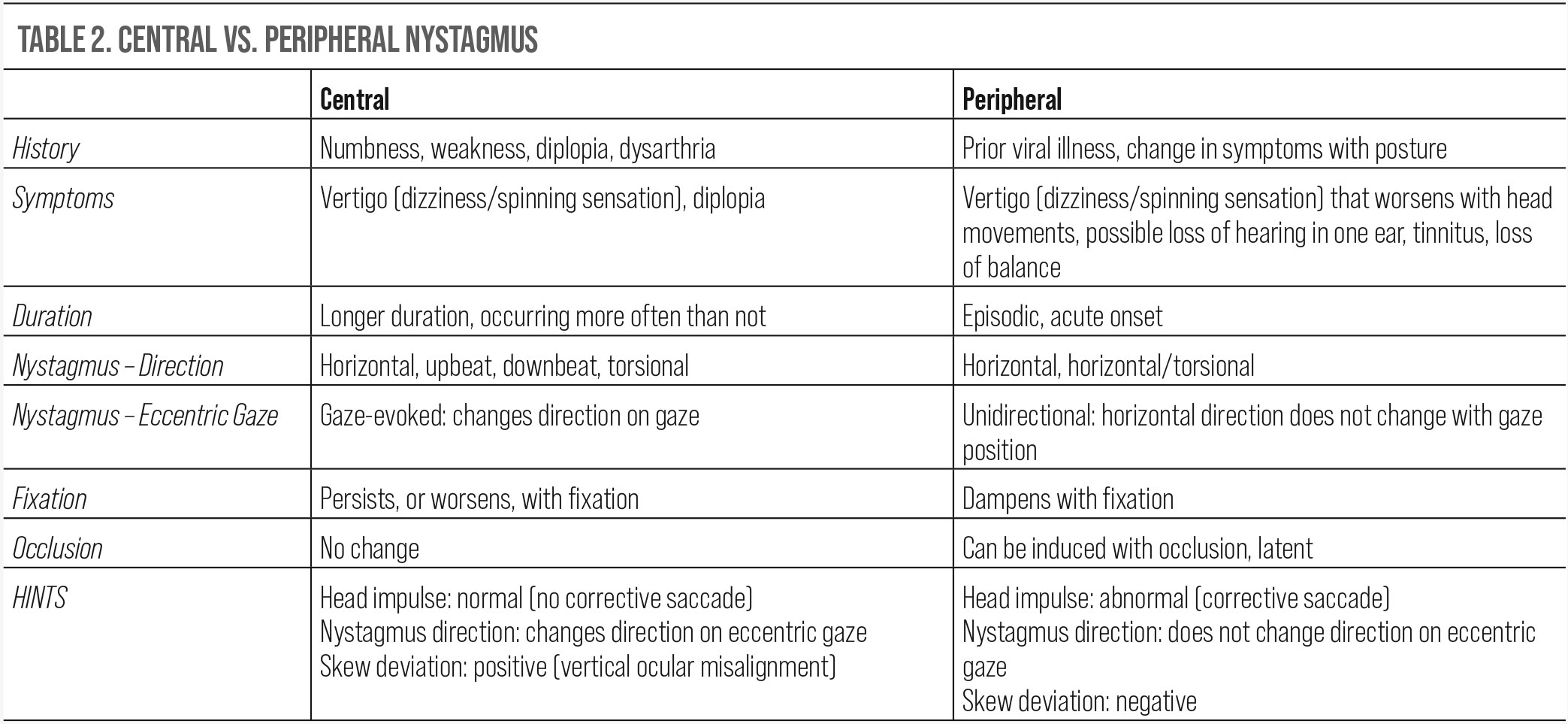

| Click table to enlarge. |

Central vs. Peripheral Vertigo

The first step in determining the underlying cause is the initial intake, or history. Particularly in cases of transient vertigo where symptoms cannot be elicited in-office, patient history may be the only information available to help with diagnosis. Taking a detailed history will aid in differentiating between central vs. peripheral vertigo.

Several important questions to ask are the onset of symptoms, frequency of symptoms, any recent illnesses or presence of a rash, change in symptoms related to posture, associated headaches, tinnitus or even loss of hearing or any other associated symptoms that could be indicative of brainstem involvement such as weakness, numbness or double vision.2,14,16

When taking a history for these patients, a useful acronym to go by is TiTrATE: timing, triggers and targeted examination.17,18 By gathering this data, the type of vertigo can be categorized into episodic triggered, spontaneous episodic or continuous vestibular.17 This may be useful in narrowing down differential diagnoses.

