Improved Approaches to MIGS for Better Patient Outcomes

RELEASE DATE: March 5, 2018

EXPIRATION DATE: March 5, 2021

FACULTY

Murray Fingeret, OD

Clinical Professor

State University of New York College of Optometry

New York, New York

Joseph F. Panarelli, MD

Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Associate Residency Program Director

New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai

New York, New York

LEARNING METHOD AND MEDIUM

This educational activity consists of a supplement and ten (10) study questions. The participant should, in order, read the learning objectives contained at the beginning of this supplement, read the supplement, answer all questions in the post test, and complete the Activity Evaluation/Credit Request form. To receive credit for this activity, please follow the instructions provided on the post test and Activity Evaluation/Credit Request form. This educational activity should take a maximum of 1.0 hour to complete.

CONTENT SOURCE

This continuing education activity captures content from an expert roundtable discussion held on December 11, 2017.

ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION

Glaucoma specialists, ophthalmologists, and optometrists all play a role in the management of glaucoma. Recently, the spectrum of glaucoma surgical procedures has expanded to include minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS). Optometrists must become familiar with MIGS procedures, their indications, and associated complications. This continuing education activity reviews the current state of glaucoma surgery, including current and emerging MIGS devices and their efficacy and safety profiles.

TARGET AUDIENCE

This educational activity is intended for optometrists caring for patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be better able to:

- Articulate the features and safety and efficacy data of current and emerging MIGS devices

- Describe patient characteristics for referral for a potential surgical procedure on the basis of clinical evidence

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

COPE approved for 1.0 CE credit for optometrists.

|

COPE COURSE ID: 56980-GL

COPE COURSE CATEGORY: Glaucoma

ADMINISTRATOR:

DISCLOSURES

Murray Fingeret, OD, had a financial agreement or affiliation during the past year with the following commercial interests in the form of Consultant: Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Alcon; Allergan; Bausch & Lomb Incorporated; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc; Heidelberg Engineering GmbH; and Topcon Corporation.

Joseph F. Panarelli, MD, had a financial agreement or affiliation during the past year with the following commercial interests in the form of Advisory Board: Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc; and Allergan; Speaking and Teaching: Glaukos Corporation.

EDITORIAL SUPPORT DISCLOSURES

The staff of MedEdicus have no relevant commercial relationships to disclose.

DISCLOSURE ATTESTATION

The contributing physicians listed above have attested to the following:

- that the relationships/affiliations noted will not bias or otherwise influence their involvement in this activity;

- that practice recommendations given relevant to the companies with whom they have relationships/ affiliations will be supported by the best available evidence or, absent evidence, will be consistent with generally accepted medical practice; and

- that all reasonable clinical alternatives will be discussed when making practice recommendations.

PRODUCT USAGE IN ACCORDANCE WITH LABELING

Please refer to the official prescribing information for each drug discussed in this activity for approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

GRANTOR STATEMENT

This continuing education activity is supported through an unrestricted educational grant from Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd.

SPONSORED BY

TO OBTAIN CE CREDIT

We offer instant certificate processing and support Green CE. Please take this post test and evaluation online by clicking the Take Exam button at the end of this activity. Upon passing, you will receive your certificate immediately. You must answer 7 out of 10 questions correctly in order to pass, and may take the test up to 2 times. Upon registering and successfully completing the post test, your certificate will be made available online and you can print it or file it. Please make sure you take the online post test and evaluation on a device that has printing capabilities. There are no fees for participating in and receiving CE credit for this activity.

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in this educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the State University of New York College of Optometry; MedEdicus LLC; Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd; or Review of Optometry.

This CE activity is copyrighted to MedEdicus LLC ©2018. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The management of patients with glaucoma in the United States is shared by glaucoma specialists, ophthalmologists, and optometrists. The traditional glaucoma surgeries, trabeculectomy and tube-shunt implantation, are in most every glaucoma specialist's repertoire, and optometric referrals for glaucoma surgery are straightforward. In recent years, the spectrum of surgical procedures for glaucoma has broadened to include an array of minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGSs), with the goal of providing safer procedures for intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction. Today's optometrist must be familiar with these new procedures, their indications, and associated complications. It is important that optometrists know which surgeons in their community offer the various procedures to ensure efficient referrals for patients who may benefit from these interventions. In this educational activity, the current state of glaucoma surgery will be reviewed, with the goal of familiarizing readers with the features of current and emerging MIGS devices as well as their efficacy and safety profiles to facilitate the decision making that occurs during referral for glaucoma surgery.

Where Do MIGS Procedures Fit in Glaucoma Management?

Dr Fingeret On a daily basis, we are focused on controlling IOP and stabilizing the optic nerve and visual field. We should always keep in mind, however, that we attend to these aspects of glaucoma management for the purpose of preserving the patient's vision and overall quality of life.1,2

MIGS (Table 1)3–10 initially arose as an effort to develop a surgical procedure with the efficacy of a trabeculectomy or tube-shunt procedure, but with a more favorable safety profile. As we all know, trabeculectomy is highly effective for lowering IOP,11 but its safety profile includes potentially vision-threatening complications, such as hypotony maculopathy, blebitis, and endophthalmitis.12 MIGS procedures meet the IOP-lowering objective to varying degrees, and offer a surgical option beyond the traditional procedures for patients whose glaucoma cannot be controlled with medications and laser therapy. MIGS procedures also offer a surgical option for novel indications in glaucoma because of its excellent safety profile. One such novel indication is therapeutic nonadherence; multiple studies have indicated that many patients do not take their medications as prescribed,13 compromising IOP control and increasing their risk of vision loss. For a patient with early-stage glaucoma and a modest target IOP reduction who is nonadherent with medical therapy, MIGS may be a good alternative. Another evolving indication for glaucoma surgery is the presence of ocular surface disease (OSD). As many as 50% to 60% of patients with glaucoma have symptoms of OSD,14,15 which can be aggravated by topical IOP-lowering medical therapy.16 Given the favorable safety profile of MIGS compared with those of traditional filtration procedures,3 some patients with OSD may benefit from early MIGS to reduce or eliminate the topical medication burden that may aggravate their OSD.

Table 1. Current State of MIGS3–10 |

||||||

Site of Bypass (Type of Procedure) |

Device |

Maker |

Approved in the United States |

Standalone |

Approach |

Filtration |

| Schlemm canal (internal MIGS) | Trabectome ab interno trabeculotomy3 |

NeoMedix Corporation |

Yes | Yes | Interno |

Interno |

| iStent trabecular microbypass stent3 |

Glaukos Corporation | Yes | No* | Interno |

Interno | |

| Hydrus microstent3 |

Ivantis Inc |

No* | No | Interno |

Interno |

|

| Kahook Dual Blade goniotomy4 |

New World Medical, Inc |

Yes | Yes | Interno |

Interno |

|

| Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy3 |

Ellex |

Yes | Yes | Interno |

Interno |

|

| Ab interno canaloplasty5 |

Ellex |

Yes | Yes | Interno |

Interno |

|

| VISCO360 viscosurgical system6 |

Sight Sciences |

No* | Yes | Interno | Interno |

|

| Suprachoroidal space (internal MIGS) | CyPass microstent3 |

Alcon |

Yes | No | Interno |

Interno |

| iStent Supra suprachoroidal microbypass stent7 |

Glaukos Corporation |

No* | No* | Interno |

Interno |

|

| Gold shunt5 |

SOLX, Inc |

No* | No* | Externo | Interno |

|

| Subconjunctival space (external MIGS) | EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device8 |

Alcon |

Yes | Yes | Externo | Externo |

| XEN Gel Stent9 |

Allergan |

Yes | Yes | Interno | Externo |

|

| MicroShunt glaucoma drainage system10 |

Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd | No* | Yes | Externo | Externo | |

| Abbreviation: MIGS, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery.

* Approved for use in Europe |

||||||

Dr Panarelli: MIGS procedures share 4 common characteristics. (1) They are able to be performed through a microincisional approach (usually a clear corneal incision or a small scleral incision), with minimal trauma to the targeted tissue. (2) As many clinical studies have demonstrated, they achieve a reasonable degree of efficacy. (3) Rapid recovery is typical and is characteristic of their minimally invasive nature. (4) Finally, as mentioned previously, MIGS procedures tend to have a favorable safety profile compared with traditional incisional procedures.3

"As we have moved through the MIGS era, we have learned that IOP reduction comparable to that of trabeculectomy and tube-shunt procedures cannot be achieved reliably without the formation of a bleb." – Joseph F. Panarelli, MD |