Another important component of history intake is to document current medication use, as any drugs that pose a risk for hypotension, hypoglycemia, anticholinergic side effects of the central nervous system, cerebellar toxicity and ototoxicity can induce vertigo.18 Next, the patient’s blood pressure should be measured while standing and supine to assess for the most common cause of episodic triggered vertigo, which is orthostatic hypotension.17-19 Orthostatic hypotension, which accounts for positional changes in blood pressure, is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure by 20mm Hg, a drop in diastolic blood pressure by 10mm Hg or a pulse increase by 30 beats per minute.18

Clinical Examination

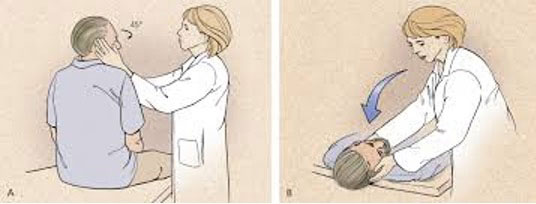

Following the initial intake, a physical exam will further aid in differentiating between a central or a peripheral vestibular system etiology. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver may be performed in-office to diagnose the most common cause of vertigo in adults: BPPV.18,20,21 This is a non-ischemic disorder of the inner ear due to misplaced calcium crystals and debris usually located in the posterior semicircular canal.20

To perform the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, the patient must first be sitting upright while the doctor positions the patient’s face 45° to the right. The doctor then quickly but gently lays the patient on their back while supporting their head, which should partially hang off the exam table. This position should be maintained for 30 to 60 seconds, during which the patient’s eye movements must be assessed for nystagmus. If no nystagmus is present after 60 seconds, the patient should sit upright again for another 30 seconds. This procedure should then be repeated with the patient’s face turned to the left in order to test the other ear. The symptoms associated with a positive result will be triggered when the affected ear is facing down. If the maneuver induces vertigo, either with or without nystagmus, this is a positive test and confirms the diagnosis of BPPV. However, a negative test does not definitively rule out BPPV.18

If the Dix-Hallpike test is negative, the next step is to rule out a stroke by performing a series of tests known as HINTS.2,15,22 The HINTS examination stands for head impulse testing, direction of nystagmus and test of ocular skew deviation. Using the HINTS evaluation tool as part of the clinical assessment can be helpful to determine if the etiology lies within the peripheral or central nervous system. It is important to note that not all patients are good candidates for HINTS testing, and it should be avoided in the following cases: head trauma, neck trauma, spinal instability, concern for arterial dissection and severe carotid stenosis.22 The components of the HINTS exam are as follows:

Head impulse testing. While the patient is sitting upright and fixating on the examiner’s nose or a nearby object, the examiner will rapidly move the patient’s head from side to side by 10°. In the setting of a central vertigo, there will be no corrective saccade back to fixation; however, in the setting of a peripheral vertigo, there will be.22

Direction of nystagmus. While testing extraocular motility, assess for the presence of nystagmus that may or may not change direction on eccentric gaze. The examiner will assess the patient viewing in primary gaze and then lateral gaze. If the nystagmus direction changes, this would be consistent with a gaze-evoked nystagmus and likely a central vertigo, whereas in peripheral vertigo the nystagmus will not change direction. If the test elicits a horizontal nystagmus that exacerbates when gazing in the direction of the nystagmus, there is likely a peripheral cause. If there is a vertical or torsional nystagmus, there is likely a central cause. Nystagmus secondary to peripheral causes can be suppressed with fixation.

Test of ocular skew deviation. The test of a skew deviation, or a vertical ocular misalignment, will also aid in determining a central vs. peripheral cause of vertigo. While the patient is centrally fixated at a distant target, perform an alternating cover test. If the covered eye exhibits a vertical deviation or positive skew deviation after uncovering it, there is likely brainstem involvement related to central vertigo.23

These tests may be performed remotely as well, through synchronous or asynchronous telemedecine.21 In fact, video-oculography technology has been shown to improve accuracy in identifying a positive head impulse test or presence of nystagmus.19,21 One important condition that does not follow this formulaic workup is anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) ischemia, which will have cerebellar and brainstem involvement and a positive head impulse test despite its central etiology.2,17-19 In this case, use HINTS+, where the + accounts for unilateral hearing loss that is typical of AICA ischemia to the lateral pons.2,17-19

Central HINTS findings include a normal head impulse test (no corrective saccade), nystagmus that changes direction on eccentric gaze and a positive skew deviation test. Peripheral findings include an abnormal head impulse test (corrective saccade), nystagmus that does not change direction on eccentric gaze and a negative skew deviation test.