In terms of the site of action, MIGS procedures fall into 3 broad categories (Table 1).3–10 The first group bypasses the juxtacanalicular trabecular meshwork, which represents the site of greatest resistance to aqueous humor outflow and provides access to Schlemm canal. This includes the iStent,3 Trabectome,3 Kahook Dual Blade,4 gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy,3 and ab interno canaloplasty,5 all of which are approved for use in the United States. The second group shunts aqueous humor from the anterior chamber into the suprachoroidal space, which can be accomplished in the United States with the CyPass device.3 The third and newest group brings us full circle, returning to the creation of subconjunctival filtering blebs. This group includes the XEN Gel Stent,9 which is approved in the United States and is implanted through an ab interno approach; and the MicroShunt glaucoma drainage system,10 which is approved in Europe and is currently under consideration for approval in the United States and is implanted via an ab externo approach. Early in the development of MIGS procedures, these last 2 devices might not have been considered in the MIGS class because the initial goal of MIGS was to avoid blebs and their attendant complications, such as bleb leaks, hypotony, flat anterior chambers, choroidal effusions, blebitis, and endophthalmitis, but as we have moved through the MIGS era, we have learned that IOP reduction comparable to that of trabeculectomy and tube-shunt procedures cannot be achieved reliably without the formation of a bleb.17 These 2 bleb-based MIGS devices represent safer versions of subconjunctival drainage procedures.3

|

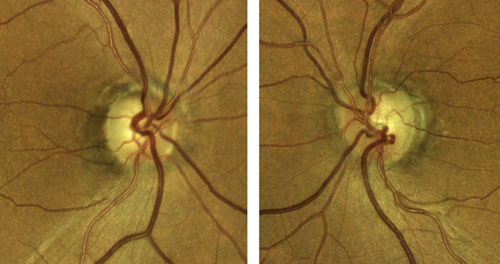

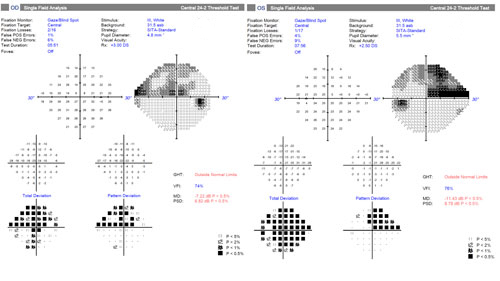

| Figure 1. Right and left eyes of the patient presented in Case 1. Click image to enlarge. |

Case 1. Cataracts and Early Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Well Controlled on 1 Medication

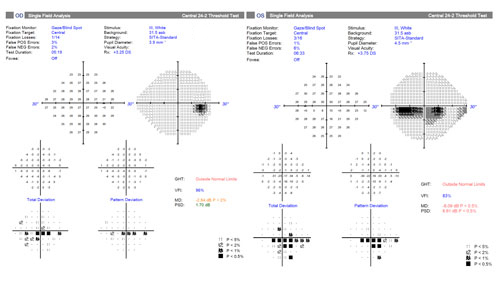

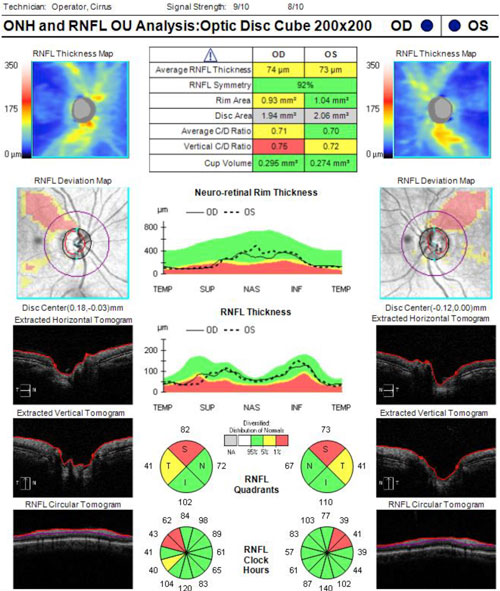

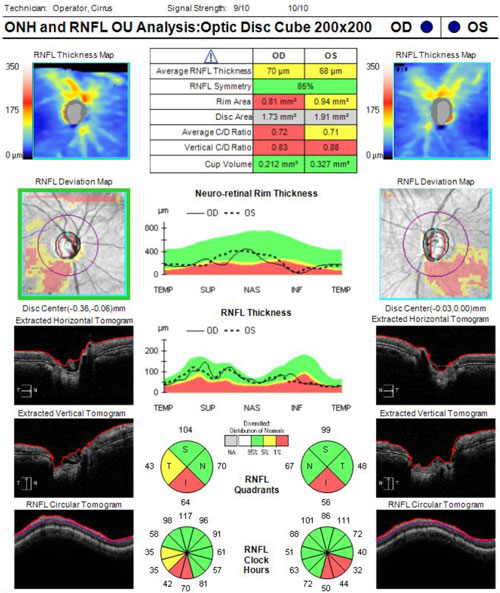

A 68-year-old female is scheduled for elective cataract surgery. Her best corrected visual acuity is 20/40 in both eyes. She also has a 4-year history of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). At diagnosis, her IOP was 25 mm Hg in both eyes. Since diagnosis, she has been well controlled with a topical prostaglandin analogue, with IOP in the range of 16 to 18 mm Hg. Her corneas are of normal thickness. She has early POAG, with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.7 OU with thinning superotemporally OU (Figure 1) and inferior defects in each eye (Figure 2). Optical coherence tomography imaging of the retinal nerve fiber layer (Figure 3) reveals thinning superotemporally in both eyes, consistent with the visual fields. These have remained stable since initiation of treatment at the time of diagnosis 4 years ago.

Dr Fingeret: This case is a perfect example of the way in which MIGS has changed the indications for glaucoma surgery. If we were limited to a trabeculectomy or tube-shunt surgery, I suspect most of us would not consider offering combined cataract and glaucoma surgery to assist this patient in reducing—or, in this case, potentially eliminating—her medication burden. With traditional filtration surgery, the relatively small benefit of easing her medication burden would not be outweighed by the potential risks associated with surgery. In the MIGS era, however, we have safer procedures that can result in the IOP reduction she needs, without the risk profile of a trabeculectomy. My role as the optometrist referring her to a cataract surgeon is to be aware of this potential benefit so I can refer her to a surgeon whose repertoire includes MIGS.

|

| Figure 2. Visual fields of the patient presented in Case 1. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr Panarelli: This is a patient whose glaucoma is currently well controlled, given her stability, so our primary objective with surgery is to improve her vision. While doing so, we can take advantage of some of these very low-risk MIGS procedures to improve the patient's quality of life by reducing her medication burden. When considering MIGS in this setting, I assess the patient's experience with medications. Are they being tolerated? Is the patient having any issues with therapy? Does the patient have symptomatic OSD? Do I suspect adherence issues? The answers to any of these questions might prompt me to discuss MIGS with the patient. If together we decide to proceed with a combined cataract-MIGS procedure, then we must select a specific MIGS procedure. We have several options that bypass the trabecular meshwork and shunt aqueous into Schlemm canal as well as options that shunt aqueous into the suprachoroidal or subconjunctival spaces.3,8 Each of these procedures has a different efficacy and safety profile. In this case, we have ruled out the traditional bleb-based procedures. I would also rule out the bleb-based MIGS procedures because our goal is to avoid blebs and their possible complications. Of the remaining options, I tend to reserve procedures that require excision of trabecular meshwork—such as the Trabectome3 or Kahook Dual Blade4—for patients who have uncontrolled IOP with a healthy disc, such as those with steroid or uveitic glaucoma or pigmentary or pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. In my opinion, these procedures carry a bit more risk than microstents such as iStent or CyPass, so I prefer to reserve them for patients with uncontrolled IOP who have very early disease. For patients who have early disease and are controlled on medications, such as this patient, I find that the iStent and CyPass have the most favorable balance of efficacy and safety, so I tend to use those devices.