A multidirectional or gaze-evoked nystagmus is typically associated with central vertigo, whereas a unidirectional horizontal nystagmus is observed with peripheral vertigo.2,14,16

One study found a correlation between retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and central vertigo as measured via OCT. Considering that the central retinal artery is an indirect branch of the internal carotid artery, it is likely the ischemic etiology of central vertigo that leads to mild thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer.24 In isolated cases of vertigo, in the absence of nystagmus and presence of other neurologic abnormalities, neuroimaging is indicated. Since vertigo is most commonly associated with posterior circulation insufficiency, a vertebrobasilar Doppler is recommended for further evaluation if the diffusion-weighted MRI is unremarkable for stroke.19

|

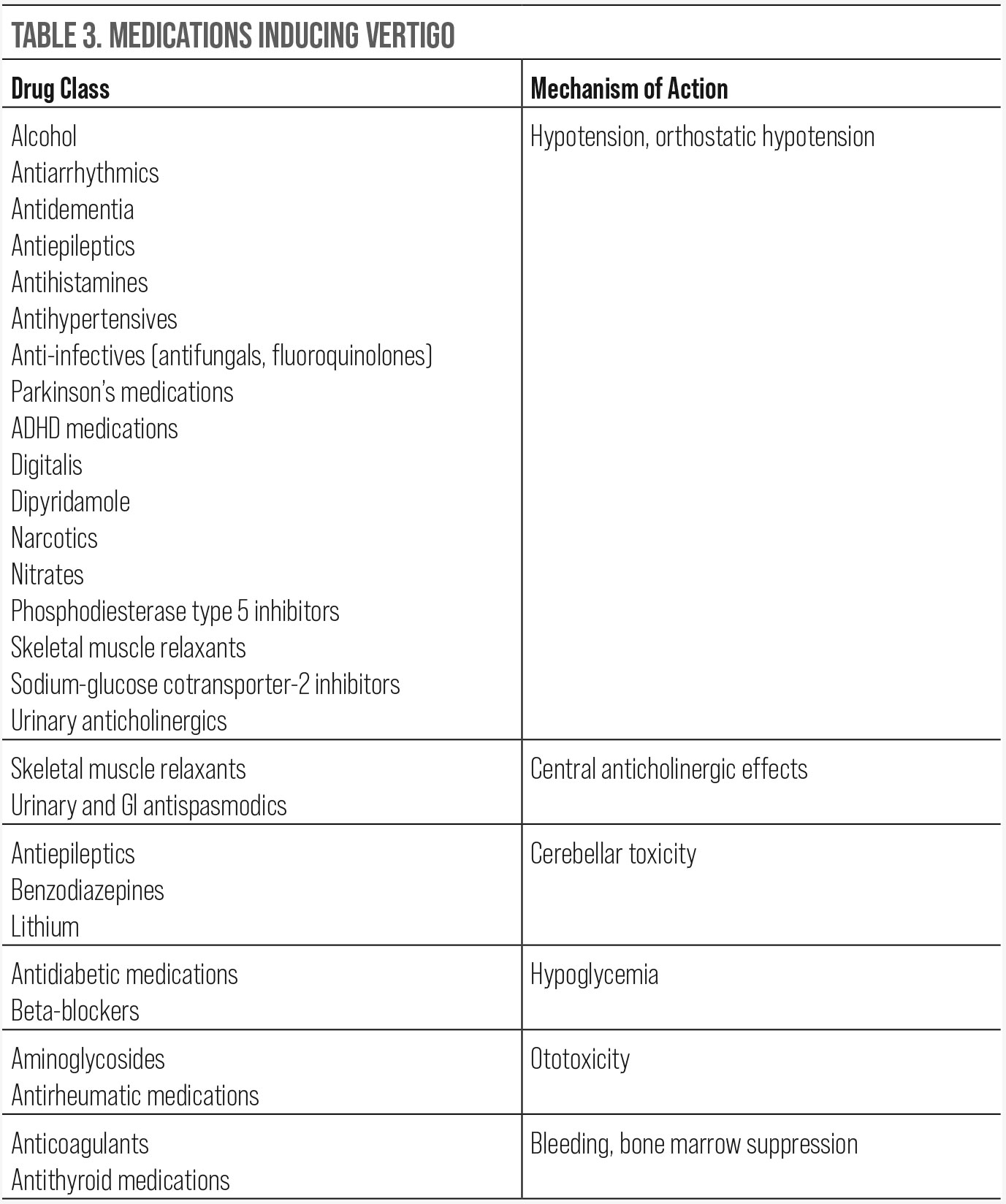

| Click table to enlarge. |

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Patients who have suffered a TBI may have complaints of vertigo, a major cause of disability following brain injury as some patients are unable to work through their symptoms.