Dr Fingeret: One additional option for this patient might be cataract surgery alone, which has been shown to reduce IOP, at least for a period of time after cataract surgery.18

|

| Figure 3. Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber layer of the patient presented in Case 1. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr Panarelli: This is an excellent point. In a major meta-analysis on this topic, cataract surgery alone lowered IOP by a mean of 12%, 14%, 15%, and 9% at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively, postoperatively, with an approximate reduction in mean medications per eye of 0.6, 0.5, 0.4, and 0.2, respectively, at the same time points.18

"For the patient who has undergone cataract surgery and MIGS, additional issues need to be considered. If a MIGS device was implanted, we need to visualize the device and ensure its proper position. We must also monitor IOP and make sure that it is neither too low nor too high." – Murray Fingeret, OD |

Dr Fingeret: The surgeon has many options to consider. Optometry's role in the care of this patient comes into play both preoperatively, when we make the referral for surgery, and postoperatively, when we comanage the patient after surgery. Most of us are familiar with the issues to be aware of during the postoperative period for cataract surgery. As with all surgery, we monitor the visual acuity and watch for signs of inflammation and infection postoperatively. Inflammation is common and is a normal part of the healing process. Some mild redness of the eye can be expected. Significant redness, pain, or discharge should raise the suspicion of inflammation or infection. For the patient who has undergone cataract surgery and MIGS, additional issues need to be considered. If a MIGS device was implanted, we need to visualize the device and ensure its proper position. We must also monitor IOP and make sure that it is neither too low nor too high. We might wait longer after cataract surgery–MIGS than after cataract surgery alone to prescribe postoperative glasses because the healing process with the dual procedure may take longer. Once the initial healing phase has passed and IOP has stabilized, we then consider whether we can decrease the number of IOP-lowering medications. If we see anything that seems unexpected, we should communicate promptly with the surgeon.

Dr Panarelli: In addition to the familiar issues associated with traditional glaucoma surgeries, each of the types of MIGS procedures has unique complications that we should look for in the postoperative period. A common postoperative issue with iStent is bleeding, which can occur intraoperatively,19 immediately postoperatively,20 or even later in the postoperative course21,22—the latter potentially arising from rubbing of the device against the iris. Seeing bleeding at a time point when we would not typically expect it should prompt an evaluation of the device's position in the eye. This requires good gonioscopy skills. Bleeding is also a concern with the trabecular excisional procedures I mentioned previously.23,24 Intraoperative or immediate postoperative bleeding often arises from blood reflux through Schlemm canal due to depressurization of the eye. We try to minimize this by pressurizing the eye at the end of the operation to prevent blood reflux, so it is not uncommon for IOP to be mildly elevated on the first postoperative day. With the CyPass device, we are shunting aqueous into the suprachoroidal space, which is a new approach to glaucoma surgery.3 Some eyes can develop choroidal effusions, forward movement of the lens, and a resulting myopic shift. In most eyes, the effusions resolve and the refraction returns to baseline, but in a few eyes, the effects can be long-term. The CyPass approach is essentially a cyclodialysis cleft, so we must also be vigilant for spontaneous closure of the cleft through healing, which can produce an abrupt and significant elevation in IOP. Even with gonioscopy, the device may appear to be patent, and a referral back to the surgeon may be warranted. As for the bleb-forming MIGS procedures, we should watch for scarring and bleb failure during the first 3 months, as we do with trabeculectomy. If early failure is seen with any of these procedures, the patient should be promptly referred back to the surgeon because there are maneuvers, such as bleb needling, that can restore function in some cases.

Case 2. Moderate POAG Controlled on 3 Medications and Prior Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty Now Undergoing Cataract Surgery

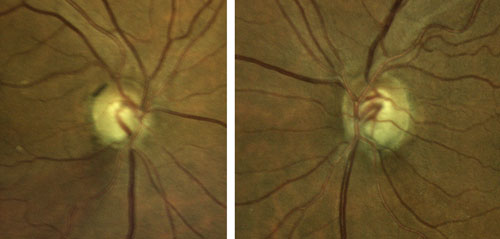

A 70-year-old male is undergoing elective cataract surgery. His best corrected visual acuity is 20/40 in both eyes. He has a history of POAG, which was diagnosed 10 years ago. At the time of diagnosis, his IOP was 25 mm Hg in both eyes and he had moderate optic nerve and visual field changes. He was initially treated with a topical prostaglandin analogue, with reasonable control for several years. More recently, he has required additional medications to control his IOP and has undergone selective laser trabeculoplasty. Using 3 topical medications, his IOP is now 20 mm Hg in both eyes. His optic nerves demonstrate significant cupping with inferior rim erosion (Figure 4). His recent visual field test (Figure 5) and optical coherence tomography results (Figure 6) have been stable.

|

| Figure 4. Optic nerves of the patient presented in Case 2. Click to enlarge. |

Dr Panarelli: This is a case in which the glaucoma, rather than the cataract, is of greater concern to the surgeon. It is reasonable to assume that a patient whose IOP cannot be controlled with 3 medications and selective laser trabeculoplasty may have substantial damage to the trabecular outflow pathway, which may include the distal collector channels, so a meshwork-bypass procedure may not be the best option. In this case, because we need to achieve additional IOP reduction, we may want to consider a suprachoroidal or subconjunctival procedure. The COMPASS trial evaluated the effects on IOP after implanting a CyPass device at the time of cataract surgery in eyes with mild-to-moderate glaucoma.25 In this study, 77% of eyes had a ≥ 20% IOP reduction and up to 85% of patients were medication-free postoperatively. The CyPass device might be a reasonable option for this patient.

Dr Fingeret: An internal drainage device might be reasonable for this patient. Given his need for additional IOP reduction despite 3 medications and laser therapy, he might also be a candidate for one of the newer MIGS procedures with subconjunctival filtration.

Dr Panarelli: Absolutely. We can also consider a bleb-based procedure. This may carry a bit more risk but may be worth it to achieve the necessary target IOP. Our options would be trabeculectomy or the XEN Gel Stent; in the future, we may also have the MicroShunt. The efficacy and safety of trabeculectomy have been well described.11,12 The XEN Gel Stent, which is made from porcine gelatin cross-linked with glutaraldehyde, is 6 mm in length and has a luminal diameter of 45 µm, which is intended to produce enough outflow resistance to prevent hypotony.26 It is inserted through an ab interno approach, which allows the avoidance of conjunctival incisions.

In a phase 3 registration trial, the 12-month success rate (IOP reduced by at least 20%) was 75%.27 The patients in this trial were high risk, considering that approximately 85% had failed prior glaucoma surgery and more than 50% were using 4 or more glaucoma medications. Common complications included hypotony (24.6%) and the need for bleb needling (32.3%).

|

| Figure 5. Visual fields of the patient presented in Case 2. Click to enlarge. |

The MicroShunt is in late-stage clinical development in the United States28 and may be available soon. Similar to the Xen Gel Stent, the MicroShunt device is a tube that connects the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space. The MicroShunt has a length of 8.5 mm and an internal diameter of 70 µm and is made of polystyrene.10 Unlike the Xen Gel Stent, the MicroShunt device is implanted through an ab externo approach and requires a 3 to 4 clock-hour conjunctival peritomy. In a 3-year clinical study of the MicroShunt, the success rate at 1, 2, and 3 years (with success defined as IOP ≤ 14 mm Hg and IOP reduction ≥ 20%) was 100%, 91%, and 95%, respectively, with reductions in medications from a mean of 2.4 preoperatively to 0.3, 0.4, and 0.7 per eye, respectively.10 Common complications were transient hypotony and choroidal effusions, which resolved spontaneously.

"For bleb-based procedures, scarring associated with wound healing can reduce surgical success. Mitomycin C is recommended to modulate wound healing and prevent scarring." – Joseph F. Panarelli, MD |

For both of these bleb-based procedures, scarring associated with wound healing can reduce surgical success. Mitomycin C is recommended to modulate wound healing and prevent scarring for both procedures. Because a peritomy is required for MicroShunt implantation, mitomycin C can be applied by either traditional sponge application intraoperatively or subconjunctival injection preoperatively. With the XEN Gel Stent, mitomycin C can be placed by subconjunctival injection because a peritomy is not needed to implant the device.26

Dr Fingeret: The XEN Gel Stent can be used as either a standalone procedure or in combination with cataract surgery.29-31 The US Food and Drug Administration has not yet established the indications for the MicroShunt, but in an ongoing trial comparing MicroShunt surgery with trabeculectomy, subjects are deemed eligible if their IOP is inadequately controlled on medications alone.28

Dr Panarelli: If both devices were available today, I would say that either would be a reasonable alternative to trabeculectomy in this patient. On the basis of which devices are available now, I think the XEN Gel Stent is an option in this case, and implantation can be performed more quickly than trabeculectomy. The device is minimally traumatic to the eye and requires relatively little postoperative management.

|

| Figure 6. Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber layer of the patient presented in Case 2. Click to enlarge. |