Post-traumatic vertigo can occur from a traumatic vestibulopathy, although some patients who have no evidence of a vestibulopathy experience vertigo-like symptoms. In these cases, there is no clear understanding as to why their symptoms occur, but it is thought that the injury can result in microscopic damage to both the central and peripheral vestibular systems. One study showed that vestibular rehabilitation therapy may or may not be helpful, with patients reporting an improvement in symptoms but many still unable to return to work.25

The Role of the OD

Vertigo secondary to ischemic causes is rare, as only 3% to 5% of cases are secondary to a stroke, but proper diagnosis can prevent severe functional loss if vascular insufficiency is confirmed early.17 That percentage may be grossly underestimated due to the frequency of misdiagnosis in these cases.

The underlying cause must be found to address treatment. Neuroimaging with a focus on the midbrain and posterior fossa is indicated in vascular episodes. Keep in mind that CT and MRI have poor sensitivity in detecting ischemic events affecting the vestibular system and posterior circulation.2,17,19 Peripheral lesions of the vestibular system that lead to vertigo are often benign; however, central lesions are likely secondary to stroke.19 An appropriate workup assessing visual, ocular motor and vestibular function in-office is more sensitive than neuroimaging in detecting an acute stroke related to vertigo.17

Other signs and symptoms of stroke include diplopia, dysarthria, ataxia, dysphasia and dizziness. Be aware that patients with a lateral medullary infarction (Wallenberg’s syndrome) almost always present with a horizontal or torsional nystagmus.26 If the nystagmus is horizontal, the fast phase will be beating away from the side of insult.27 These patients may also present with Horner’s syndrome, unilateral ataxia and difficulty sitting or walking.26

Wallenberg’s syndrome is commonly caused by vertebral artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery occlusion.26 When this syndrome is suspected, perform MRA with head imaging to aid in diagnosis. If results come back unremarkable, consider looking into drug toxicity as the source of the nystagmus. Possible causes of drug-induced nystagmus include anticonvulsants, organophosphate poisoning and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.28-30

Proper evaluation of nystagmus can help aid in localization of the issue. Observe the patient in primary gaze and determine the type of nystagmus (jerk vs. pendular) and the direction of the nystagmus. Evaluate the nystagmus both with and without fixation. Trial +20.00D lenses to assess nystagmus without fixation. If the nystagmus is suppressed, this would indicate a peripheral lesion.

It is important to observe the nystagmus in all directions of gaze to identify a null position. The null position will give the patient the best visual acuity and fewest symptoms. If prescribing yoked prism to put the patient in the null position, the apex should be pointing toward the null point. A small amount of base-out prism can be prescribed if the nystagmus is dampened with convergence. Educate the patient that this should reduce their symptoms in primary gaze, but as they move their eyes, symptoms may increase.

Neurology referral for the medical treatment of nystagmus may be necessary. Medications are dependent on the type of nystagmus present, but the most common ones include clonazepam, aminopyridines, baclofen and memantine.16 Although these medications may help with reducing nystagmus, your patient may still feel symptomatic as dizziness and incoordination are possible side effects from these drugs.16 Other options for the treatment of nystagmus include a combination of high-plus glasses over high-minus contact lenses or auditory/tactile feedback devices.31

|

| Patient positioning in treatment of vertigo.32 Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

Patients who experience nystagmus or vertigo may present to a primary eyecare clinic for further assistance. Determining the underlying condition is imperative in providing additional care or appropriate referrals.