Dr Fingeret: There is 1 additional procedure to consider: a cataract procedure combined with tube-shunt surgery. The landmark Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study demonstrated better outcomes and better safety with tubes than with trabeculectomies in eyes that had prior surgery, either a prior cataract extraction or a prior failed trabeculectomy.11,12 The patient in this case, however, has not had prior surgery. The more recent Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study was a similar trial in surgically naïve eyes and showed that trabeculectomy provided better efficacy than did tube-shunt surgery, albeit with a higher rate of complications, including choroidal effusions, shallow or flat anterior chambers, and wound leaks.32,33

Dr Panarelli: Implantation of the XEN Gel Stent or MicroShunt device is almost a hybrid of trabeculectomy and tube-shunt surgery. The sclerostomy is stented like tube-shunt surgery, but there is no plate and the filtration is into the anterior subconjunctival space as with trabeculectomy.9,10 In this particular case, we need only a modest incremental reduction in IOP and we do not need a very low target IOP; thus, the safety of MIGS is desirable because we do not need the efficacy of a trabeculectomy or tube-shunt surgery.

Dr Fingeret: Postoperative management of XEN Gel Stent and MicroShunt is also more straightforward than that of a trabeculectomy or tube-shunt surgery. This feature will play a role in optometric comanagement.

Dr Panarelli: It is true that we have more options for titrating efficacy with trabeculectomy and tube-shunt surgery. With trabeculectomy, we can vary the size of the sclerostomy and the tightness of the flap sutures and we can cut stitches as necessary. With tube-shunt surgery, we can stent and/or ligate the tube, giving us options for increasing flow postoperatively. With MIGS, there are no manipulations available to titrate efficacy intraoperatively or postoperatively. This is a limitation for the surgeon and patient, but it simplifies the postoperative management considerably. One important issue to consider, especially in optometric comanagement, is the issue of bleb encapsulation, which can occur with both of these bleb-based MIGS procedures just as it does with trabeculectomy.10,26 Should encapsulation occur, referral back to the surgeon for bleb needling can rescue the bleb in many, if not most, cases. In 1 surgical series with the XEN Gel Stent, the needling rate was 43%.26 This is an important point. The optometrist might be tempted to start an aqueous suppressant medication to lower IOP when the bleb begins to encapsulate, but doing so will only restrict flow through the bleb, which might further compromise its function.

Key Take-Home Points

Dr Fingeret: Glaucoma therapy is evolving. We now have procedures that, when performed alone or in combination with cataract surgery, provide new options for IOP control and comprehensive glaucoma management. There are many procedures from which to choose. Factors such as severity of glaucoma, level of IOP and target IOP desired, tolerability of and adherence to medications, and individual patient lifestyle issues will guide the selection of an appropriate procedure on a case-by-case basis. It is incumbent on optometrists to understand the new surgical glaucoma options to facilitate patient counseling, referral to appropriate surgeons, and postoperative comanagement.

Dr Panarelli: This is an exciting time to be an ophthalmic surgeon taking care of patients with glaucoma. The new MIGS procedures offer us so many new opportunities to help patients manage their disease consistent with their individual needs and goals. Because there are so many surgical options, patient selection becomes a critical part of the surgical planning process. Dr Fingeret outlined many of them. In general, MIGS can be described as safer than traditional filtration surgeries at a cost of perhaps a bit of efficacy, so we still need trabeculectomies and tube-shunt surgeries for unstable patients, progressing patients, and those who require a low target IOP. So long as the surgeon and patient recognize that they are trading a bit of efficacy for greater safety, MIGS can greatly affect quality of life.