Dr. Komma serves as an externship coordinator and staff optometrist at the Kernersville VA Health Care Center. She graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry (PCO) and completed her ocular disease residency at the Salisbury VA Medical Center. Dr. Loo is a staff optometrist and eye clinic section chief at the Kernersville VA Health Care Center. She graduated from the Illinois College of Optometry and completed her residency in primary care/ocular disease at the Salisbury VA Medical Center. Dr. Werner is a staff optometrist at the Kernersville VA Health Care Center. Dr. Whyte recently transferred from the Salisbury VA Health Care System to the Durham VA Health Care System. She graduated from and completed her low vision rehabilitation residency at PCO. They have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Kates MM, Beal CJ. Nystagmus. JAMA. 2021;325(8):798. 2. Shemesh AA, Gold DR. Dizziness and vertigo: the skillful examination. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020;40(3):e49-e61. 3. Young TL, Weis JR, Summers CG, et al. The association of strabismus, amblyopia, and refractive errors in spasmus nutans. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(1):112-7. 4. Liu, GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta S. (2018). Chapter 17–Eye Movement Disorders: Nystagmus and Nystagmoid Eye Movements. In Neuro-Ophthalmology: Diagnosis and Management. essay, Elsevier. 5. Barton JJS. Pendular nystagmus. UpToDate (January 13, 2022). Retrieved from: www.uptodate.com. 6. Payne A, B.M (2007) The Neuro Ophthalmology Survival Guide. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. 7. Barton JJS. Overview of nystagmus. UpToDate (May 29, 2019). Retrieved from: www.uptodate.com. 8. Tran TM, Lee MS, McClelland CM. Downbeat nystagmus: a clinical review of diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32(6):504-14. 9. Thompson TL, Amedee R. Vertigo: a review of common peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Ochsner J. 2009;9(1):20-6. 10. Jacobson GP, McCaslin DL, Kaylie DM. Alexander’s law revisited. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008;19(8):630-8. 11. Lopez L, Bronstein AM, Gresty MA, et al. Torsional nystagmus. A neuro-otological and MRI study of thirty-five cases. Brain. 1992;115( Pt 4):1107-24. 12. Barton JJS. Jerk nystagmus. UptoDate (November 8, 2021). Retrieved from: www.uptodate.com. 13. Farrell L. Peripheral versus central vestibular disorders. 2019. Vestibular Rehabilitation Special Interest Group. www.neuropt.org/docs/default-source/vsig-physician-fact-sheets/peripheral-versus-central-vestibular-disorders.pdf?sfvrsn=58da5343_0. 14. Lui F, Foris LA, Willner K, et al. Central Vertigo. [Updated 2022 May 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441861. 15. Labuguen, R. Initial evaluation of vertigo. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(2):244-51. 16. Baumgartner B, Taylor RS. Peripheral vertigo. [Updated 2021 Jul 2]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430797. 17. Saber Tehrani AS, Kattah JC, Kerber KA, et al. Diagnosing stroke in acute dizziness and vertigo. Stroke. 2018;49(3):788-95. 18. Muncie HL, Sirmans SM, James E. Dizziness: approach to evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(3):154-62. 19. Kim HA, Lee H, Kim, JS. Vertigo due to vascular mechanisms. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(01), 067–075. 20. Nuti D, Zee DS, Mandalà M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: What we do and do not know. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(01):049-058. 21. Green KE, Pogson JM, Otero-Millan J, et al. Opinion and special articles: remote evaluation of acute vertigo: strategies and technological considerations. Neurology. 2021;96(1):34-8. 22. Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The HINTS exam to differentiate central from Peripheral Vertigo. Department of Emergency Medicine. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://emergencymedicine.wustl.edu/items/the-hints-exam-to-differentiate-central-from-peripheral-vertigo. 23. Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, et al. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3504-10. 24. Kocak MN, Ates O, Ondas O, et al. Differential diagnosis of ischemic vertigo by optical coherence tomography. Eurasian J Med. 2020;52:288-91. 25. Marzo SJ, Leonetti JP, Raffin MJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of post-traumatic vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(10):1720-3. 26. Ogawa K, Suzuki Y, Oishi M, et al. Clinical study of 46 patients with lateral medullary infarction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(5):1065-74. 27. Brazis PW. Ocular motor abnormalities in Wallenberg’s lateral medullary syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67(4):365-8. 28. Wu D, Thijs RD. Anticonvulsant-induced downbeat nystagmus in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2015;4:74-5. 29. Nakamagoe K, Fujizuka N, Koganezawa T, et al. Residual central nervous system damage due to organoarsenic poisoning. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2013;37:33-8. 30. Kang S, Shaikh AG. Acquired pendular nystagmus. J Neurol Sci. 2017;375:8-17. 31. Thurtell MJ. Treatment of nystagmus. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(5):522-6. 32. Swartz R, Longwell P. Treatment of vertigo. Am Fam Physician 2005;71(6):1117. |