References

|

1. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Pattern®. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. American Academy of Ophthalmology: San Francisco, CA; 2015. 2. European Glaucoma Society. Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma. Savona, Italy; 2014. 3. Richter GM, Coleman AL. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: current status and future prospects. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:189-206. 4. New World Medical, Inc. Kahook Dual Blade. http://www.newworldmedical.com/product-kdb. Accessed January 31, 2018. 5. Brandão LM, Grieshaber MC. Update on minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) and new implants. J Ophthalmol. 2013;2013:705915. 6. Sight Sciences. Sight Sciences announces CE mark approval for and successful commercial experiences with the VISCOTM360 Viscosurgical System for the surgical treatment of glaucoma. http://sightsciences.com/blog/2016/10/05/sight-sciences-announces-ce-mark-approval-successful-commercial-experiences-visco360-viscosurgical-system-surgical-treatment-glaucoma. Published October 5, 2016. Accessed January 31, 2018. 7. Manasses DT, Au L. The new era of glaucoma micro-stent surgery. Ophthalmol Ther. 2016;5(2):135-146. 8. Kanner EM, Netland PA, Sarkisian SR Jr, Du H. Ex-PRESS miniature glaucoma device implanted under a scleral flap alone or combined with phacoemulsification cataract surgery. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(6):488-491. 9. Sheybani A, Dick HB, Ahmed II. Early clinical results of a novel ab interno gel stent for the surgical treatment of open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(7):e691-e696. 10. Batlle JF, Fantes F, Riss I, et al. Three-year follow-up of a novel aqueous humor MicroShunt. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(2):e58-e65. 11. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL. Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) Study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):789-803.e2. 12. Gedde SJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL, Feuer WJ. Postoperative complications in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) Study during five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):804-814.e1. 13. Tsai JC. A comprehensive perspective on patient adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11)(suppl):S30-S36. 14. Fechtner RD, Godfrey DG, Budenz D, Stewart JA, Stewart WC, Jasek MC. Prevalence of ocular surface complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea. 2010;29(6):618-621. 15. Leung EW, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Prevalence of ocular surface disease in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(5):350-355. 16. Baudouin C, Renard JP, Nordmann JP, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for ocular surface disease among patients treated over the long term for glaucoma or ocular hypertension [published online ahead of print June 11, 2012]. Eur J Ophthalmol. doi:10.5301/ejo.5000181. 17. Chen DZ, Sng CCA. Safety and efficacy of microinvasive glaucoma surgery. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:3182935. 18. Armstrong JJ, Wasiuta T, Kiatos E, Malvankar-Mehta M, Hutnik CML. The effects of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure and topical medication use in patients with glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3-year data. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(6):511-522. 19. Buchacra O, Duch S, Milla E, Stirbu O. One-year analysis of the iStent trabecular microbypass in secondary glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:321-326. 20. Donnenfeld ED, Solomon KD, Voskanyan L, et al. A prospective 3-year follow-up trial of implantation of two trabecular microbypass stents in open-angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2057-2065. 21. Sandhu S, Arora S, Edwards MC. A case of delayed-onset recurrent hyphema after iStent surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51(6):e165-e167. 22. Khouri AS, Megalla MM. Recurrent hyphema following iStent surgery managed by surgical removal. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51(6):e163-e165. 23. Minckler DS, Baerveldt G, Alfaro MR, Francis BA. Clinical results with the Trabectome for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(6):962-967. 24. Greenwood MD, Seibold LK, Radcliffe NM, et al. Goniotomy with a single-use dual blade: short-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43(9):1197-1201. 25. Vold S, Ahmed II, Craven ER, et al; CyPass Study Group. Two-year COMPASS trial results: supraciliary microstenting with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma and cataracts. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(10):2103-2112. 26. Schlenker MB, Gulamhusein H, Conrad-Hengerer I, et al. Efficacy, safety, and risk factors for failure of standalone ab interno gelatin microstent implantation versus standalone trabeculectomy. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1579-1588. 27. Grover DS, Flynn WJ, Bashford KP, et al. Performance and safety of a new ab interno gelatin stent in refractory glaucoma at 12 months. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:25-36. 28. InnFocus Inc. InnFocus MicroShunt Versus Trabeculectomy Study (IMS). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01881425. Updated January 11, 2018. Accessed January 31, 2018. 29. US Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Summary. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; November 16, 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/K161457.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018. 30. Hohberger B, Welge-Lüßen UC, Lämmer R. MIGS: therapeutic success of combined Xen Gel Stent implantation with cataract surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(3):621-625. 31. Mansouri K, Guidotti J, Rao HL, et al. Prospective evaluation of standalone XEN Gel implant and combined phacoemulsification-XEN Gel implant surgery: 1-year results. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(2):140-147. 32. Gedde SJ, Feuer W, Shi W, et al. Treatment outcomes in the Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (PTVT) Study after 1 year of follow-up. Paper presented at: 27th Annual American Glaucoma Society Meeting; March 2-5, 2017; Coronado, CA. 33. Ahmed I, Gedde S, Lim S, et al. Surgical complications in the Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (PTVT) Study during the first year of follow-up. Paper presented at: 27th Annual American Glaucoma Society Meeting; March 2-5, 2017; Coronado, CA. |